Butt Wink Is Not About the Hamstrings

Squats are awesome. Whether they’re loaded using a barbell in a back or front squat, with a dumbbell or kettlebell in a goblet squat, or any other variation, they’re a fantastic exercise that can be progressed or regressed nearly infinite different ways to produce different results from maximum strength through explosive power, from mobility to balance and everything in between.

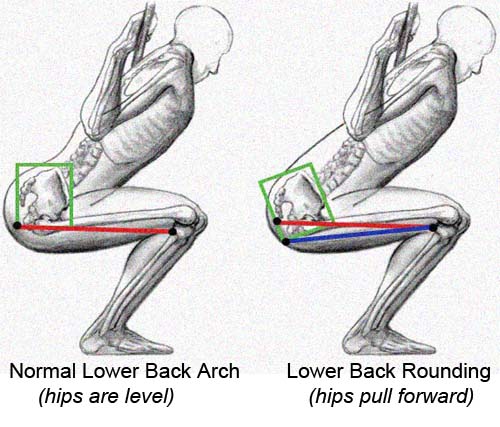

One aspect of the squat that tends to get analyzed to death is the dreaded butt wink. This is when the person gets close to the bottom of their squat and their hips go through a posterior tilt and their tailbone tucks under them, creating a mild flexion in the lumbar spine. Here’s a great example of it from Lee Hayward’s article on the topic.

Here’s an example in a video format.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nu7GkElUryw

To his credit, the person who uploaded the video did mention in the title that there was a butt wink, so I’m not picking on them.

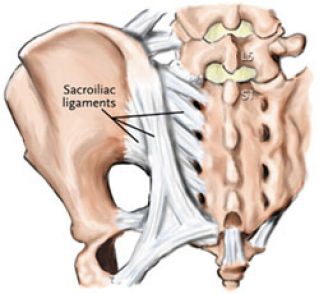

The main issue with a butt wink isn’t the fact that the hips get rolled forward, but that the lumbar spine goes through a extension-flexion-extension cycle with additional load placed on top of it. This is a very common mechanism for disc injuries, and could also lead into some pars articularis fractures if under enough load, and potentially some SI joint issues from the increased stabilization demands of the ligamental support system through the region to try to keep your spine from exploding all over itself. If the demands exceed the ability of the ligaments to manage, you have a very unhappy SI joint.

As a result of this, everyone and their dog on the internet has jumped on the “How to Fix Butt Wink” bandwagon without really understanding why it happens in the first place.

A commonly held belief is that the hamstrings are tight so when you go into the bottom range of a squat they resist letting the pelvis glide back naturally, and as a result wind up pulling it forward as you descend into the movement. The downside to this is that as you squat, your knees bend, which reduces a LOT of the tension on the hamstring and making it so that their effect on the hip in terms of resisting movement is somewhat minimal.

I would argue that the area being stretched would be the glute complex (including piriformis and also adductor magnus). The concept of the knee shortening the hamstrings and the hip lengthening them during a squat is a concept known as Lombards paradox, which states that during a balanced flexion of the knee and hip, no real length change occurs in the hamstrings as well as the rectus femoris.

However, let’s assume the hamstrings are tight and that they could be a culprit. An easy way to test this is to do a simple rock back test while on all fours.

This is a what I call a horizontal squat. If I were to put the soles of my feet flat against a wall, the movement would resemble a squat, including the ankle, knee and hip flexion involved in the decent phase of the movement. The knees would be lined up with the toes, and the hips would be behind the heels. If I were to go through this movement and exhibit no butt wink whatsoever, then it’s not the hamstrings fault that I would show one when I was in standing as the length-tension relationship between the joints and hamstrings would not have been significantly altered between the two positions.

However, what if this movement still produced a butt wink. Would the hamstrings be indicted then? Not likely, as the muscle isn’t under tension as mentioned before, and still there’s some anatomical differences we have to consider as to why the person isn’t able to get into the squat position, regardless of hamstring tension.

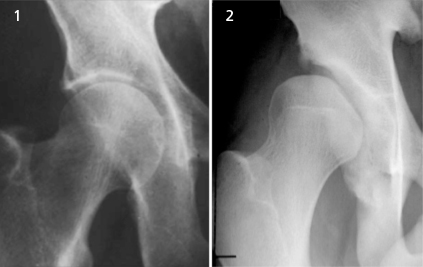

A major factor involved in limiting squat depth before a butt wink occurs is something very few people talk about. Hip socket depth, which is an anatomical variant that can’t be stretched, trained, or undone without surgery, is one of the main biomechanical influencers in how low you can go into a squat before you essentially run out of range of motion and have to find it elsewhere, say from the lumbar spine.

In the image on the left above, the hip socket is very deep, sturdy and likely good for producing power at the very top of the squat pattern, but will wind up creating bone to bone contact much sooner in the bottom range of motion compared to the image on the right, which would have almost no bone to bone contact preventing end range depth.

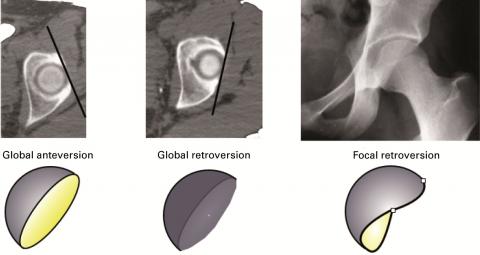

Socket depth is massively important, but additional to this is where the socket is located in relation to the center of the axis of rotation of the pelvis. If the acetabulum (socket’s technical name) is in a forward position (anteversion), it will reduce the chances of bone to bone contact at the bottom of the squat, and also make it harder to get to end range extension past a neutral position. If the acetabulum is in a retroverted position (back of neutral), it will make hitting a deep squat next to impossible without creating some bony contact or tearing through the labrum of the hip, but will help get to extension positions a lot better.

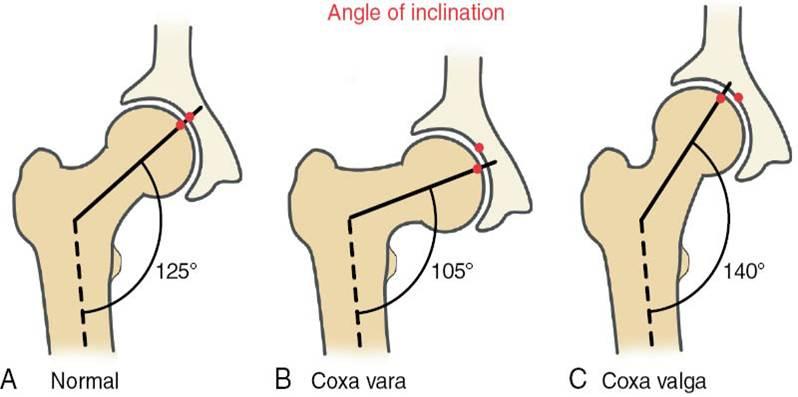

Additionally, if the femoral neck angle is very vertical, there’s going to be an increased chance of bony contact compared to a femoral neck angle that is more horizontal. That said, a vertical neck could theoretically allow for a greater lateral or rotational excursion compared to a lateral angle, which I’ve written about previously on Eric Cressey’s site HERE.

So if you’re one of those lucky bastards who happens to be born with a deep socket, retroverted acetabulum and coxa valga femoral neck, your odds of ever hitting depth without a butt wink are next to none, regardless of how tight your hamstrings are. I could give you a dose of anaesthetic equivalent of what it would take to knock an elephant out for a week, essentially giving you zero hamstring tension and zero tension through any other tissue in your body, and you still wouldn’t have the range of motion to get into a squat. Stretch all you want, it won’t matter.

So back to the original question: how do you fix a butt wink? If the person has no more available range of motion from the hip at the bottom of their squat and their low back starts rounding early, you could try to stretch the hamstrings and see if it makes a difference. If it doesn’t provide a noticeable improvement in your ability to get deeper into the squat, it’s not the solution. If their structure limits further movement, stretching won’t make a lick of difference.

If I use my Checklist for Determining Movement Dysfunctions to solve this problem, so far we’ve looked at whether anatomical issues could prevent the movement from happening with the horizontal squat. If they can hit depth there, it’s not a structural limitation. If we stretch the hamstrings and re-test to show no improvement, it’s not the hamstring tension restricting the movement. Maybe if we did some foam rolling we could resolve that, but if re-testing showed otherwise, it’s not foam rolling.

Maybe they don’t have the stability at that position of their squat? If they only have 2 feet on the ground that’s a much less stable position than hanging from a TRX or handle, and much less stable front to back than if they were to hold a dumbbell in a goblet position and squat to a box. Front squats tend to produce more depth than back squat, possibly because if an easier time finding balance with an anterior load versus a posterior load.

Uh oh. My knees went over my toes on those. I guess my ACLs are going to explode. My bad.

If the movement improves immediately with an external load in the goblet position, it’s not a hamstring issue. Most likely, it’s an anterior-posterior stability issue, also known as balance. Try this out if you’re having trouble getting into your squat:

- hold a dumbbell in a goblet position and squat as low as possible. If you can hit the floor here without issue but squatting without a weight is a problem, this will be a good challenge for you.

- When you get to the bottom of your squat, curl the weight down to the floor and place it on the ground. Slowly let go of the weight and try to not let your spine round or fall over on your butt. Essentially, unload the weight and don’t let your posture or position change.

- Once you’ve let go of the weight and you’re comfortably in the bottom of a squat position, stand up. You just did a squat from full depth.

- Pick the weight up and do it again.

Maybe it’s not a stability issue. Maybe you’ve just never done a squat to that depth before so your body has absolutely no idea of what do do to get there or what to do when it does finally get there, so it avoids it. Movements are just as specific to range of motion as they are to anything else, and if a certain range of motion is novel for a familiar movement, it’s going to be a challenge to get there.

This challenge may require using a supportive aid to get to the bottom of the squat for a few reps, much like using the dumbbell or maybe even hanging from a handle or bar to help you find the bottom, and then standing back up without assistance.

Another option would be to throw down some full depth bear squats to simulate loading through the legs, but with 4 points of contact on the floor versus 2 in a traditional squat.

So because of how many different factors influence a squat and the depth you can achieve, saying you can tell a butt wink is because of tight hamstrings is a massive oversimplification that’s easy enough to refute, but also offers no explanation as to why the hamstrings are tight in the first place either. Are they tight because something in the core and spine isn’t working properly, and if so will stretching the hamstrings do anything beneficial or wind up FUBARing the entire process? Would training the core in a reactive stabilizing manner help with the hamstring tightness, and if so would that then improve the squat? Were the hamstrings really tight in the first place? Do you think that’s air you’re breathing?

Some people just aren’t built to squat to the floor, and that’s fine. Their disadvantage to squatting deep may provide them with an advantage to doing a loaded carry with greater weight and for longer distances, or to sprint, skate, or jump with less effort than someone who can dip it low and pick it up slow. The only people who “need” to fix a butt wink are those who are hell-bent on squatting ass to grass with a load on their back, and for those people there’s very few reasons to do that if their structure doesn’t allow it when they could literally do a thousand different squat variations and other exercises to get similar benefits without risking injury or significant damage.

In which case, they can stretch their hamstrings all day long.

83 Responses to Butt Wink Is Not About the Hamstrings