Checklist for Determining Movement Dysfunctions: Part 2

In Part One of this series, I discussed how structural and positional issues could result in an impairment to a movement pattern, using a squat as an example. In an ideal world, a “good” squat should be as deep as structurally possible with minimal stress to the individual, essentially letting them hang out with their hamstrings resting on their calves and ribs resting on their thighs,breathing comfortably, and maintainable for a few minutes at a time without much stress. That’s the end goal, but not everyone is meant to get there.

If you can manage the deep squat with a back loaded bar, then more power to you. If you can twerk on command, even better.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1xODURP” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/flE6Zx9qbwA?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=flE6Zx9qbwA&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep5696″ /]

Tony Gentilcore wrote an awesome article on squat mechanics on T-Nation the other day, so check it out for a great refresher on some of the concepts relating to what may cause a structural or soft tissue limitation to the squat movement, outside of what I’ve discussed.

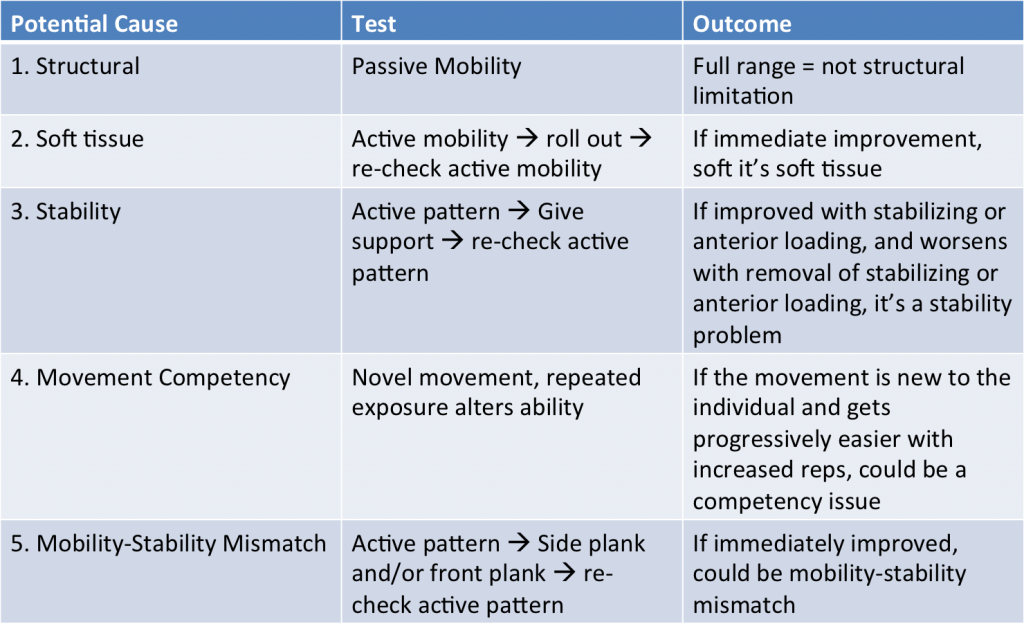

Today’s article will focus on the movement pattern outside of structural issues. We’ll assume the first two tests mentioned in Part One were cleared, and there’s no structural or soft tissue restrictions causing poor depth or movement quality. Consider these steps more of an analysis of the software of the movement program.

#3: Stability

This is a pretty easy one to check and can give you some pretty immediate feedback as to how to proceed. Let’s say someone tries to do a squat free without any support or weight and they wind up barely breaking their knees and quarter squat the hell out of themselves, thinking they’re doing something good. They’d barely be able to sit onto a bar stool, let alone a dining room chair. Let’s say you give them something to hang on to and all of a sudden they drop it like it’s hot with next to no effort.

Going from a 2 point base of support to a 4 point supportive system can help to reduce the amount of force through the legs, which is beneficial if the person isn’t strong through that range of motion, and also help them to balance to find their groove easier than with a smaller base with only two points of contact. Much of it can be psychological, with some people finding new depth with only finger tip pressure on a supportive structure. You’re willing to try something new and difficult if you have a safety net, so providing something to hang on to is a massive benefit.

Another way to check this is to give the person a dumbbell to hold in front of them in a goblet position. This moves more weight in front of their centre of gravity, giving them more leeway to sit back into the movement and find a better point of balance than if they didn’t have it. This is especially valuable for those who feel they have to stretch their arms and shoulders out in front of them like they’re reaching for the last burrito on earth.

[embedplusvideo height=”479″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1xOHED2″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/vG6xU7Hq4JE?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=vG6xU7Hq4JE&width=600&height=479&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep3928″ /]

Front squats work well for this as well, as they also push the centre of mass ahead of the usual spot, allowing for better mechanics for a deep squat to the floor. The downside is they take a lot more in terms of positioning and comfort can be sacrificed if the person isn’t able to get it right, so I wouldn’t use them in an assessment right off the bat.

The funny thing about stability is that the person could have all the mobility, structural accommodations, and strength through the full range of motion, but if they always feel like they’re going to fall over, they won’t ever get to depth. Finding the sense of balance and centration to the movement can be a massive impediment to getting into the movement, and typically can just take altering their centre of mass or through simple practice.

#4: Movement Competency

When people approach any movement, if it’s something they’ve never done before or where they sense a potential danger like falling over, they will automatically tense up more than optimally to do the movement in a guarding or bracing manner. This helps to keep them from being injured while experiencing the movement for the first time, or while going through a new range of motion where they aren’t familiar, but it doesn’t help them to explore the full extent of the movement.

Imagine being a meathead powerlifter and your girlfriend/wife/whomever just said she wants to go dancing and won’t take no for an answer. Doing deadlifts and squat thrusts on the dance floor isn’t a very good option, although there have been crazier dances out there I’m sure. As a result, you get out on the dance floor, sweating profusely from the sheer terror of looking like a complete jack bag and proceed to do some stiff version of a booty shake while Lil John screams in your ear.

Meanwhile there’s a little 80 pound guy with about $30 worth of hair product and body glitter and all the Moves Like Jagger doing spins, jumps, and hip rolls like a god damn reject from Blades of Glory or something making you feel like you haz a sad.

Sure, you could probably out squat the hell out of him, but this is a different movement that he’s probably spent a few hours in front of his tv rehearsing his moves and THIS IS HIS MOMENT!!!!

If I were to try some of those dance moves I’d wind up with a broken leg and single because my wife would literally die from embarassment.

This is all to say that if it’s the first time someone is doing a movement, especially if they think there’s a pass or fail criteria while being observed by a relative stranger, they won’t perform all that well. The novelty of the movement and fear of failure will be too high, so their performance won’t be unrestricted. Sure, they could have all the mobility and strength to do it, but the pattern isn’t there yet.

When we’re young, our body starts laying down motor engrams in our brain that we can call up automatically as we do different things. Think about the kids who grew up in gymnastics and can still do funky things when they’re 30 like front levers and all the Bartendaz moves on playground equipment. Then look at the kids who were in swimming or badminton and can go for ever without getting tired, but who can’t even hope to get into the same positions without falling on their faces. Then look at the kids who played football and hockey and try to help them count to 10.

Most kids in western society don’t spend that much time in a squat position through school, recreation or anything for that matter. As a result, the adults lose the ability to squat at an early age and it becomes increasingly difficult to get it back as they age. If someone is 50 and the last time their calves felt their hamstrings was 40 years ago, odds are they will have some difficulty today getting into a full deep squat while breathing normally and not falling on their butt.

Competency for the movement comes down to how comfortable they are with the position and movement to get into that position. It usually is dictated by a lack of pain, the structure to get there, and the ability to maintain balance without freaking out about it. Also, are they breathing deep and slow or are they looking like they’re about to crunch out a deuce and you’d better give them space? Are they holding their breath and really straining to get it in and out? Probably not a good sign.

If you’ve been fortunate enough to squat deep on a regular basis since you were a kid, you’ve probably maintained that ability. Some cultures use a squat as a resting posture, and it’s beneficial to them since they have the structures and habits to compliment squatting in order to have no problems, even into their golden years.

This is all to say that if you’re used to a movement, you’ll do better than if you’re not used to it. For novices, they’re almost always going to suck, and the more advanced the test the harder it will be to succeed. I don’t use an overhead squat assessment for many people for this very reason: the barrier to success is too high for most of my clients. Sure, I could still use it on everyone, but the end result is I would have to regress each test to find the limiting factors, so I just start with a regressed version which is a body weight squat, and then peel it back from there as needed. If they can hit a bang on perfect body weight squat for depth, sure, I’ll get them to try an overhead version, but if they can’t do a simple bodyweight squat, they definitely won’t be able to do a more advanced overhead squat. That’s like Little Timmy failing on his arithmetic because he can’t figure out why 4 x 5 equals 20, but then asking him to do calculus.

#5: Mobility-Stability Mismatch

Let’s say you have a weak core, or at the very least it’s not “awake” in that it isn’t feeling too strong, reactive or snappy. As a result, your hips wind up getting a little bit more stiff and tight, and they try to create some tension through the fascial networks that envelope the spine. You could try to squat, but the end result won’t be too great. You stretch, roll, and mobilize, but the hips just won’t give.

Maybe try working on some core reactivity to get the hips to loosen up.

If the core muscles become a little more charged up, the hips won’t have to tense up to donate stability to the spine, and they’ll reflexively relax on their own, allowing that range of motion to occur without issue. No stretching, rolling or mobilization required.

I wrote about how core reactivity can impact hip mobility HERE, so check it out to see what I’m talking about.

So here’s how you can determine if it’s a mobility-stability mismatch:

1. Have the person squat and observe it’s overall poopiness

2. Have the person either front plank or side plank

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1xOXeyr” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/it5HKA365gA?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=it5HKA365gA&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep1080″ /]

3. Re-test to see if it improved their squat

4. Fist pump for your success.

If you noticed an immediate improvement in their squat, you have a potential answer, and something you should work into their programming on a regular basis.

So that’s the simple 5-point check list I use to determine the underlying causes of any movement restriction. You can use it for pretty much any movement in the body, and just have to follow the steps. Here it is in a fancy graphic format.

This is a very oversimplified overview of the process of assessing movement, but it’s distilled down to the bare essentials. You can add more if you like, or just stick with this. If you have something that works better for you, give ‘er. This is what I have found to be able to apply to a lot of the people walking through the door without some obvious trauma or pathology, and seems to hold up well across the age spectrum. It goes out the window when the person has had something like a traumatic musculoskeletal injury, sarcoma, or other odd event that makes the body not follow the same rules.

For example, I have one client who had a sarcoma (type of cancer that affects muscle) removed from her thigh, and as a result she doesn’t have a rectus femoris or about half of her vastus lateralis. She has full knee range of motion, decent balance, but has almost no strength in the knee since she’s operating on a half of a VLO and her vastus medialis, which isn’t a strong knee extensor on its’ own. Additionally she has all the scar tissue formation from the trauma of surgery, which is something that foam rolling just isn’t aggressive enough to reduce on its own, and will never actually reduce. For her, these steps don’t work because she’s an abnormality in terms of what could be classified as “normal” movement.

It works for most, but not for all. It still offers a good framework for a lot of people though. Hopefully you enjoy it.

7 Responses to Checklist for Determining Movement Dysfunctions: Part 2