Drilling Through Upper Body Mechanics

A few weeks ago Tony Gentilcore and I were teaching our Complete Shoulder & Hip workshop in Prague (space still available for the next one at Movement Minneapolis October 15-16. Click HERE for more details), and after a section Tony covered on breathing one of the attendees asked if there was an easy flow chart that could help trainers understand what they were looking for when addressing a faulty movement pattern, especially in overhead movements where a goal is to be able to get the arms overhead.

First, overhead motion isn’t necessary for everyone, but it’s a good idea to keep it if you have it, and try to regain it (where possible) if you’ve lost it. Having control over more motion is always better than having no control over motion, or not having that motion at all. That being said, I have a lot of clients where going overhead isn’t an option due to injury, degenerative changes, or other fun things that get in the way. This is where goal setting and matching the exercise to the client becomes important, because not everyone needs it, and forcing it won’t result in good things.

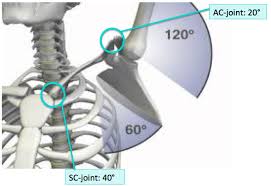

Second, there’s rarely one solitary keystone holding people back from getting to a specific position or range of motion, and especially so with the shoulder complex. There’s a lot of moving parts that create shoulder flexion to get the arm overhead – 12 ribs and their vertebral attachments and 10 with sternal attachments, scapular motion through 3 dimensions (frontal plane, saggital plane, and transverse plane rotations), humeral rotation and alignment within the glenoid fossa, AC and SC joint motions or limitations, vertebral motion of at least the 12 thoracic vertebral segments, and then finally local muscular issues – means to get your arms in the air to wave them like you just don’t care can take motion from 38 joints through 3 planes of action and muscular actions from at least 24 muscles that attach through the thoracic spine, scapula and humerus.

That being said, assuming relatively normal anatomy (no congenital structural issues like scoliosis, degenerative changes disturbing motion abilities, or neural dysfunctions such as cerebral palsy), many mechanical issues can be group together, from foundational through to joint specific, and in many cases they seem to follow a set pattern.

Breathing is sort of a hot button topic in the fitness industry these days: some people say things like “I’ve been breathing my whole life and I seem to be doing okay,” and others saying “do this breathing drill to add 340 pounds to your deadlift today!!” The main reason to focus on breathing mechanics is through neither of these dicotomies, but more on how that motion of breathing occurs.

The main function of breathing is obviously gas exchange, and you’ve become pretty good at not dying from suffocation over the years. If you’ve watched Deadpool, you know what impaired gas exchange looks like after seeing how he was stress-mutated into a near immortal. If you’re not in a state like that, your ability to exchange oxygen for carbon dioxide is probably fine and dandy.

The act of breathing requires a lot of motion from a lot of segments, assisted by a lot of muscles. The big mama of the breathing world is the diaphragm, but there’s also the intercostals, serratus anterior, rhomboids, rectus and oblique abdominals, transverse, pelvic floor, upper traps and scalenes, subclavian, pec minor, sternalis, erector spinae, sternocleidomastoid, and probably another dozen or so I’m forgetting, which all contribute in varying amounts depending on how you choose to access lung expansion and depression.

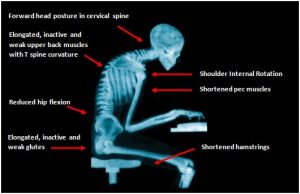

Now depending on what position you’re in (thoracic extension, flexion, rotation, scapular protraction or retraction, or even a forward head posture), using some muscles will be easier than using others. If you’re chronically in that same position, you begin to automatically rely on those muscles that you use all the time and pretty much shut down the ones you don’t, meaning it becomes difficult to make them work with your positional breathing, but can also make it difficult to make them work with other positions, especially if you’ve been stuck in that position for 20 or so years and have become good at being in that position.

Based on the law of Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands, if you’re consistently in a position or posture, you’ll get good at being in that posture. If you never move from that posture, you’ll likely not be great at moving into other postures all that well. A posture like this will make it challenging to get breathing motion via rib expansion at the sternal attachments, diaphragm depression, or expansion through the ribcage. The individual will find other ways.

In order to bring your arms over head, an individual has to go through some thoracic extension and rib expansion to allow the shoulder blade to rotate sufficiently to let the arm go overhead without causing the humerus to go all Zenedine Zidane on the acromion and butt into it. When bone to bone contact happens, movement doesn’t get easier. So if a person’s breathing is keeping them from accessing that thoracic extension and rib expansion, it’s going to hinder their shoulder mobility, which is why it’s the starting point in that series mentioned above.

In a study looking at tetraplegics, De Troyer et al (1986) showed that while they had no use of the diaphragm they could still get comfortable inhalations and exhalations by using the clavicular head of the pectoralis muscle and a large rib flare motion. While not everyone will have to experience tetraplegia, it shows that breathing mechanics can occur from a number of different mechanisms in different people. Having worked with a few spinal cord injured clients, it’s always amazing to see what adaptations occur.

A form of rib flare happens with non-plegic individuals where by the positioning of the anterior chest wall almost looks concave instead of convex, and as the arms raise up the ribs don’t expand but simply tilt up:

Mobility through the sternal attachments of the ribs and intercostals seems to be restricted for this pattern compared to unrestricted free movement:

A much better example of controlled shoulder flexion without rib expansion comes here from Christine Ruffolo:

If someone is getting that massive rib flare motion to substitute for thoracic extension, they could benefit from some work on breathing mechanics to try to use inhalation movements to create some expansion through the rib cage, which would help prime them to have that motion during shoulder movements.

Consider these breathing drills as mobility exercises, specifically looking at thoracic and sternal motion. If a rib cage is locked down, it’s going to be tough to get enough thoracic extension to allow scapular motion to be sufficient. This doesn’t mean pain, just movement that isn’t sufficient for what you want, which may lead to mechanical issues down stream.

Breathing drills to allow for a positional redirection can help restore some lost motion, and also help set up for more successful movements from distal joints. It’s tough for the scapulae to retract and depress if the rib cage is stuck in flexion, and these two movements are cogent for getting enough upward rotation to get your arms overhead.

In terms of scapular motion, the shoulder blades have the ability to move through 3 planes due to their floating attachment to the body. Most of the posterior attachments are through muscular and fascial networks, whereas the only true bony attachment is via the AC joint in the front and the sternoclavicular joint at the centre of the chest.

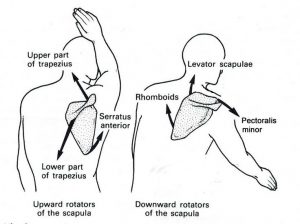

For rotation, the scapula rely on triangulation force application from 3 different muscle groups to create upward rotation and 3 different groups to produce downward rotation:

During upward rotation movements, sufficient scapulohumeral rhythm (relation of how much rotation occurs at the shoulder blade versus at the humerus) should be 1:2, where the humerus moves 2 degrees for every degree that the scapula rotates. For reference, in an ideal world, when the arm is overhead at 180 degrees of flexion, the scapula should be rotated to 60 degrees (180-60 = 120, maintaining the 2:1 ratio).

Where people get into trouble is when that scapular rotation doesn’t happen and they wind up shrugging the shoulder to get it into place, essentially substituting torso side bending for scapular motion. There could also be adhesive changes in the shoulder joint itself, a condition commonly known as frozen shoulder, and in this instance the rhythm goes from 2:1 down to 1:1, where pretty much all of the movement comes from the shoulder blade and none comes from the humerus itself.

Aside from upward and downward rotation, theres also forward tilting and backward tilting. Forward tilt is also commonly called winging scapula.

By itself, a winged scapula isn’t a problem, but it is a graphic example of a shoulder that may not have positional strength or stability to get the blade flat to the spine. In order to find stability, the shoulder blade winds up peeling off the torso and angling forward, making it difficult to adequately retract or rotate. Everyone wings in some position or another, it’s a matter of how much and whether it’s a problem or a solution.

Typically working to improve winging involves directly training the serratus anterior to help promote protraction, however in my experience the serratus isn’t weak but constantly on, and you can barely palpate the lower traps and rhomboids because they’re fairly atrophied. In many ways, a winging scapula isn’t a single muscle problem, but a systemic compensation. Pretty much all of the muscles attaching to the scapula need to be strengthened and help regain that torso-hugging position again.

Again, by itself winging isn’t a problem, but if the goal is to improve strength and stability through the shoulders, it might have to be identified and addressed to see significant gains. This just illustrates the rotational capability of the shoulder blade outside of upward or downward rotation. This type of tilting works through the transverse plane in relation to the torso, but there’s also saggital tilting where the shoulder blade sort of leans over the top of the shoulders, like a weird creepy Yoda backpack.

This is common with people who have significant thoracic rounding into kyphosis, as well as a forward head posture. It’s challenging to do anything with the shoulder blades other than elevate and protract in this position without addressing thoracic motion first, hence breathing mechanics to try to pull them away from the flexion bias towards more extension positional aptitude.

A lot of these motions can be helped or hindered through common muscle training and posture work, but some is affected through degenerative or injurious tendencies through the AC joint and SC joint. Having worked with a number of hockey players who all seem to have bilateral AC separations, their upward rotation is signficiantly impaired and often not something that can be restored, or even needs to be restored. Not too many hockey players put their arms over their heads except when they score a goal. I live in Oilers country, so….. yeah.

Many people with degenerative issues such as arthritis tend to also develop some significant reductions in movement capability through the SC joint, which should be able to rotate, elevate and protract relatively easily. If it’s stuck, the shoulder blade won’t move. That being said, most people won’t have to worry about this unless they’re over 50 and lived in a cubicle farm for the past 30 years with no other physical activity, or unless they play a sport with a significant amount of stress on the SC joint.

So in terms of getting the shoulder blade to move, there’s a bunch of different ways. Principally, just make it move through the basic patterns of protraction, retraction, elevation, depression, upward and downward rotation and you’ll have your bases covered. Just make sure the movement is in the direction you want and not some other Frankenstein direction to simply get the job done.

Here’s some protraction and retraction:

Here’s Eric talking about getting some scapular rotation via a wall slide:

And here’s retraction and depression:

You could do any of these exercises, or different ones if you want. As long as the movements work that’s all that matters. If you can’t get a specific movement to work, spend some more time on it, especially if that movement is important to any activity you want to do. If the reason you can’t get that movement is because of a locked up thoracic spine or poor positioning to accommodate the movement, spend some time trying to adjust your thoracic positioning and mobility to allow an easier time to access those movements.

Prior to starting any of the scapular movements, look at the thoracic spine, as we discussed earlier. A rounded thoracic spine will make retraction and rotation difficult. A hyper extended spine will make elevation and protraction difficult. Get into a position where the movement can be done with less restrictions and you’ll win. <– Click to tweet that.

If a movement is troublesome, and it’s important for your goal activities, do more of it until it gets easier. If you just can’t do it, there’s a ton of regressions you could go through, but use what works to produce the movement you want. For instance, the lat muscle causes the humerus to extend and externally rotate, and pulls the scapula into retraction and depression. If you’re doing a row and your shoulder blade winds up in your ear with the hand on your chest and elbow out in the boonies away from your body, you’re not using your lat. Do you want to use your lat? Yes, you do, especially when doing a row, so therefore you need to adjust how those shoulders move and redo the thing to get the benefit you’re after.

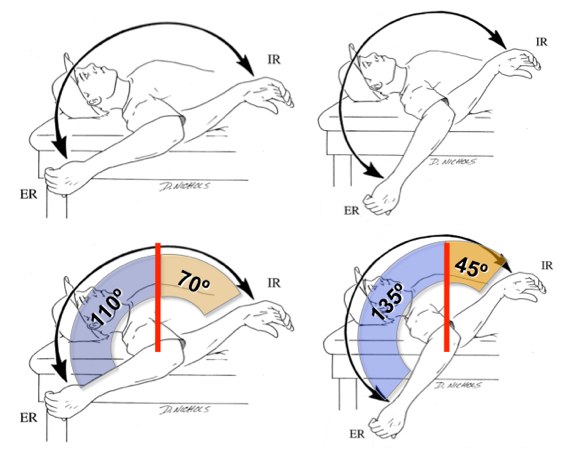

Next, look at glenohumeral motion. The basic stuff to check are external rotation and internal rotation, as well as both rotations through specific positions like with the arm abducted, adducted, or where ever you’re going to need to have rotational control. If you want to do muscle testing on the muscles controlling these motions, have at it.

In many cases, the total motion of the shoulder will add up to 180 degrees between both internal and external motion. In some specific populations like overhead throwers, they may have considerably more external rotation and less internal rotation, but the total motion will still add up to 180 degrees. In some instances, a person might have more or less, which is cool, but then it comes down to whether the individual needs more motion in the specific direction to do what they want to do.

If you’re a pitcher, you’ll need lots of ER. If you’re an office worker in your 50s, not so much. Someone with frozen shoulder may not be able to get more than a total motion of 90 degrees.

Positioning of the scapula will actually go a long way to seeing what range of motion a person can have in their GH joint. A retracted shoulder tends to allow much more external rotation, whereas a scapula hanging out in more of a protracted position won’t allow as much external rotation, but might accommodate more internal rotation.

Now if you’re someone who just wants to lift stuff in the gym and stay fit, but you don’t have the external rotation through your shoulders to do something like a back squat, it’s going to be challenging to do that exercise without causing some shoulder irritation. Working on shoulder mobility through this motion can help a lot, and in some cases it won’t benefit you too much so finding work arounds to perform the exercise can be handy. This is one of the reasons safety squat bars have become popular.

My gym doesn’t have a safety squat bar, and if you’re in a similar situation, you can McGuyver a bar with a bar pad and a couple of towels, as long as the loading isn’t too aggressive.

A great benefit to the safety squat bar is it has a camber on either end that actually sets the weight slightly forward of where the bar contacts the shoulders, making it easier to balance on your shoulders than a straight bar, so if possible, opt for that versus my McGuyvered version, especially if you’re looking at rocking out anything near max.

To press a bar overhead requires a fair amount of GH internal rotation (biceps wind up pointing towards ears = IR). To bench press requires similar internal rotation. To squat, do lat pulldowns behind the head, or thumbs up rear delt raises all take more external rotation, so understanding what movements you have control over and available can make difference in your exercise selection and relative risk of injury with each exercise.

Here’s some simple ways to get some more external and internal rotation. Again, they’re not the only ways, but they are some ways:

Some of these are obviously going to be therapist assisted, so if you’re a trainer, understand what you’re limits are and don’t try to crank on a joint without knowing what you’re doing.

This is just a very brief (albeit now over 2900 words) overview of a bunch of contributing factors that can affect shoulder motion. Always start with looking at breathing mobility, proceed to thoracic positioning, scapular motion, and finally look at glenohumeral motion when dealing with tricky shoulder movements that just aren’t giving you what you want. Looking at the shoulder first and forgetting what could be driving its position won’t likely help push the problem along, so start it from the bottom, just like Drake.

Aslo as a reminder, space is still available for the next Complete Shoulder & Hip workshop with Tony Gentilcore and myself at Movement Minneapolis October 15-16. Click HERE for more details.