The Most Important Low Back Muscle

I’ll be straight forward and let everyone out there in reader-land know I’m not that smart. I’m a simple strength coach and personal trainer working out of a commercial facility. That being said, I do tend to piss excellence when ever I get someone to go through a workout. I can tell if someone is holding their core strong or if it’s flopping around loose as a ham sandwich whenever they try to get jiggy with it in the gym. I’m also smart enough to figure out that if one exercise isn’t working, I’m able to try something else to get the result I want, and help turn meek and mild-mannered Clark Kent types into absolutely stark-raving mad Superhero’s looking to do nothing but throw around more plates than a dishwasher at Denny’s.

Take for example my client James, who is working on getting over a long-standing shoulder irritation injury while simultaneously throwing down a set of 10 reps of 110 pound dumbell goblet squats while making panties drop all across the world.

This isn’t the typical shoulder “rehab”exercise, which all systematically make me want to simultaneously fall asleep, and act like the 14 year old inside everyone who is so that they begin to hop around and do that thing where they swing their arms back and forth like they’re dead and they’re just rotating at their torso, simply for the sole purpose of doing something more exciting than a typical shoulder rehab exercise. Buuuut it works a LOT on shoulder stability, rotator cuff activation, and all sorts of other bags of awesomeness in the pursuit of having James becoming more machine now than man, sort of like Anakin Skywalker, but in real estate instead of as a Jedi warrior.

This isn’t the typical shoulder “rehab”exercise, which all systematically make me want to simultaneously fall asleep, and act like the 14 year old inside everyone who is so that they begin to hop around and do that thing where they swing their arms back and forth like they’re dead and they’re just rotating at their torso, simply for the sole purpose of doing something more exciting than a typical shoulder rehab exercise. Buuuut it works a LOT on shoulder stability, rotator cuff activation, and all sorts of other bags of awesomeness in the pursuit of having James becoming more machine now than man, sort of like Anakin Skywalker, but in real estate instead of as a Jedi warrior.

Now as I’m not that smart, I can’t quite see why so many rehab pro’s are so intense on working with low back pain clients and focusing on small muscles like the multifidus, erector spinae, and the other teeny tiny muscles like that. While I understand the main reasons why they’d be important, from a basic physics perspective, I can’t figure out how muscles with very short moment arms, very thin cross-sectional areas, low thresholds for activation, and minimal ability to both produce or resist spinal movement would be all that important to focus on in isolation, especially at the sacrifice of the big dogs on the block, like the glutes and latissimus dorsi.

I came to the realisation that the big muscles, and one in particular which I’ll get to later, were probably as important if not more important than the inner unit muscles when I was putting together a new tool to work in my yard, and I needed to tighten a screw. The screw driver wasn’t doing the job, so I used a wrench with a longer handle to help generate some torque. I then thought about a time I was using crow bar to do some demolition work for some renovations, and in order to do more work faster and with less effort on my part, I would use a crowbar with a longer handle.

Simply put, the multifidi and erector spinae have very short levers and very small moment arms with respect to leverage being created on the spine in order to help buttress the forces being applied when trying to lift copious amounts of weight, or even for the chicks trying to lift their purse, or to fend off the dreaded sneeze (if you’ve had back pain, you know what I’m talking about here).

Seriously, the muscles along the spine are pretty small and produce such a small effect that they’re almost not even worth discussing when it comes to extension and flexion. McGill found way back in 1991 HERE that the multifidus only really changed its’ length when it was put into a state of near full flexion, which is rarely the position causing low back pain.MacIntosh et al referenced HERE found that the axial torque produced by the multifidus was pretty much non-existed at each spinal segment.

SO why focus on it?? There’s a lot of research that shows down-regulation of the multifidus following any kind of disc injury, and pretty rapid atrophy immediately after any type of joint de-stabilization. We could also make a case to say that the glutes, hip flexors, diaphragm, and any other muscle that associates with the stabilization of the core could be considered dysfunctional in the presence of back pain. For me, when ever my back is not feeling happy, my glutes tense in conjunction with my hip flexors, and I can’t for the life of me get my TvA or rectus to work properly, and I wind up with a bit of a stoop going on.

SO I’ve kept you in suspense long enough while building my case against the common concepts of trying to isolate a small muscle that doesn’t do much for producing or resisting movement, I might as well let you in on my big revelation on the most important low back muscle. And much in the same way Scooby Doo episodes always showed you who the evil guy under the mask would be earlier in the episode (pretty simple to determine,a s you had never seen that person before and all of a sudden WHOOPS there they are), I showed you a little snippet of that muscle earlier in this post. But I’ll tell you again.

The latissimus dorsi is the most important low back muscle.

I’m sure there’s a lot of rehab professionals out there right now trying to throw things at their computer, calling me an idiot, and trying feverishly to unsubscribe from my newsletter in retribution, but before any of that goes down, please hear me out.

The lats, as the kids are calling them these days, attach to the spinous processes from T7-L5, meaning it covers the entire low back and then some. If you also take into account the fact that it blends almost seamlessly with the thoracolumbar and lumbodorsal fascial sheaths, it could even be said to have attachments right to the tailbone through the saccrum.It attaches to the illiac crest, the bottom few ribs, can cause the scapula to depress and rotate by its’ actions on the arm, extend and rotate the thoracic and lumbar spine, scramble eggs, make a mean protein shake, and do the dishes at the end of the day.

They are essentially the longer handle on the crow bar that is your low back. They can generate a hell of a lot more torque and compression compared to the other small deep muscles.

Due to its’ points of attachment on the spinous processes, cross-sectional area, and angle of pennation (what direction it pulls shit), it could be said to have a much larger role in spinal extension than any of the spinal extensor muscles. It’s binding into the low back fascial networks also means it’s integrally attached to core function, due to the fact that the transverse abdominis is also highly involved in those fascial networks.

Now if the lats cause extension and rotation to a greater degree than the multifidus and erector spinae, if they contract to pull the body through these directions, would that also cause the other muscles to fire up and do some work? Sort of like a low back variation of facilitated activation? Damn rights!! I’ve never had a client perform a proper lat activation who said it hurt their back , and never had a client do a proper lat activation who later said they didn’t have a noticeable increase in pain-free range of motion and function. It’s almost a perfect relationship.

When McGill looked at strongman activities like a farmers carry, yoke walk, and log lift, HERE, he found the lats were consistently one of, if not the most powerfully used muscles in each lift, both in single arm and double arm movements. These movements didn’t involve rowing or pulling down or up to a bar, either.

Now I know a lot of people are probably saying “but I do a lot of lat work and it doesn’t help me.” Well, check this short video and let me know if you’re getting yourself into the right position to really feel the muscles working properly.

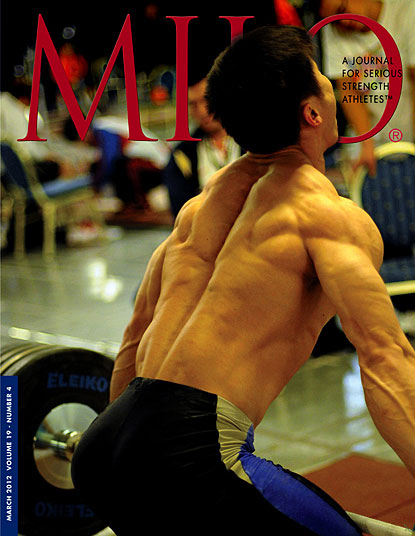

Then tell me if you happen to have a back that looks anything like this guys (pay attention to his lats in his low back).

A common problem with a lot of lat exercises is no one really understands how to make them work properly. People are content to bang out lat pulldowns, chinups, and then the most god-awful creation of all time, the kipping chinup, which turns a lat-based exercise into a flailing excuse for corporal punishment. Much like Bret Contreras is responsible for getting people to re-think glute training, I’m hoping to at least shed some light on lat activation to get the best response possible.

The funny thing is that tying in with “The Glute Guy” is somewhat fortuitous as the lats work best when there is co-contraction with the glutes, and vice versa. The glutes should be fired hard, the back lightly extended, and the shoulders should be drawn back and down towards the back pockets, ensuring you don’t over-extend from the mid or low back, and creating a tense contraction that you can feel all the way from the bottom of your shoulder blades down to your tailbone. You know, because that’s where your lats actually are. I hate it when people say they feel their lats right under their arm pits. and not down their low back, because that means they’re working their teres major instead of their lats.

One of my favorite lat activation exercises is a kneeling pulldown. The seated version doesn’t allow for glute activation and doesn’t encourage a lumbar extension position, which makes kneeling a lot better of an alternative.

I’ve had some really great success working with clients getting lat activation in order to reduce their low back pain, and it also worked very well for myself in my recovery. It’s not typical in most rehab programs to focus on the big units, but I think they should be a major focus in a lot of programs, as the big rocks help to provide a solid foundation for getting stronger and more powerful than by focusing our energy and time on deep and small muscles that may or may not actually have a benefit for the individual getting back in shape faster or in better shape.

Again, I’m not that smart, so maybe I’m completely out to lunch on this, but it’s a theory and I’ll work it for all it’s worth.

44 Responses to The Most Important Low Back Muscle