Want to Do Dips? Check This First

There was a point in time where dips composed a significant portion of my own upper body training program. I managed to get pretty strong with them too, being able to do a set of 8 with 135 lbs hanging off my waist. I don’t know if they were the prettiest reps in the world, but they existed.

After a while, I just rotated them out and forgot to put them back in for about…….. a decade or so.

When I started doing them again, I found that I had a hard time getting stable enough to control where my shoulder was and how the movement was being produced, so I stepped way back to some easier work, and now I can do sets of 12 without much effort again using body weight.

Now one thing to consider when doing dips is the specific range of motion being used during the movement. It’s taking your shoulder through a MASSIVE range into shoulder extension, when the arm is coming behind your back. Because of how big this range of motion is in the movement, it requires you to have not only the available range into that position, but also the control into that position.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons outlines that the average range of true shoulder extension is around 60 degrees, which means before the shoulder blade starts rolling forward off the rib cage or before the humerus starts gliding anteriorly in the glenoid fossa, you’re only able to get to about 60 degrees of motion. Many people will do dips lowering their bodies down to put their shoulders into a position of around 90 degrees, or even more of shoulder extension.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maf8S5R_Gzs

By itself, there’s nothing wrong with going into this range of motion and allowing scapular anterior tilt to occur in order to reach that range of motion. It’s a necessary adaptation to producing strength and power in this position.

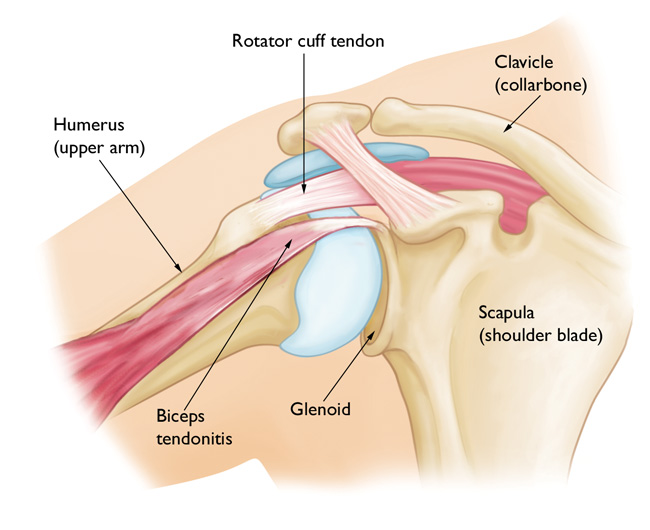

However, where the trouble lies is if this position is uncontrolled, or if there is migration of the humeral head in the socket, as outlined before. That anterior glide of the humerus puts a lot more pressure on the rotator cuff muscles, and also drives friction into the biceps tendon and anterior delt as the humeral head is pressed into the back of the tendon. This friction can cause some fraying, which could lead to bicipetal tendinitis and a world of shoulder crankiness

From this picture, imagine doing some dips, and the humeral head sliding forward into the biceps tendon.

Anterior glide on left, shiny happy shoulder on right.

Bench dips can be even more challenging on the shoulders as your body is in front of the bench, pushing the shoulder deeper into extension. This is compounded even further when you get the person to do the dips with their body about a country mile away from the bench.

So because of how much extension is required in the shoulder to do the movement, it’s important to consider if you have enough of that range of motion to get the benefit of the movement, or if the movement pushes you outside of your controllable ability.

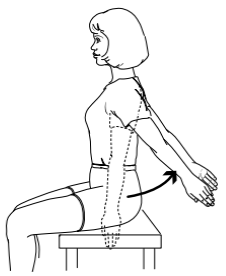

One simple easy way to see if you can get into shoulder extension, as well as pull all the components together that could negatively impact extension (thoracic flexion, scapular retraction), here’s a cool video with a simple stretch to see what you can do.

You could do this with a paralette bar as shown here, or simply grabbing on to your couch or chair at home, or even a bench in the gym. The goal is to see how far you can get into extension without letting your shoulders glide forward, or see what range of motion you can achieve without pain or discomfort.

To be able to do dips well with less risk of anterior glide, you should be able to get your shoulder extension to at least 45 degrees. Remember the average extension capability is up to 60 degrees, so more is better, especially if you’re looking to do some deep dips, or bench dips.

If you can lean into these and get some good range of motion, you’re ahead of the game. Next, let’s see if you can get some control and strength into that position with some light resisted extension work. Don’t sleep on these, they may look simple, but doing them well without jerking the arm around or letting it dive into anterior glide is incredibly challenging.

Depending on body size, if you can lift a 5 or 10 lb dumbbell into 45 degrees of extension, you have the strength to control dips into that position. Think of it this way: you’re planning on lifting your full bodyweight with a dip movement spread between both arms. I’m guessing your body weight that would be held on each arm is somewhere north of 10 lbs, so if you aren’t able to control 10 lbs, how will you control your entire jacked and excellent build all up in here?

From there, can you get into that extension position, and then get OUT of it with some level of control, as in the dip movement?

So to recap, if you can do those 3 simple things (test shoulder extension passively, test it actively with a light load, and then move from extension into flexion), you’re likely able to hit some dips without any real issues. If you can’t do one or more of those things, there’s some increased risk of poor performance, or finding some other way of doing the movement than the way it’s supposed to happen, which means you’re either not getting the benefit of the movement or exposing yourself to increased risk of injury/general sucktitude.

If you find a limitation, and it’s holding you back from doing something you want to do, work on it until it’s no longer a limitation anymore. If your whole existence is tied to your ability to do dips, let’s make sure you’re able to do them well and for decades to come.

One Response to Want to Do Dips? Check This First