How the Heck DO You Foam Roll?

Just when I thought it was safe to go back to the gym and look around without wanting to gouge my eyes out in sheer frustration, I saw this one guy trying his best to foam roll on Friday afternoon.

On most days, I’m pretty proud of my big-box gym that I spend 80% of my waking hours within. We have members who do more front squats than back squats, they have a basic understanding of how to do a kettlebell swing that doesn’t look like a hip driven front delt raise, and are willing to do deadlifts for heavy singles or doubles. Sure, some tend to gravitate towardss the adductor machine, but if they can explain why they’re doing a max effort day trying to get their groin a poppin, who am I to judge?

We even have some great trainers who take time to continue to educate themselves, put best practices into play, and try to get their clients the best results possible while keeping them as injury free as possible.

But every now and then someone comes along who makes the day a little more interesting, a little brighter and more memorable, and somewhat fun. We have those oddballs who come through for a workout or two, do some stiff-leg good mornings in the hack squat machine, throw down some pelvic anarchy in front of every mirror in the free weight area, and essentially go out of their way to prove theories of gravity completely incorrect. This guy wasn’t to that extent, and to his credit he was just a little off the mark instead of a complete train wreck.

Now I can assure you he had the best of intentions, I mean he’d actually taken the time to roll out before starting his workout, which means he has at least dial-up access to the interwebz. Maybe he even read a book or two, had someone take him through foam rolling, or something like that. The point is, he had SOME experience with foam rolling.

What stood out was the fact that he was rolling out his IT band at a speed that could be best described as rocket-powered. He went from toe to hip and back again so fast I thought he was trying to start a fire. If he had a dead wildebeest beside him and was looking kinda hungry, it would have been the best explanation. Seriously he was ripping into that thing like a rocket-powered sled, which is an awesome concept but not likely to result in my mom staying inside the house and not screaming at me from the back yard that I was going to break my neck.

Maybe he thought the faster he went the more friction he would create in the tissue and cause some “warm-up” concept similar to the old guys who sit in the sauna and start sweating and call it a warm up. “Hey, I’m warm. That’s the same, right?” Umm, no.

Now while going at the speed of sound won’t necessarily cause any negative issues while foam rolling (that is unless you rip a rotator cuff trying to stop your roll or maybe bruise a bony end whacking into it at high speed), it also won’t do you any favours to help get you the best results.

A lot of people tend to roll way too fast, which may come down to a lack of technical articles available on how to roll properly, a small amount of research available on the topic, and a general mis-understanding of what fascia is and can do. I mean, up until about 20 years ago, back surgeons used to cut out portions of the lumbodorsal fascia and throw it out, saying it was getting in their way and limited their ability to do a proper disc surgery. They also used to cut through the transverse abdominis, saying it was a fairly useless muscle. I know this because a back surgeon did this to my dad.

An article came out a few months ago that was a great rant on how foam rolling isn’t causing any change in length of the tissue, and while I agree with a lot of points he made, there were some that were contentious. Along the same lines, Jon Erik Kawamoto did a great meta analysis of the research available on foam rolling in this post, and showed some of the big findings, such as no reliable change in muscle length, no reliable change in performance, and a complete lack of ability to fight crime or drive super-fast cars while looking like Daniel Craig in Sky Fall.

What Does Fascia Do??

Everyone has a different opinion on what fascia does. Some people say it’s the connective tissue that holds everything together, some say it’s secondary contractile tissue, others say it’s an extension of a sensory organ, some say it’s where your spidey sense originates and since we only use 10% of our brains we have yet to gain this super power.

While we don’t know a lot about fascia, we know a few key things:

- It’s everywhere. It wraps around and throughout muscles, creating interconnections between muscles and other tissues.

- It has smooth muscles embedded in the matrix, meaning it has an involuntary contraction capacity

- It has more sensory receptors per cubic centimeter than our skin. It relays pressure, tension, compression, shear force, and reflexive alterations, plus is really sensitive to dehydration.

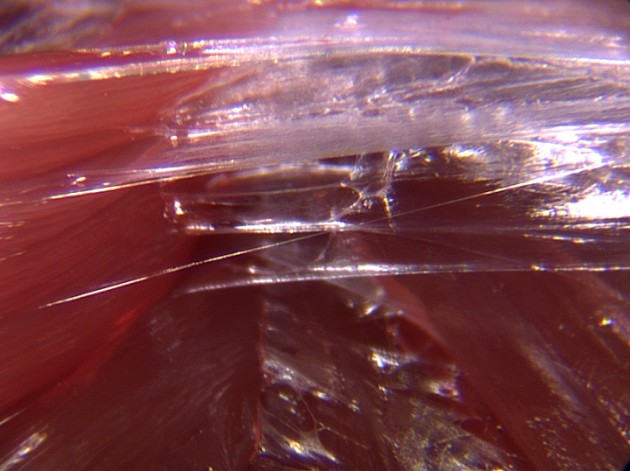

- It looks pimpin under a microscope.

Fascia has around 16 different types of receptors throughout its matrix, which helps it detect changes in a bunch of different things like hydration, temperature, pressure and tension. Two such receptors, Ruffini fibers and pacini corpuscles, are really important to working out and foam rolling in particular. Ruffini fibers sense pressure changes within the tissue that would lead to damage and have a gradual relaxation potential, whereas pacini fibers do the exact opposite, sensing high degrees of stretch and slowly create action potentials to get muscle contractions.

This is similar to two receptor types in the muscles that we view way back in beginner muscle physiology: the golgi tendon organ and the muscle spindle. Gogli tendon organs sense crazy high tension and shut the muscle down so it doesn’t rip itself apart. We see this when someone is doing a bench press, gets it off their chest, presses into an unchanging bar position, then has the muscle pretty well shut off. The GTO is like the emergency shut off switch.

The muscle spindle senses rapid length changes and causes the muscle to contract so it doesn’t get pulled apart. The classic example is the doctor testing your reflexes by using a little rubber hammer and hitting your patellar tendon, causing a rapid stretch reflex through the quad muscle, and resulting in a small kick. The spindle sensed change, and resulted in a reflex action to prevent damage.

So the muscle spindle and golgi tendon organ cause some really rapid changes in the muscle action when there’s a rapid application of force to them. Let’s call these fast-twitch receptors. The ruffini and pacini receptors do similar things, but they do so in a much more gradual manner. Let’s call these slow-twitch receptors. The benefit of having these slow-twitch receptors is that they’re way more energetically efficient to produce tension around joints and promote stability while not needing the big force producing muscles. You can call up the big boys when you need them and rely on the little guys when you don’t need that much force production.

If you roll very quickly over tissue, the rapid movement will stimulate the fast-twitch fibers, specifically the golgi tendon organ, which will cause the muscle to contract instead of relax. The pacini fibers take a more gradual approach to releasing, and need more time under pressure to get a solid release.

Now as with any receptors, they all tend to work on a threshold concept, which means they have to hit a specific level of stimulation in order to produce an effect. Golgi tendon organs require a pretty good amount of force to see reflexive contractions, whereas ruffini fibers only take a small shift in position to hit threshold. As a result, they also take a much lower level of loading to cause relaxation than the muscle spindle, which tends to take a near injurious level of force to cause a shut down.

The tricky part comes to finding the right zone of pressure so that receptors relax and new ons don’t turn on. We’ve all probably had experience rolling through an area so tight that you felt muscles tense and guard on top to try to reduce the pressure somehow. This contraction means the threshold for the golgi’s was reached, and the pressure is too high.

Simply put, foam rolling shouldn’t hurt.

It should instead be somewhat uncomfortable, but not so painful that it causes co-contraction and guarding from other tissues, or the inability to breathe normally. If you’re clenching down, how the hell is that supposed to be a release in any way, shape or form???

For most beginners, the low density foam rollers are more than adequate to produce this reaction, and as someone gains more experience with rolling they can graduate to the higher density ones, as their ability to reach threshold becomes blunted with long-term rolling. In other words, they start to adapt to their tissues and begin to re-position themselves so they don’t have to continuously load those over-used areas. Same way you can train a muscle or train posture, you can train fascia.

Once you can use things like high density rollers, you can start playing with some of the more S & M types of rollers out on the market. I tend to use a basic roller, a street hockey ball or two, and occasionally some times more advanced tools, but most of the time like everything else, the basics work best.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uoazu3aQC0g’]

For a more intensive rolling session, you could try what Kelly Starrett calls a “tack and stretch” method, which I find really effective for pec minor or subclavian areas.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YYAAE1Cz_IA’]

The key to foam rolling effectively is to go fairly slow, and when an area feels very tense it should be even slower. I’m talking glacial migration patterns slow, like a foot a year kind of thing. The pressure should be enough to make you aware of it, but not so much that you can’t breathe or start bracing against it, which means you have to be fairly judicious in picking your torture device and how you want to use it.

I talk about fascia and rolling a lot in Muscle Imbalances Revealed: Upper Body, and detail ways to roll effectively and what happens when you do it right versus when you become a walking basket of fail.

Additionally, I’m teaching a workshop in Calgary this coming Sunday on foam rolling science, application, and technique, so if you want to check that out click here to register and get your learn on. You can even get a Travel Roller at a good price too.

17 Responses to How the Heck DO You Foam Roll?