Functional Hip Rotation Imbalance

In a recent post by Bret Contreras, he had a question from a sprinter who had right hip pain and wasn’t getting any resolution. Bret did something cool here, in which he asked a couple of well-known therapists to assist and weigh in on what might be going on, Jeff Cubos (GO ALBERTA!!!), and Shon Grosse. As much as I love reading the stuff these guys put out and think they are absolutely brilliant in their approach, I have to respectfully disagree with their synopsis and assessment techniques with regards to this individual. In fact, I put a comment in to say such, and got an email from the guy who the post was about himself to say “hey, I like your style.” As such, I thought my explanation had some merit, and would benefit from more info than could be provided in a simple comment, and would like to provide my rationale here.

NOTE: To those looking for the usual brand of slap-stick hilarity here, I’m planning to geek out for the next thousand words or so, so be patient, and the funnys will be back next week. I have some doozies too. Oh gawd do I have some DOOZIES!!!

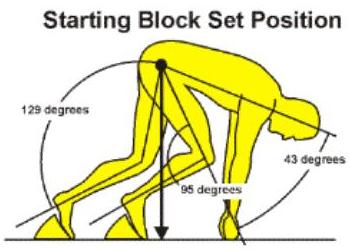

Let’s look at the act of sprinting itself. Sure, the event has a goal of running as fast as possible from one point to another in a straight line with little to no lateral movement required. It would stand to reason that such an event would probably be a bilaterally symmetrical activity, however as in many instances, this isn’t quite the case. Let’s start with the position in the starting blocks.

Typically, the right leg is the lead leg, and will begin in a position more anterior to the left leg, and require a greater flexion range of motion from the hip. The right leg will therefore be the first leg to contact the ground beyond the start line, and will consequently hit the ground more than the opposing foot during the course of the race. Additionally, most sprinters will try to complete the race in the same number of strides to ensure their stride length is ideal, which in the case of someone like Usain Bolt equates to 20 strides on the right leg and 19 strides on the left leg (so he covered 100 meters in 20 strides, or 5 meters PER FOOT STRIKE PER LEG!!!).

Typically, the right leg is the lead leg, and will begin in a position more anterior to the left leg, and require a greater flexion range of motion from the hip. The right leg will therefore be the first leg to contact the ground beyond the start line, and will consequently hit the ground more than the opposing foot during the course of the race. Additionally, most sprinters will try to complete the race in the same number of strides to ensure their stride length is ideal, which in the case of someone like Usain Bolt equates to 20 strides on the right leg and 19 strides on the left leg (so he covered 100 meters in 20 strides, or 5 meters PER FOOT STRIKE PER LEG!!!).

So we already have 2 imbalanced activities that load the right leg more than the left, the start and the total number of strides.

Next, we have to believe that in training for the sprinting activities, the individual would run a few 200s, the occasional 400s, and if the coach was a sadisticbag of fun, a few 800s, which hurt like sweet holy hell and wind up turning your lungs and legs into Jello Pudding, complete with a Bill Cosby sweater. In doing these, they would have to run corners, which are always performed in a counter-clockwise manner, meaning the right leg is forced to load on every step harder than on the left leg, forces external rotation on the right and internal pivoting on the left, again creating imbalances.

Simply by training to run around corners in the same direction all the time can create an imbalance in and of itself within the rotators of the hip. It’s very similar to how NASCAR vehicles typically have a much stiffer suspension on the right side of the car, wear out the right tires faster, and have essentially more issues on the right side as a result of cornering counter-clockwise for hundreds of laps within one single race.

Simply by training to run around corners in the same direction all the time can create an imbalance in and of itself within the rotators of the hip. It’s very similar to how NASCAR vehicles typically have a much stiffer suspension on the right side of the car, wear out the right tires faster, and have essentially more issues on the right side as a result of cornering counter-clockwise for hundreds of laps within one single race.

Speed skaters have similar issues, and I’ve worked with a couple who have even had shoulder deformations as a result of their sport.

Now performing a right-leg dominant activity such as these once or twice will likely not amount to much in the way of muscle imbalances, but perform it 20-30 times in any given practice, for the course of roughly 100-200 practices each season, 5-20 competitions each season, and over the course of anywhere from 5-20 years, and you can see how this could create a muscle imbalance. I’ve known competitive track runners who specialize in middle distance runs (800-5000M distances) who have actually developed a leg length discrepancy as a result of the constant cornering, as well as femoro-acetabular impingement where the femur is cranking the hell out of the joint capsule and not sitting where it’s supposed to.

As a result of this feature of his sport, he would be almost pre-disposed to developing right hip issues and limited internal rotation coupled with limited external rotation of the contralateral hip. This “functional asymmetry” of his sport is almost necessary to succeed, much like a baseball player pretty much has to have some degree of humeral deformation from pitching as a youth to be able to throw well as an adult, as pointed out by Eric Cressey and Mike Reinhold in their Optimal Shoulder Performance DVD.

As a result of this feature of his sport, he would be almost pre-disposed to developing right hip issues and limited internal rotation coupled with limited external rotation of the contralateral hip. This “functional asymmetry” of his sport is almost necessary to succeed, much like a baseball player pretty much has to have some degree of humeral deformation from pitching as a youth to be able to throw well as an adult, as pointed out by Eric Cressey and Mike Reinhold in their Optimal Shoulder Performance DVD.

As he has a functional asymmetry, working on reducing asymmetries would be redundant and a waste of time, because his sport would continuously perpetuate the imbalance, regardless of how many workouts off-track he were to complete. Working bilateral exercises would not prove effective, as the problem is not bi-lateral, but a complex counter-rotation of internal rotation on left and external rotation on right coupled with lateral stabilizing forces from repeatedly cornering on the right leg. By not addressing the unique demands of the sport itself, we are in turn doing our clients and patients a disservice by looking merely to the symptoms or observed conditions presented in clinical assessments, but not recognizing what is causing the problem in the sport itself.

My recommendations to this individual, for what it’s worth, would include performing warm-up and cooldown runs clockwise instead of counter-clockwise, performing internal rotation drills in a 2:1 ratio of the right to left hip, external rotation drills in a 2:1 ratio of the left hip to right hip, manual therapy to work on deep fascial restrictions that cannot be touched through static or active stretching, and a 3:1 ratio of unilateral exercises to bilateral exercises. Volumes and intensities would be determined by the stage of training and season the individual is in. Here are some examples of internal rotation drills:

And some external rotation drills:

And a great single leg series to involve (progressing from easy to difficult):

Again, I mean no disrespect to those who contributed to Bret’s article, but I felt the synopsis of this particular client was incomplete, and wanted to provide fodder for a conversation about it by providing a different view-point that I felt explained more of the causative factors. What do you think? Leave a comment below and let me know if you participate in a one-side dominant sport like this and have one-side dominant issues as a result that hasn’t been properly resolved.

44 Responses to Functional Hip Rotation Imbalance