PRI Integration for Fitness – Another System, Another Useful Tool

Today I have a guest post from Alex Kraszewski, a physical therapist and strength coach in England who not only talks a big game, but can deadlift 3 times his bodyweight. Admittedly, I have not taken any of the PRI modules, so he was kind enough to give a breakdown of what they were, how to use the concepts, and how they could fit into a training program without making the workouts into rehab scenarios without merit.

*****

This past weekend I had the pleasure of attending the first Postural Restoration Institute (PRI): Integration for Fitness & Movement course in the UK at Third Space in London. PRI has become huge in the last few years, and it’s a system I’ve been interested in for some time. With 12 courses on the roster, it might seem intimidating to get started with it. Integration for Fitness & Movement is billed as a great introduction to PRI, without having to choose the red or blue pill and fully going down the rabbit hole. Hopefully – my interpretation below of the material provided can shed some light on this fast-emerging system.

Just a little bit of rabbit hole

What is PRI? A Primer on the Patterned Human Body

Like the Functional Movement System or Functional Range Conditioning, PRI is a system to assess and treat human movement. PRI does not assess nor treat pain, so there is no distinction between what a fitness professional or healthcare provider can ‘do’ with the system. Deal with pain as your scope allows and as always, if in doubt, refer out.

PRI is based on acknowledging that although the body is balanced, it is not anatomically symmetrical in its muscular, neurological , respiratory and vision systems on left & right sides of the body. Particular focus is given to the impact of a larger, more powerful diaphragm on the right side of our body compared to the left. The repetition of contraction of the diaphragm as a respiratory muscle (17-24,000 times per day) creates dominance in certain muscle chains in the body, leading to alterations in pelvic, ribcage and head position to allow us to continue facing forwards.

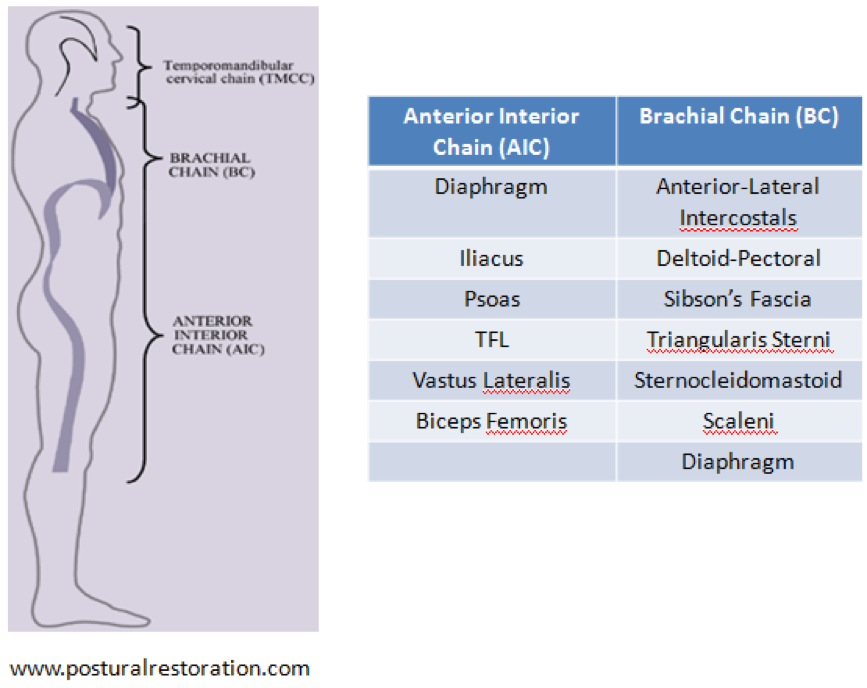

This forms the basis of their two most well-known patterns or presentations; the left anterior interior chain (AIC) and the right brachial chain (BC) – two chains of muscles that become more dominant to their counterparts on the other side of the body. The anterior interior chain includes muscles of the pelvis and lower body, whilst the brachial chain includes muscles of the ribcage and shoulder girdle. The TMCC chain was not discussed on this course.

PRI proposes these anatomical asymmetries, combined with our daily habits, activities and environment in a right-handed lead to right-sided body – with more weight borne on the right and more respiration occurring on the right. The result is a change in body position, commonly a rotation and shift towards the right in the pelvis (Left AIC pattern), and a shift and rotation back to the left in the thorax and ribcage (right BC pattern).

What’s the impact of this?

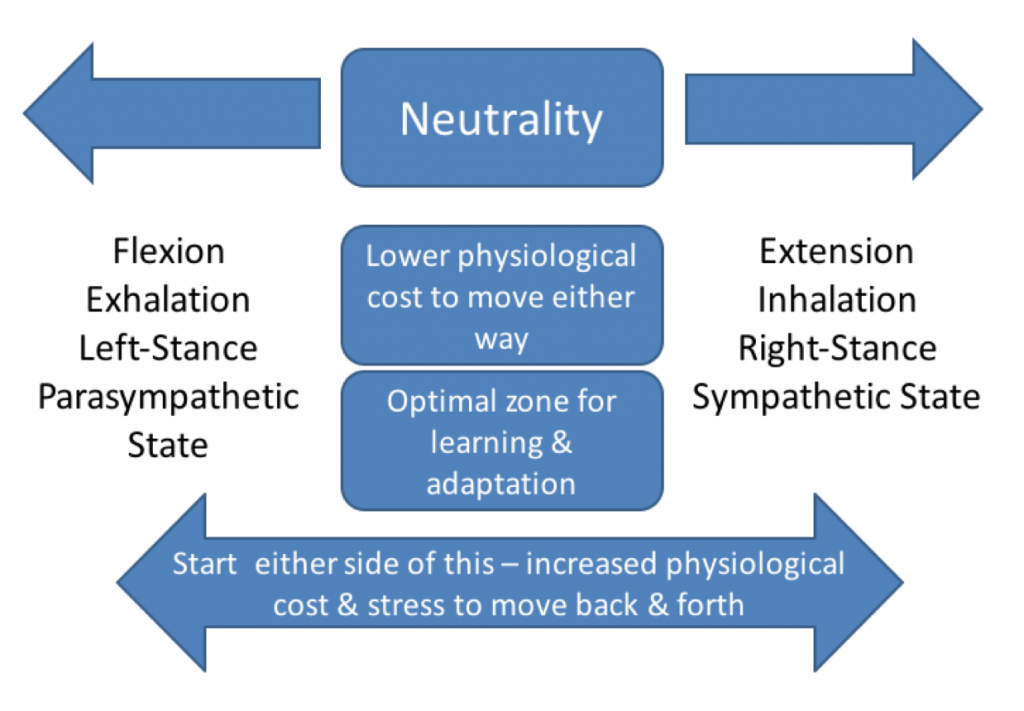

With altered position comes increased difficulty in alternating or reciprocal tasks such as shifting weight from side to side, achieving particular joint ranges of motion, or utilising the full contractile capacity of a muscle. This shifts us from an asymmetrical but balanced state, to an asymmetrical, imbalanced state, away from what PRI terms ‘neutrality’ – a zone where we can shift from one end of a spectrum to the other, and come back again with relative ease. Getting away from neutrality means there is greater physiological ‘cost’ in moving to the other end of the spectrum.

Take a straight leg raise as an example. If your pelvis is positioned in an anterior tilt, the hamstring is already lengthened. When you flex the hip and attempt to lengthen the hamstring further, your range falls short and the hamstring is deemed ‘tight’. It’s not actually tight, it’s just you started 10 yards behind the starting line, whilst a ‘neutral’ pelvis is on the starting line, and gets that extra movement that you lack because of its position. What happens when you sprint on a hamstring that’s starting in a lengthened position? Potentially your injury risk goes up, and you didn’t need to hammer the eccentric training so much, you just needed a better starting position.

You might not need all those nordic hamstring curls after all.

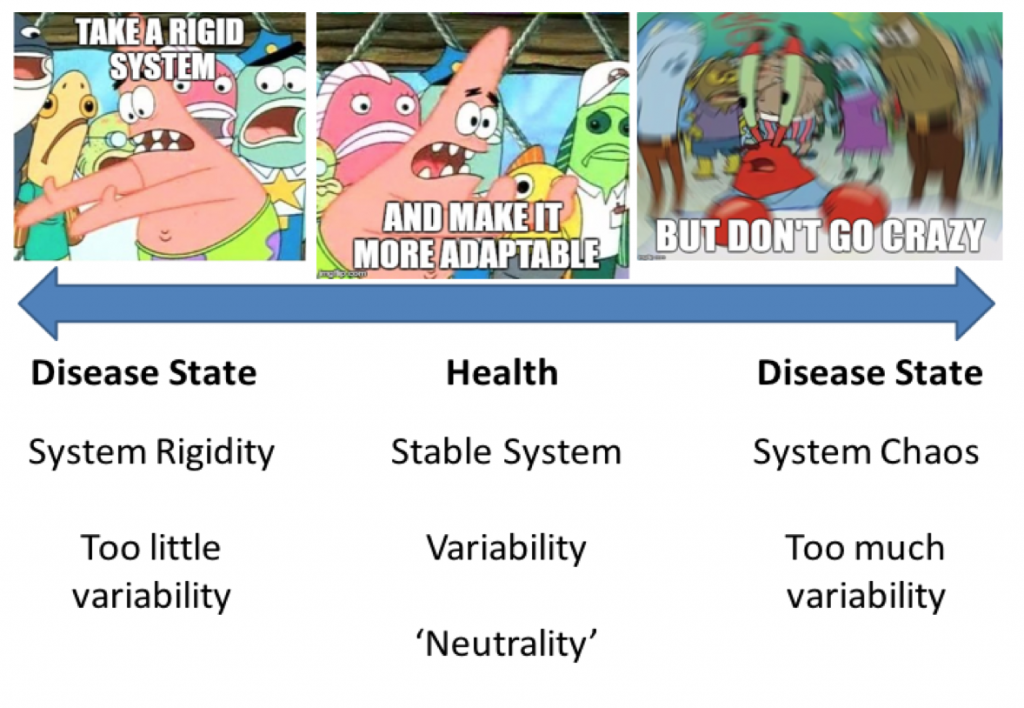

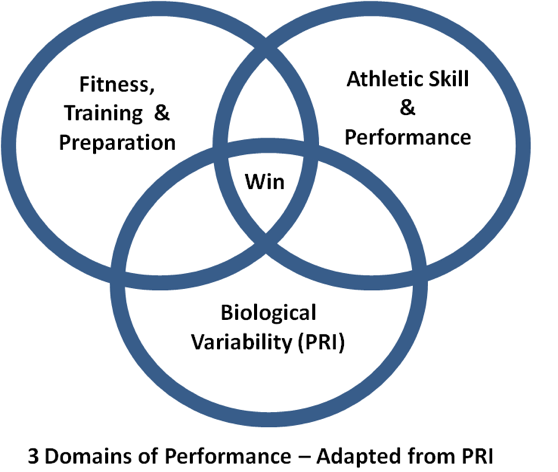

We can extrapolate this to various other systems of the body. Ultimately – the further we are away from ‘neutrality’, the more difficult it is to reach the other end of the spectrum, giving us less variability and adaptability. We know how important variability in exercise is as evidenced by the need for training periodisation and benefits of delayed sports specialisation, but let’s not forget the variability of our own body and biology is just as important.

This concept is not dissimilar from Charlie Weingroff’s core pendulum theory – the closer you live to the middle, the easier it is to deal with stress, and the more durability and longevity you’ll have. Move away from the middle, and your adaptive capacity decreases, and risk of stress, injury or ill-health increases. PRI aims to bring you closer to neutrality by restoring joint position, movement and breathing options to improve system ‘balance’, to make you a more adaptable human being to the variable demands of our training and lives in general.

Variability = Longevity.

PRI: Spongebob edition

What PRI Brings to the Training Table

It assesses & considers the effect of joint position upon movement

PRI uses a combination of traditional orthopaedic tests and a few of its own to test joint position, rather than range of motion. PRI assessments look to establish position to understand it’s effect on movement.

This could be telling you more about pelvic position than hamstring or hip flexor length.

What happens if you don’t adequately consider position in your assessment? Best case scenario – your mobility drills give you no benefit, worst case – you’re hammering on end-range and create pain or instability.

Many of the initial PRI exercises are based around restoring position, rather than actively mobilising a joint or tissue. When you bring a joint or body part closer to mid-range, the range of motion appears greater, but actually you’ve just set the dial to 0, rather than being 20 degrees either side of it, and is why you can see such drastic changes in motion with these repositioning drills.

‘Mobility before Stability’ is well known now – but perhaps it now needs to be ‘Position before Mobility before Stability’. The FMS asks the question; ‘Can the joints get into the right position to absorb & adapt to stress?’, PRI asks; ‘What positions are the joints and system currently in?’

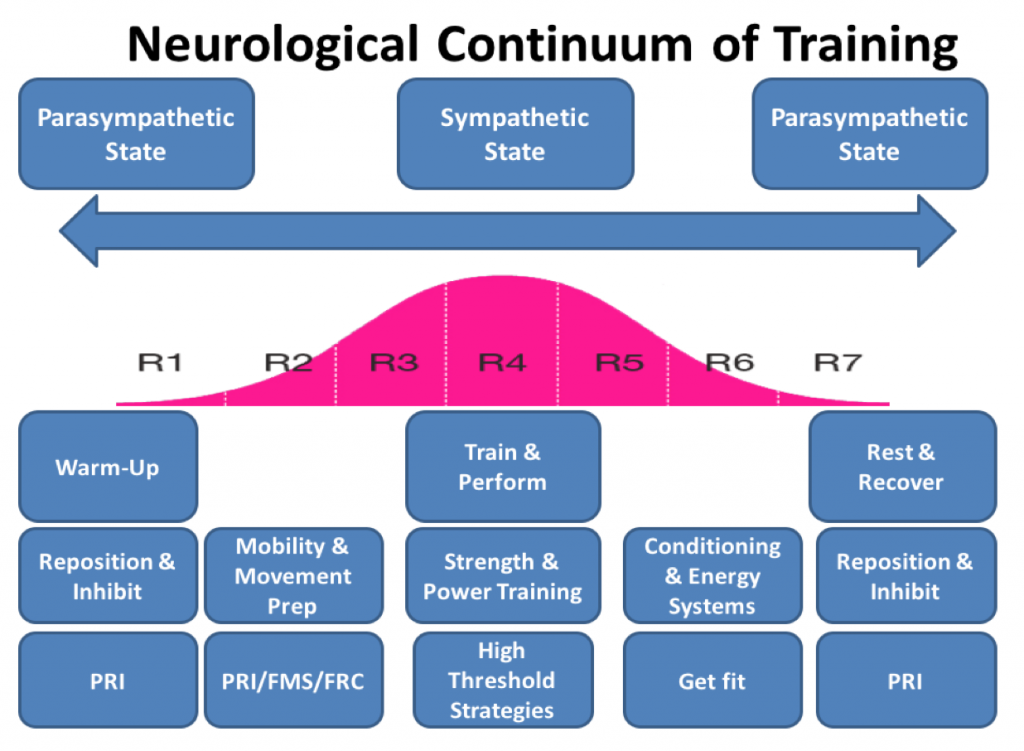

It sits on the Parasympathetic end of the Spectrum

We need high threshold & high tension strategies to perform, but we need to get out of this sympathetic state to relax, recover and adapt as well. Many systems have done a great job of teaching tension, stiffness and explosion, which Dean recently highlighted the importance of it here, but PRI has gone to the other end of the spectrum to help with relaxation. It can be used to get people out of their dominant posture, habits and patterns before exercise to allow effective uptake and learning of the movements and demands of a training session, rather than reinforcing a position that’s potentially limiting performance or contributing to pain.

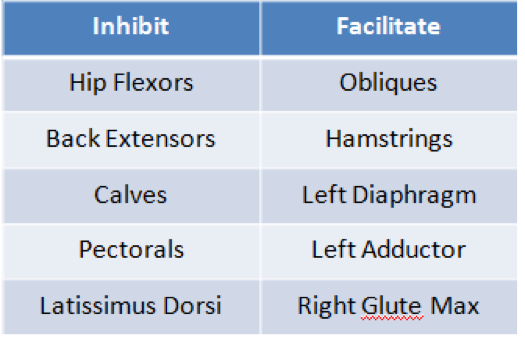

Alongside repositioning, PRI focuses on inhibition – the down-toning of dominant muscle groups and facilitation, the up-toning of non-dominant groups. As PRI becomes more popular – my guess is these inhibition drills will be what self myofascial release techniques are swapped out for. Although each pattern has its own specific targets for inhibition and facilitation, here’s a very basic overview of the big hitters;

Not too dissimilar to Janda’s observations on upper & lower crossed syndromes

Here’s an example. The lats, pecs and low back are placed on slack, and actively breathing helps recruit the obliques and diaphragm for respiration;

PRI isn’t about keeping people in balloon-blowing corrective purgatory with these exercises, James Anderson & Julie Blandin emphasised the need to meet people where they are in their training, and help them from there, rather than turning their world upside down. For most, this will entail some consideration of the warm-up, fillers & active rest as ‘resets’ to help keep someone in a ‘state’ that is more primed for learning and adaptation. PRI is about optimising biological performance, to allow someone to take advantage of the rest of their training program.

Where does it fit in?

I’m looking at PRI as fitting in at both ends of the performance spectrum – as a method of preparation and recovery. It helps tone people down from the stress of daily life, and become more receptive to the demands of a training session – making them more adaptable. Get after like an athlete with your strength & conditioning work, and then get back out of this state into recovery.. Mike Robertson has previously talked about this with his ‘R7’ approach. Below is a breakdown of how this might look with the PRI thrown in the mix;

At a push, you add 5 minutes to either end of the session , but the quality of adaptation you can deliver as a result is money.

Final Thoughts

There was a tonne of information discussed over the two days of this course, but there was a great mix of immediately applicable principles, methods & techniques I’ve been able to use both in the clinic and in the gym already, and plenty to go back and digest in the coming weeks. Special thanks go to Luke Worthington for organising the course – if you’re interested in future PRI courses in the UK, he’s your go-to.

The best systems complement one another, and having taken FRC, FMS and others, this is a great addition to the toolbox and I’d recommend you take the opportunity if you want to delve into the world of PRI. What you get is an overview of the potential it offers with immediate application, without it focusing on a single area too much, as this is the goal for the primary courses where the rabbit hole really starts.

About the Author

Alex Kraszewski is a Physiotherapist working in Chelmsford, Essex, in the UK. Aside from loving Deadlifts, Alex spends his time assessing, treating and rehabilitating clients in the public & private sectors with a focus on resistance training. Alex regularly publishes content on his facebook page – Rehab to Robust.

9 Responses to PRI Integration for Fitness – Another System, Another Useful Tool