Let’s Stop Calling Exercises “Functional,” Shall We?

A massive buzz word in the fitness industry is “functional,” which is touted as being an exercise or type of exercise that is thought to help with completing activities of daily living, or to help improve specific aspects of performance for certain activities like sports and being awesome in general. In many ways this is admirable, as improving your life is sort of one of the main tenets of why many people exercise, but a lot of people tend to take the functional band wagon a little too far and it loses it’s meaning.

The mother-effing MAYO CLINIC even has a definition of what functional fitness is, stating:

Functional fitness exercises train your muscles to work together and prepare them for daily tasks by simulating common movements you might do at home, at work or in sports. While using various muscles in the upper and lower body at the same time, functional fitness exercises also emphasize core stability.

Sounds cool. It gives a big broad grey zone of what could be called functional, doesn’t say certain things aren’t, and says the goal is to get better at stuff as a result of the training.

Now as with anything, a broad definition tends to lead to a large range of interpretation. For instance one could claim standing on an upside down bosu while swinging a cat by the tail and reciting the US Pledge of Allegiance backwards and using the free hand to self-release your contralateral psoas is the BEST way to become better at opening your chi, which is all the rage amongst Kardashians these days so you HAAAAAAVE TO DO IT RIGHT NOW TOO!!!!

The concept behind functional exercises is essentially one used for decades in sports relating to Specific Physical Preparation, or SPP. In this, the goal is to replicate the activities closely, down to speed of movement, confounding variables, and how the athlete feels during the activities, even down to crowd noises. The best example of this would be practice. In football, the players would scrimmage with each other to replicate the game scenario. A baseball pitcher can only simulate pitching by throwing off the mound. We can’t replicate that in the weight room, which would be more General Physical Preparation, or GPP.

For GPP, it’s main emphasis is building the qualities of fitness to better express them when needed. For instance, a football player would do squats to have more leg strength and power when they practice and play, but the guy who can squat the most wouldn’t necessarily be the best player on the team, nor would the guy who squatted the least be the worst. It would just give the player more strength to use when they required it. Anecdotally, some of the guys who have done NHL testing back in the day have shared stories of how the Great One, Wayne Gretzky, had a lot of trouble with the bench press for reps test, but no one really cared as he was winning scoring titles like popping Tic Tacs and winning more cups than a Playa’s Ball.

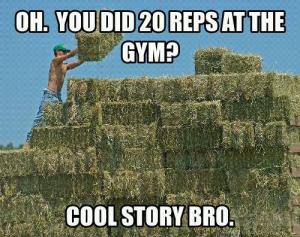

Knowing that to make an activity more SPP than GPP, we would have to replicate the scenarios as closely as possible to what the individual would encounter. For instance, say we have a farmer who has to bale hay and then lift and throw the bales. We would have to have an object roughly the same size, shape, and weight, the grip would be rope ties, and the goal would be to accomplish the act of lifting and throwing the bales effectively and efficiently while reducing the potential risk factors for injury, if possible. And then do that all day during harvest season.

I don’t think this could be replicated in a common gym, unless they’re okay with hay bales everywhere, and knowing most corporate rule structures, they wouldn’t. It’s tough enough to get chalk in most places, but having it look like a barn is going to be a stretch.

As a result, a less specific and more general way of training would be to learn the deadlift, using either a barbell or some odd shaped implement like a sandbag. The barbell would be beneficial for training the muscles involved in the hip hinge and lift, but wouldn’t approximate the position of the bale away from the body or the shape of the handles, or get the benefit from rotation. The sandbag would give a bit more specific approximation to what throwing a bale would be like, but again wouldn’t be as specific as throwing bales. Also, common set and rep schemes would pale in comparison to an 8 hour day in the field, so yet another concept where specificity would be lost. Could you imagine an 8 hour workout involving nothing but deadlifts?

That being said, would the farmer benefit from doing some barbell deadlifts? Absolutely. The strength development would carry over to the ability to throw bales, as general components of fitness apply to a broader development of the individual than specific adaptations. Deadlifting could help someone climb stairs, drive longer with less low back discomfort, look hot naked, and also improve athletic performance, to a certain point. That’s why they’re general: they apply to everything fairly well.

Hockey players tend to do more of their conditioning work on bikes versus running or on rowers, because the strength development and cardiopulmonary benefits seem to be very similar, and in cross-over studies, they seemed to prove more accurate and reliable compared to running, and produced less strain on the joints. For a hockey player, the only “functional” way of training and developing conditioning would be on-ice skating. Barring that, the next best substitute would be cycling. No one would ever say cycling would make you any good at skating if you’ve never touched a set of skates before, so while the characteristics of fitness would be developed, the skill of skating would not.

Sometimes the definitions of functional tend to get confusing as well. One I heard was “developing strength outside of the commonly used ranges of motion, so if you ever wind up in those positions you would have a better chance of knowing how to handle it, recover, and develop power without increasing the risk of injury.”

That sounds good, but if you don’t go into those ranges of motion often, how would that improve your ability to do things within the ranges of motion you tend to exist, and further, would it be necessary to train there if the rarity of the event made being in those ranges of motion themselves, non-functional? In other words, are you preparing for what you do every day, or for what you might do one day without realizing it? To be truly functional, as described in the definition provided by the MF Mayo Clinic above, you would have to limit your training to only what you did on a daily basis, in the manner of which you did it, and within the confines of the ranges of motion, speeds, and loads being used for those activities. In other words, being as specific as possible.

Based on those limitations, anything we do in a gym would therefore be considered NON-functional, or at the very least non-specific or only mildly specific. Gym equipment is often unique to only the gym, and using it is meant to develop aptitude for the body to use the equipment, and then assumes a transfer over to the specific activities. They cannot by nature of their design replicate anything other than their own specific activities, ranges of motion, and patterns of application, no matter how much we try to get closer to the goal actions, so therefore we can only say that anything done within a gym setting is GPP, and not “functional.”

It’s rare you would ever repetitiously swing a heavy object without trying to get it to end up somewhere else, rotate with a foam rubber weight, have your feet in straps and your hands on the ground, or do reps with an unstable load that wasn’t being purposefully replaced in another location. The dynamic nature of sport means sets and reps are non-specific, not even coming close to replicating what would be seen in play. Most daily activities aren’t done in an anaerobic environment, except momentarily and dependent on the individual’s occupation.

Specific? No. Functional? Maybe. Beneficial? Absolutely.

I don’t want anyone to think that I’m harping on fitness as being non-beneficial, as it’s been repeatedly shown to impart strong benefits to the individual doing it, and across a broad range of categories. I’m just pointing out the logical inconsistencies with a buzz word used in the industry that can likely lead to a lot of confusion in the end-user who is trying to get the most from their exercises and the time they spend exercising.

So how can you make fitness develop more carry over between what we can do in the gym and what we would see in the real world? In many ways, the development of general fitness should be foundational. Learning how to develop control through basic patterns like a hip hinge, squat, push, pull, lunge, and learning how to brace and release the bracing effectively can transfer over to a wide variety of activities not isolated to the gym. Using exercises with some variety to them while still training those common patterns helps expand the individuals application of those patterns, and train the muscles, nervous system, and connective tissues to develop force and mitigate force in a better manner, regardless of the patterns used.

Each of the above deadlifts had the same movement, but different positions of load, balance points, goal outcomes and focuses, but were essentially all derivatives of the same movement.

Following this concept, the position in the range of motion where a joint is producing or exposed to the greatest amount of torque would be different in different exercises all doing the same movement. For instance, a deadlift, glute ham raise, and good morning would all produce hip extension in a similar manner, but have different positions where they experienced peak torque, which is essentially where the line of force (in this case gravity) approaches 90 degrees to the hip joint. For the good morning, the greatest torque would be when the individual is bent over to parallel with the floor, and minimal when they stand up tall. This is different than a flexed muscle, which will usually always have it’s hardest contraction at the full extension. For a glute ham raise, they would likely have the greatest torque when at full extension and least at the bottom of the movement.

In many ways, functional training can’t be specific, but varieties of general. For a football linemen, a bench press may not be as highly specific way of training upper body strength to push someone on the line as would a sled push, but it would still develop strength, thickness, and bracing potential that could be highly effective on the field.

So to summarize, “Functional Training” is often a buzz word used to mean something specific, even though the means tend to be more general. For something to truly be functional, it has to have a very high degree of specificity, which can’t be easily achieved in the gym. General training and with a variety of exercises and movements can produce a much better functional outcome than any exercise that tries to be specific ever could, and usually develops better athletes and more robust individuals anyway, so using terms like functional may only confuse the end user as to what is going on versus helping them get the results they want in a way that feels approachable and acceptable. Maybe we should refer to it as foundational training instead, as that’s more concrete. See what I did there?

The last thing I would want is to make exercise more complicated for someone by using terms that don’t approximate what the end goals actually are, and where they can easily see the benefits of the exercise.

Let me know what you think in the comments below. Was I on point, off base, or out to lunch?

2 Responses to Let’s Stop Calling Exercises “Functional,” Shall We?