Giving Up Doesn’t Make You Weak

The advice medical professionals will give to someone who is suffering from any overuse injury is to avoid the activity or movement that causes the pain or discomfort. The old quack addage of “Doc, it hurts when I do this,” “Well then don’t do that” is actually founded in a fair bit of science in terms of the healing opportunity of tissues, the sensitization of repeated irritation, and the decreased strength and positive active remodelling of tissues following damage, but it sounds pretty dumb in most cases.

While prudent, it usually doesn’t go over well in the eyes of the person who is there to get help. They’re expecting some treatment, advice on an exercise to do or something that will help end the problem and allow them to continue doing the thing that’s causing the issues they’re facing, in spite of the challenges that may present.

Part of the problem with these injuries is the thought process of the individual who is dealing with them. There are a lot of sports or even simple recreational activities that proudly preach training or playing through the pain as a way of either paying your dues, earning your respect, or becoming a better person as a result of being able to make it through the process.

Ask anyone sitting in a physios’ office if they’re glad they pushed through the pain. They usually aren’t.

This isn’t only something that’s done by people getting injured. It’s something I see all the time with people doing the same programs or chasing the same goals, even though their progress has either stalled, reversed, or the thought of progress itself is just plain laughing in their face at their attempts.

My good friend Sol Orwell wrote an awesome post on survivorship bias and the lure of gurus the other day, and it was an amazing parallel to what I’m talking about today, so give it a read.

To cogent to todays post, we’re always told the results and gainz we’re after will come if we simply work hard and stay smart, while also believing we can do anything we want. While the idea is noble, it’s not really backed by any information than warm fuzzy hugs and wishful thinking.

There’s a lot of things you can’t do or shouldn’t do. For instance, as a 6’2″ 245 lb human, I’m likely not going to be a jockey, rock climber or Cirque du Soliel contortionist, because the horse would be slow, I’d fall, and likely break my spine, respectively. I’m also relatively weak for my body size, but if I were to ever compete in the 60kg women’s powerlifting category, I’d probably clean it up.

Someone with deep hips and retroverted acetabulums will likely make a poor olympic lifter due to their inability to catch in the lowest squat position and therefore having to pull the weight significantly higher compared to someone with different hip anatomy. Also, tall lifters suck compared to shorter lifters, especially relative to weight classes and lever advantages. Tall, long armed swimmers are faster than shorter and short armed swimmers. Hypermobility lends itself well to gymnastics, but not to marathons. In short, the best secret to seeing the results you want isn’t actually hard work, it’s genetics.

If I take 2 different people of the same age and same relative training experience (let’s say, zero) and assess their squat, and one is the epitome of a rusty hinge while the other drops to the floor in what could be best described as a perfect textbook squat, I can’t look at the rusty hinge dude and say “you just have to work harder, like that person, and you can squat like they can.” Sure, hard work can help see improvements in many cases, however how could I justify saying hard work was the resulting factor that caused the textbook squat if they have never trained a day in their life? There are some advantages you just don’t get from training, and you have to be born with.

That being said, people still have the freedom to try the different sports, knowing they may not be the best in the world at it. That’s all well and good. I train in olympic lifts, some bodyweight calesthenics, and other stuff, knowing that I’m not all that good at any of them. My volume and frequency for these are each relatively low, so if at some point they start disagreeing with me, I can sub them out and not feel heart broken about it.

Part of the benefit for each of these is that my overall investment into each has been fairly minuscule in terms of time and finances, so if I had to give them up, it would be incredibly easy. For someone who may have put significant time, energy, and resources into an activity, giving it up can be incredibly difficult, even if that activity isn’t giving them any positive benefits and is actually causing them more harm than good.

This is known as the fallacy of sunk costs, where the individual justifies (incorrectly) that because they’ve put so much interest into something, they have to keep going with it in the hopes that their fortune turns around.

This is akin to purchasing stock in a company, then watching it’s value tumble week after week and avoiding selling, in an attempt to recoup some of the losses. Maybe if you hang on another couple of weeks, the price will rebound and it will only be a 70% devaluation instead of an 80%. Or maybe it will be one of those rare unicorns that will tank, but then go through some corporate restructuring and miraculously produce a winner.

Or, the fire will just continue to burn until there’s nothing left.

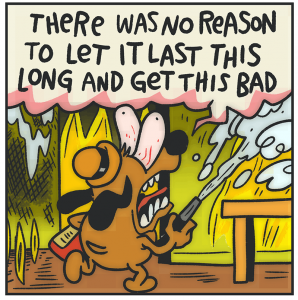

Maybe instead of this, the dog should have been doing something a little different:

But hey, pain is just weakness leaving the body, amiright??

Yes, working hard will produce results, if it’s intelligently applied work and in a direct relationship to the results you’re looking to achieve, and within the balance of recovery and adequate nutrition. Details matter. We know this about training. We know there are physical laws about how tissues will adapt or develop based on the stressors applied. The Law of Repetitive Motion, Wolff’s Law of bone stress adaptation, the Law of Repetitive Motion, Davis’ Law of Force Line Adaptation of Tissues, Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands, the Three Laws of Thermodynamics, Murphy’s Law. I could go on. If you do something to break these laws, bad things will likely happen.

The downside is that understanding how everyone has different anatomical gifts and limitations, as well as the limitations to productive benefits that can come from “working hard,” we still see a opulence of fitness professionals and personalities giving advice that is generalized across the population with some arbitrary pass/fail criteria they feel everyone should be able to hit.

- You should be able to hold a deep squat position for 30 minutes a day to consider yourself healthy

- You should be able to run a 6 minute mile to consider yourself fit

- You should be able to do X feat with Y weight for Z time to qualify for Q exercise

- If you don’t do this thing I’m showing you for the first time, you’re a terrible example of a man/woman/human

In each of these examples, it’s cool if you can do them, and it’s good to try to see how you stack up. If you have the ability to do the thing they’re telling you, and you just need some more exposures to it to achieve the goal, then train hard and smart and work towards it. I did this with the SFG snatch test a few years ago.

When I started, I could only get about 75 in 5 minutes and needed to seriously push my cardio, which improved, and I was able to complete it. Yay me.

However, to say that someone should be able to do these feats, even someone who anatomically could never do them, merely defeats or depresses them for not being able to do it, or puts them in a situation where they want to achieve it come hell or high water and wind up getting beat up in the process.

Now, consider this same goal with someone who has altered shoulder kinematics, or a history of low back pain that wasn’t the same as mine, or maybe it was, and doing this caused them a lot of discomfort and pain, and left them feeling like they were run over by a truck for about a week after each attempt. “Just push through” would not be very prudent advice, nor would “just work harder.”

Now if the completion of this physical test was the determining factor of the individual getting or keeping employment, of course we would do everything possible to complete the test with minimal damage to the individual. If they were an athlete and were paid to play the sport, even though the specific movements or positional requirements were causing trauma, we would absolutely do what was required to help the individual compete while attempting to manage symptoms as best as possible.

If someone was doing this as a fun goal and had nothing on the line for competing or not, I would likely have a discussion about the realities of the stress on their body and whether it was worth it to them. If competing only made them feel warm and fuzzy, but significantly and negatively affected how they were able to work or the time they spent with their family, there are some priorities that are bigger than the potential of a $50 check from a local fun run or cool trophy from a regional weightlifting meet.

If there’s literally nothing on the line other than your sense of self-determination to conquer a goal you set, there should also be no reason to continue with that goal if it’s untenable. You can find other goals to achieve.

Let’s re-frame the concept a little. Let’s say you come out of college and apply for your very first job. You get it, things are happy, you’re getting a paycheck, everything’s golden. A few years go by, and the office politics start to get on your nerves. You start to see things happening that are slowing down progress that could be happening with relative ease, people who are more toxic than beneficial, and you get an idea for how little your contributions are actually valued. You start thinking of finding another job, but decide it’s not too bad and you should stick it out.

A few more years go by, and the slow soul-crushing venture of it all is beginning to weigh you down. You’re in therapy to deal with the issues your job is creating in your life, you haven’t had a raise in ever, and are still making the entry level income from a decade ago while your friends you graduated with are on to their fourth or fifth career and making mad cheddar. Oh well, stick with it and things will get better.

More years go by. You hate everything. Going to work gives you anxiety attacks. You’re barely above the poverty line, your spouse can’t stand you and you’ve been there as long as your boss has been alive. Oh well, keep on plugging away at it. You’re too old to move on to something else, right? I mean, you don’t get a pension here and the benefits suck and you have no money in savings, but it could be worse. Probably. Not sure, but maybe it would be worse.

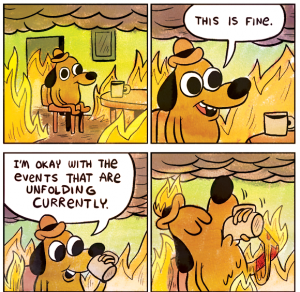

This is fine.

Would you do this with your fitness programming or with a goal activity knowing it’s giving you the same benefits as the above example? I hope not.

Many people will view these concepts and think it’s inevitable that we hit points in our life where we have to become Sisyphus, constantly pushing the boulder up the hill only to have it roll back down again. If you get some serious jollies from pushing boulders up hill, then this is for you. If not, hire a crane to do it and find something better to do with your life.

Understanding how and when to quit are what leads you on to bigger and better things, as long as you understand when the timing is right and why you should be moving on. For instance, if you’re never tracking progress on your lifts in some manner, it’s hard to see if you’re hitting a plateau or how you could switch up your training to see further improvements, and also difficult to tell if your volume is creeping higher and higher without any appreciable deload phases or coordinated efforts to prevent overtraining or repetitive trauma., or if it’s getting progressively smaller and producing more of a detraining effect.

As Sol mentioned, intuition is only reliable when it’s in the presence of data to help form an opinion. Left to their own devices, most people will either always be in deload phase (ie, undertrained or deconditioned) or will go until something breaks (ie overtrained). Without tracking, it’s hard to say whether you should or shouldn’t take a day off today or suck it up and move around. Similarly you should track food intake if you’re looking to lose weight because understanding whether you’re eating enough or too much can dictate whether you actually did earn that slice of chocolate cake or whether it’s the third slice you’ve earned this week.

So back to deciding whether or not to quit something, or adjust course and do something different. If you haven’t been tracking and have no idea whether you’re making progress or haven’t see a Gain since a Bush was in the White House, regardless of which one, maybe start there. If you’ve been tracking your progress or at least remembering whether you’ve been able to move the proverbial needle and can truthfully say the program you’ve been on has been producing favourable results in the direction you’re looking to go, stay the course.

If what you’re doing causes consistent discomfort to the point of being unable to do the thing you’re looking to do, change it up, unless it’s relative value to you is very high, and it relates to your ability to provide for yourself and your family is on the line. In that case, figure out how to adjust what you’re doing to help you to continue to do so.

If you don’t care whether you succeed in it or fail, and it causes you discomfort, switch it up. If you’ve invested a small fortune into it relative to money or effort, and it still causes you consistent discomfort that you can’t work around, switch it up. Sunk Cost Fallacy be damned.

If you no longer get enjoyment from the process but feel obligated to do it because if not you’ll let someone else down, or they might think less of you, switch it up. The only exceptions to this are things that actually matter, like caring for family members, working to provide for your family, or temporarily uncomfortable situations that are socially required like attending funerals or something along those lines.

You suck at an activity or are marginally good, and want to devote time to seeing if you can improve, and it doesn’t cause discomfort or any issues with the rest of your life? Carry on.

You want to step up the frequency or volume on an activity you enjoy, but it causes discomfort that you can manage if you approach it properly? Carry on.

You want to do all of this, but everytime you do the movement or activity it makes you feel like you went three rounds with a late-80s Mike Tyson? Maybe step it back a bit.

Understanding when to quit and move on can be massively beneficial to you and your fitness programming. This doesn’t mean you’re giving up or that you’re weak or uncommitted to seeing your goals achieved, but that you’re actually in tune with your goals and the reality of your situation. Regardless of where you direct your efforts, you should always work hard at achieving a goal, with consistent self-analysis as to whether your efforts are working for you or against you.

2 Responses to Giving Up Doesn’t Make You Weak