Why We Do Stuff We Know We Shouldn’t, and How It Affects Your Workouts

I’m currently reading a book by Timothy Caufield called “Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything? When Celebrity Culture and Science Clash,” as well as finishing listening to the audiobook by Ori and Rom Brafman titled “Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational Behaviour.” Interestingly enough, they each have a lot in common. Essentially, they both showcase how we use the wrong parts of our brains to make decisions based on certain types of information.

The Caufield book looks specifically at how we form decisions based on the influence of celebrities and how we choose to chase the dream of being rich and famous. It points to things like the beauty industry as a whole, recommendations on blogs and other influencers via celebrities themselves (hence the Gwyneth Paltrow reference) and how incredibly fruitless the search for celebrity is for the very vast majority of people who attempt it.

Sway discusses the specific aspects of decision making processes that cause us to come to some conclusions that can help to form our opinions and actions in the world. For instance, if you bought a stock and it’s value started to drop, would you wait for it to rebound to a specific number before selling to minimize your losses, potentially wait until it was worth absolutely nothing, or have a “bail out” point when you would sell if it ever got that low? What you say now might change if you had the situation in front of you.

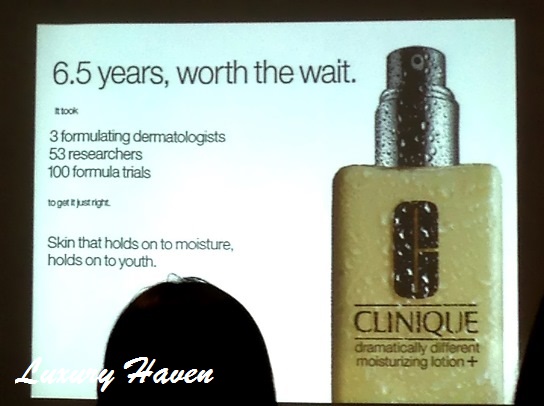

Much of the Caufield book shows how our decisions, if based on the advice of celebrities, will usually not result in any substantial benefits. For instance, he points out that in terms of the beauty industry, there is pretty close to zero dollars spent on researching the products being sold and whether they produce any result at all.

Yep. Zero.

This is a because of a concept known as the Beauty Industry Efficacy Bais, or BIEB as laid out in the book. If you were in an industry all about selling hopes and dreams that using a cream farted from wood elves and pushed through pure diamonds to create a creamy elixir guaranteed to make your skin look like J Lo, complete with an endorsement from her (in spite of the fact that the cream didn’t exist until she promoted it), having research to show that it didn’t actually do what you said it would might throw a wrench in your promotional calendar.

Because of this, we have creams made from avocado oil, bird poop, infant foreskin (seriously, that’s fucked up.), and animals from various animals. Not to mention specific geological species that may or may not have any ability to cross the dermal layer, but that’s just science getting in the way of a good time.

Now as mentioned, none of these products have been specifically studied as to whether they benefit skincare in any way possible. I can only imagine any research institutions ethics boards having a grant proposal come across their collective desks asking to run a study looking into whether smearing infant foreskins across their face made their wrinkles smaller. This study would likely not get any funding at all, especially when compared to something like, oh I don’t know….. cancer.

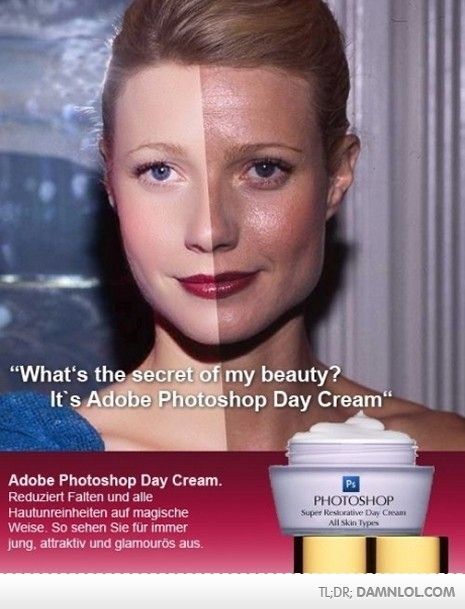

Now while rubbing odd things on your face may sound pretty harmless, the industry has become a multi billion dollar one, and will likely develop into a trillion dollar industry within the decade. This means many many billions of dollars are spent on something with little to no research, based on shaky science, formed on the back of celebrity endorsements (if I use this cream, I’ll look like the 20 year old model in the picture shot with impeccable lighting and photoshop!!), and pushed with qualitative terminology, with words like glow, radiant, healthy, energized, and any other term marketers can come up with that doesn’t give specific outcomes, as that would require supportive documentation to prevent false advertising.

The fitness industry is full of these qualitative and meaningless terms, such as lengthening muscles, toning, elongating (which I guess just means lengthening, but differently), slimming, and any other hard to accurately define term. It’s sort of like saying something is “cool” and then something else tries to do exactly the same thing to be “cool” and fails miserably.

Some of these creams can cost a couple dollars, while others can cost up to thousands, as is the case with Cle de Pau Beaute Synactif Intensive Cream, which goes for $739 per ounce. On this site, a 1.4 ounce container retails for $1000, but if we were to look at the ingredients list, they would be roughly the same and the bottle of Jergens you bought at the local drug store for $4, and would likely be as effective.

Does spending more on cream leave you with better skin, or just a lighter wallet? What has been shown to be beneficial is retinol, filler injections, botox, and sleep. That’s it.

Now if you were to ask someone if they believed these products did what they said they did, most people would say likely not, but they would still buy it. Part of this is for the faint hope that it would work.

Hope is the reason many people do anything without having the odds in their favour. The number of people who try out for any reality talent show and the number who wind up being selected as “successful” is dismally disparate. Hope that each person is “the one” who will make it through and become successful drives them to give up jobs, abandon loved ones, drop out of school, and do everything most people would say are terrible decisions that will likely leave them in ruins, both financially and emotionally.

Hope makes people do strange things. Much stranger things happen in the face of potential dangers.

Think of how many people vociferously oppose vaccinations. These are treatments that prevent significantly dangerous diseases, keep entire populations from being wiped out, and helps millions avoid the unnecessary pain and suffering associated with these diseases. A movement developed, specifically against the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccination, claiming it was the cause of autism, and therefore lead to people choosing to not vaccinate their children. The risk of developing autism, a condition that has never had a single incidence showing any environmental causative factor, and has more to do with genetic maladaptations, was such a convincing fear that people risked their childrens very lives by leaving them exposed to very dangerous diseases.

A recent meta analysis looking at the entire body of research involving vaccinated and unvaccinated children and autism rates showed absolutely no difference in the rate of occurrence and the vaccination state of the child. This didn’t lead to droves of parents rushing to vaccinate their children. Quite the opposite. More parents stopped vaccinating their children, which eventually lead to a well-publicized outbreak of measles at Disneyland right around the time I was in the area teaching a workshop. There was also an outbreak of smallpox too, but whatevs.

For some lighter and probably less hate-mail inducing topic, let’s look at cleanses and detoxes. There’s not much research to show any effect of a cleanse or detox that’s commercially available. The much-maligned “toxins” which are never specifically identified, rarely are needing to be cleansed from the body, and if they are, there are specific organs like your liver, kidneys and skin that do that for you. Plus your colon. It’s great for getting rid of toxins. For many people, a cleanse leads to weight loss. This weight is usually found in the toilet bowl, and through caloric restriction.

In many ways, cleanses work by removing what are known as the Big 8 foods of known allergenic properties. These foods are peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, wheat, soy, fish, and shellfish, although some cleanses allow some of these and others ban other types of food entirely, like fruit or sugar. There’s nothing magical about these cleanses that doing simple caloric restriction couldn’t, and having to take proprietary blend shakes made of doses of laxatives to help speed the process usually doesn’t cleanse anything except your colon, and wallet.

What about sports? If you’ve ever watched or read “Moneyball,” you get a good idea of how decision-making was done before analytical statistics were kept. Some guys were signed because they simply “looked the part” r because they had a hot girlfriend and they exuded confidence. Never mind their on-base percentage was low, or their ERA was very high. If someone can throw in the 90s, they’ll get signed over the guy with a 2.0 ERA, even if he gives up 10 hits a game. He can throw heat, so sign him.

Along these lines, draft picks tend to give some interesting information. First, if you’re not drafted in the first round, you’ll likely never see significant playing time. If you are lucky enough to get drafted in the first round, you’ll see lots of time, even if you suck. Teams don’t want to invest a lot in you and then not have the opportunity to use you. Next, if you are drafted, but never see playing time, you’ll likely never make much money or get much fame. In fact, if you aren’t in the first 2 rounds of the draft in the NFL, your chances of having a career considered anything close to Hall of Fame worthy are almost non-existent.

These aren’t arbitrary decisions. These take lives, millions of dollars, and entire industries into consideration based on what someone decides to do, and where they want to put their interests. In each case, there seems to be a clear-cut winner as to what the best option should be, but we still don’t pick it when we need to.

Let’s take for example, a simple fitness concept that was getting batted around for a long time: butt wink. That little tuck under of some people’s hips at the bottom of a squat movement. Some people said that is was because of tight hamstrings, so the cure for butt wink was stretching your hamstrings. That sounds reasonable, so you spend some dedicated time stretching your hamstrings, and wind up squatting, while still showing a butt wink. You just need to stretch more. You’re obviously not doing enough.

Never mind the fact that the hamstrings actually shorten when the knee is flexed, as it is at the bottom of a squat, or the fact that geometrically the hip socket can limit the flexion angle of the hips in some people, which would limit their squat depth before running into a bony restriction and lead to needing to continue the movement with lumbar flexion (the actual mechanism of the butt wink). When I pointed this out and showed evidence, a lot of people still pointed to hamstrings being the culprit.

Let’s look at the supplement industry. In many ways, this mirrors the beauty industry in promoting broad claims, not giving much research to the ingredients, and preying on people’s willingness to hope for something to be a miracle cure. No supplement manufacturer wants to put in research dollars to show their “proprietary blend” doesn’t do anything but give you some gut rot and expensive pee at the best of times. for clarity, if you ever want to see if a product does have any benefits, look up it’s ingredients on Examine.com and see what they say. They are as impartial as possible, and just give the facts and specific research outlines on what works and what doesn’t, and also how well.

Supplement companies follow the same concept as the beauty industry: qualitative terms (dense, thick, vascular, ripped, etc) which are hard to measure, “celebrity” endorsements from people who won a figure competition and get free supplements to appear dense, thick, vascular and ripped on their advertising, and a GNC salesperson who took a crash course in biochemistry by reading the marketing pamphlet from the company at the last staff meeting.

And people still buy the products, even though many may know that the product probably doesn’t do anything, let alone what it says it does, but there’s the hope that it contains the magic ingredient they want to take their gainz to the next level.

In fact, DNA testing at many supplement lines (specifically natural health and products with specific ingredients listed as the main ingredient) showed that in 79% of supplements analyzed, the product claimed to be the main active ingredient wasn’t actually in the product at all. No word on whether “proprietary blends” are anything at all, or what is actually in those blends.

Some estimates put the supplement industry in the trillions of dollars per year, some in the high billions, which means people are again spending money on nothing, in the hopes they work.

Why?

Why do we do things that we know may not result in good things to happen?

In 2 major outcomes, the answer seems to be hope.

We hope a specific long shot benefit comes to us, even though the odds may be astronomical and almost ensured to not happen.

Additionally, we hope that the risks of our choices are so far removed from us that they would never happen. This explains activities like bungee jumping and how many people choose to drive while under the influence of alcohol.

Let’s look at another choice: The choice to simply exercise. Engaging in an active life, where you do some form of vigorous activity, has been repeatedly shown to benefit almost every single facet of life as we know it, from sleep quality to work performance to appearance, self esteem, and even the likelihood that we’ll develop a serious disease that will make our lives absolutely miserable.

Yet more people are currently sedentary than any other time in history. More people are obese than ever before, and some estimates figure we will be the first generation to have a shorter life expectancy than our ancestors. This is debatable, but is still a consideration.

Why do people choose to not involve in some form of fitness, knowing there is almost no downside to it, if done within the persons comfort and abilities? Additionally, why would someone stop exercising after being involved in the activity for a while, feeling and seeing direct benefits of their actions, and agreeing they were good things? Third, what would prevent someone from re-starting a fitness program, knowing there are so many good benefits, they had previously seen good and directly related results when they exercised before, and saw what happened when they stopped?

When faced with a tough decision, should you take what your head says or what your heart says? Essentially, in any case there should be a couple of things to consider:

- If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

- If the odds of success are extremely small, don’t risk everything to win, especially if a major guiding force is an abundance of luck

- Follow what’s shown to be the most successful. There will likely be the odd case where one person says “this worked for me,” which is cool, but if you see something that has research showing a specific benefit to thousands of people, you should likely look at doing that versus what the one person did. The odds of it working for you will be better.

- When someone says there’s research backing their claims, there’s nothing wrong with asking for a citation. If none can be produced, it’s likely not published, which should be making you a bit skeptical. Published research requires peer review to determine if the methods of the research were good or not, and whether the conclusions were valid.

- If a celebrity is pitching it, their opinion shouldn’t be considered that of an expert. This is how the trend of waist training became a thing after a porn star started talking about it.

So based on this, there are a few recommendations that seem to hold true, no matter who you’re talking to. And none of them are extreme, just effective:

- A basic skin cream will be all that’s needed to moisturize skin. For the best skincare regimen, get lots of sleep, don’t drink much and avoid smoking altogether. Also, wear sunscreen.

- To stay in shape, work out regularly. Do something vigorous on occasion, involving resistance training to keep and build muscle tissue. Cardio exercises help cardiovascular health, and can help burn calories.

- Eat less than you work off to lose weight. Use a combination of exercise and caloric restriction to get the best results.

- Eat slightly more than you work off and resistance train to increase muscle mass. Use compound movements and accessory movements.

- Most supplements aren’t necessary for the majority of people, and usually not in very large quantities. For more information on what works and what doesn’t, check out Examine.com

- Brush your teeth. That’s more for everyone, not just you.

- Work hard, and stay focused on achieving goals.

In the elloquent words of Mike Tyson, “We all do dumb shit when we’re fucked up,” so no one is immune from bad decisions. I’ve admittedly done a cleanse to see what it would do (I developed a very acute bout of immediate urgency to use a toilet, and not much else), expensive face cleansers (wound up getting worse acne), stopped working out for different lengths of time, and played the lotto. The big thing to consider is not trying to avoid doing dumb stuff – because that’s how the best stories come about – but in learning from those decisions and trying to make better decisions in the future.

Decisions based on long shots, fear of failure, or “but what if?” concepts rarely ever work out, so put minimal risk behind those decisions. Hedge your bets with sure things as much as possible, or at least those with more pros than cons and as few risks as possible, and you’ll likely do alright in life. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to achieve the impossible, because even though the odds are long it does happen once in a while where people become amazing. Keep working hard and you might surprise everyone.

One Response to Why We Do Stuff We Know We Shouldn’t, and How It Affects Your Workouts