Are You Ready To Do Stuff? A Post On Mobility

You’ve probably had a few moments in your life where you set the goal of working on improving your mobility. Who knows what sparked it. You saw an ad talking about low back pain and hamstrings somewhere. Maybe an Instagram personality who is bendier than 99.9% of humans and you thought “wow that would be cool.” Maybe you went to put on your shoes and got stuck, or perhaps you had to crawl under the framing of your house Walter White style and found out you’re not as fluid as you thought you were.

These are all fine reasons to want to get more mobile, but the big question you could ask to determine whether you need more mobility is “what kind of stuff do I need to or want to do with that mobility?” It’s one of those nebulus terms that a lot of people would respond to with “well, everything,” but it’s a bit more specific than that. Are you looking to squat below parallel for a powerlifting meet? Maybe you’re looking to hit some high kicks in mixed martial arts? Recover from frozen shoulder? Get off the toilet without rocking back and forth 3 times? Do something like this?

I guess if you want a hip that more resembles a shoulder, that’s cool. Everyone needs hobbies I guess.

Before getting to the mobility plan of all mobility plans (hint, there isn’t one), it’s kind of important to ask what kind of mobility you need. If you’ve never been flexible, or feel like your muscles more closely resemble beef jerky in terms of fluid movement, what would work best for you is somewhat entirely different from the contortionist seen above who obviously has no issues with passive tension holding her back.

Often, those people who have constant tightness and stiffness and move like the Tinman after a rainstorm tend to have a lot of restrictions through soft tissue and capsular restrictions. They may never feel a muscle stretch at end ranges, but are still pretty limited. An example of this is the powerlifter who says they can eventually get to depth, but they need to have 4 wheels a side to help push them down into the hole. These are people who essentially live in 3-ply suits for geared lifting, but exist like this all day long. For those people, my first question is “how do you use a toilet? Like, do you hover, or what?”

Conversely, there’s the people who can move really well through big ranges of motion, but who may not be able to access the entire range available. They can touch their toes, but can’t lift their knee higher than their hip without losing balance or wanting to die a somewhat pitiful death. These two people could use mobility training, but very different mobility.

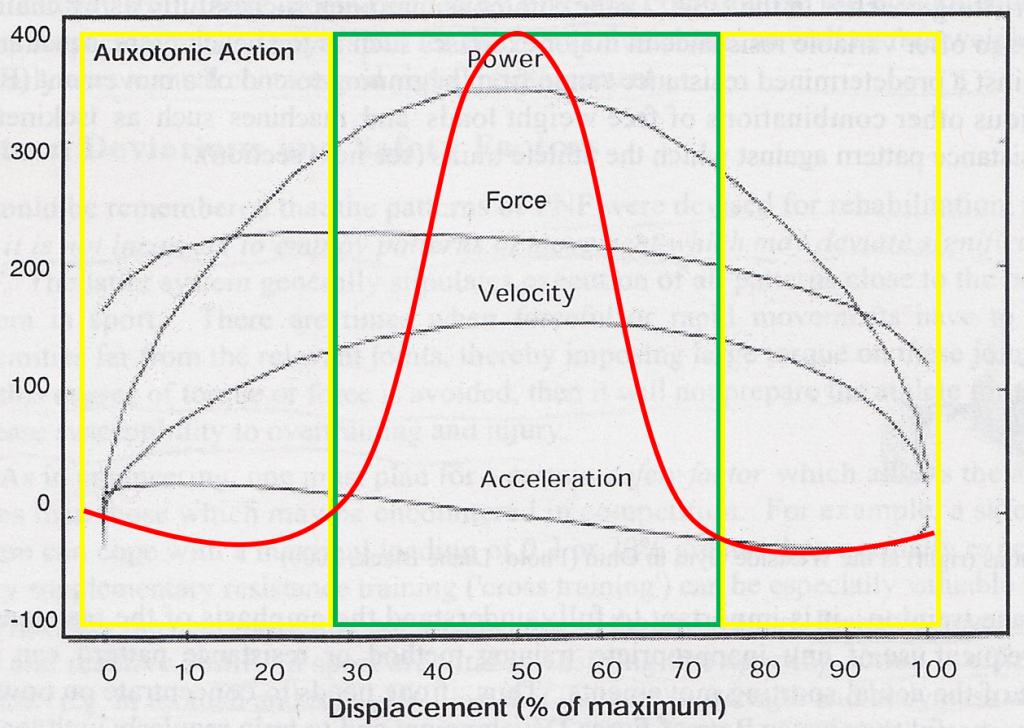

This is the big difference between passive and active mobility. If someone is restricted through a lot of passive means, they likely have either some high resting tension that’s holding them back from accessing bigger ranges or motion, or have structural or tissue maladaptations to getting into those ranges of motion that are keeping them from showing off their best Cirque du Soliel impression. The people who have a massive range of motion available have a lot of passive range of motion, but if they can’t control it in the end ranges or access it effectively, there’s a need for training the active elements. The red line below is where most people tend to exist, whether they have big passive mobility or limited passive.

For the folks who are constantly Tinmen, they seem to benefit most from positional holds, long-term static stretches (more than 5-10 minutes per hold, ideally around 20-30 minutes each), and joint mobilizations with soft tissue work. They don’t have the passive range available, so in order to improve their mobility, we have to take the brakes off and get them to open their available range. If it’s structural, these will affect the tissues like fascia, ligaments, tendons and joint capsules to slooooooowly increase range of motion in that direction. If it’s due to increased neural activity causing muscles to be overactive and restrict motion, it will affect the alpha and gamma neurons that could be causing muscle tension to put the brakes on, so to speak.

For the folks who are bendy and all that, but who can’t get to a position on their own without grabbing and pulling, they benefit from more positional holds at end range, eccentric grooving, ramped tension in those end ranges, and doing less static stretching and more end-range contractions of both agonists and antagonists to help them own those end ranges more effectively. Being able to drop into hip flexion with a squat is one thing, but controlling your positioning and muscle activity in that end range hip flexion is another thing entirely.

So how can you tell which one you need to work on? Consider it this way: if you can pull a joint into position, you aren’t likely the Tinman and don’t need a lot of joint mobilizations or static stretches. If you can pull into that position, but then when you let go you can’t get within a country mile of the same position without everything creating a vacuum of sucktitude, you probably need some work on active control in the end ranges. If you can pull deep and hold deep, you’re good to go.

Here’s a version of the passive test for hip flexion:

Here’s an example of someone with restricted hip flexion post surgery:

And here’s a fantastic example of active hip flexion control at end range from Christine Ruffolo. Check out her Youtube channel for other examples of ridiculous mobility and wicked exercise progressions:

So let’s say you can’t get the passive stretch down. This means you’re going to benefit most from some of the static holds, positional isometrics to alter neural tension through the alpha and gamma neurons, and breathing deeply during everything to affect the sympathetic tone of the tissues being altered.

Another option would be getting someone who knows what they’re doing to hit up some hands-on joint mobilization, soft tissue work, or other stuff to try to coax some motion out of those stuck tissues.

Here’s a bunch of options you could use for the Tinmen stiffness:

For the more mobile but folks who can’t control getting into those end ranges without pulling into them, some of these may benefit you.

For those of you who have the mobility to do what you want, and can control towards the end of those ranges, you don’t really have to do much else, but make sure you’re able to keep control in those ranges so that you can use them when you need them.

The good news is if your joints can’t move to a certain position to execute a specific movement effectively, you’ll find some other joints to pick up the slack. The bad news is if your joints can’t move to a certain position to execute a specific movement effectively, you’ll find some other joints to pick up the slack. Secondary movement compensations can produce problems in those joints that are moving, but aren’t really supposed to for those activities.

If you can’t get the movement from the joints that should do the work, spend time working on them until you can get them to do their jobs properly, then train hard to take advantage of them. If you’re not able to get your arms overhead, don’t try to do it with weight, or handstand, or hang, or fist pump in the club, or anything that would require putting your arm over your head, at least until you’re ready to get there without additional challenges.

Understanding what kind of mobility you need can go a long way to getting more bang for your buck in terms of figuring out what exercises and techniques you should use to improve your range of motion as well as usable range of motion. You can smash, torque, or wrench whatever you want, just make sure the reason you’re doing it makes sense and matches your specific situations.