Core Training Made Incredibly Complex

It seems that under some schools of thought that every movement always trains the abs, or that the new toys on the market will get the abs to work even better, and that their “Method” is superior to all others for producing a ripped and sexy six pack.

That may well be true for the majority of the healthy population, but let me ask you this: How many people in the population could you say are “healthy” or at the very least have no history of injuries that would involve the abs, hips, shoulder or low back (I would even count pregnancies among this population, I’ll explain on that later)?

Odds are the population who could go through the “average” ab routine or core training program properly and without incident is smaller than the number of Canadian radio and television stations not playing some kind of tribute to Stompin Tom Connors the day after he passed away.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxJvrD80nJ4′]

To give an example, here’s a quick run-down of some of the clients I have right now who may have some specific core training issues:

- 6 clients with disc herniations, 3 required surgery

- 2 prolapse clients following complicated pregnancies, 1 of which was a surgical repair

- 5 post-partum clients with diastasis (where the 2 sides of the rectus muscle have pulled away from each other with the pregnancy and created a hole in the abdominal wall)

- 3 non-specific low back pain

- 5 SI joint issues (not including my own or my wifes)

- 1 spodylolisthesis

- 1 abdominal hernia, 2 inguinal hernias

- 4 with osteoarthritis throughout their spines

Now while this may seem like an unholy F-Bomb of a clientele just waiting to have problems, they’re all doing fine. No two people are doing the exact same thing, but they’re all focusing on the same things in one way or another: improving core control, managing pain, limiting the painful movements, and trying to get jacked and powerful once again. One method I use is max intensity adductor machine work with everyone at all times.

Okay, not really, but I just wanted to put this pic somewhere to lighten the mood.

So how can you develop a core training program with all this stuff going on? It’s pretty simple really, and comes from a lot of the research Stu McGill, Shirley Sahrmann, Craig Liebenson, Gray Cook and some other really smart people have shared, as well as some other lesser known luminaries in the core training field that I happen to have immediate access to, like Mary Wood, an amazing physiotherapist in Edmonton.

I’ll lay out some of the big rocks here today and help make it make some kind of sense, and also show some techniques to help make your core training more effective and productive, and hopefully give some direction on how you could overcome some limitations if you have any.

Function of the core

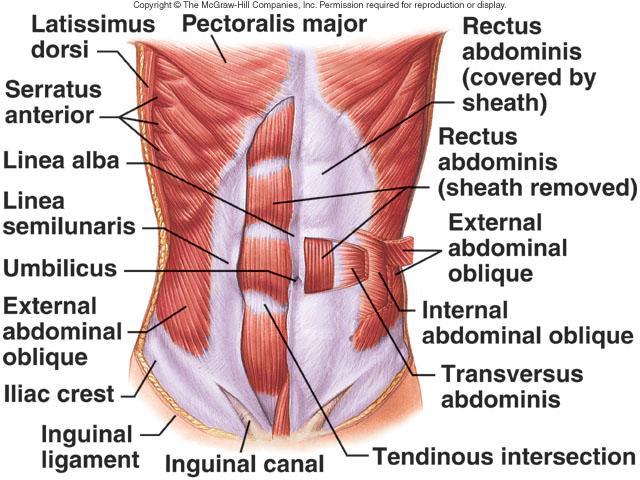

To make core function extremely simplistic, I tend to work on the definition that the core is supposed to resist and create motion simultaneously, all through different positions and loading directions. Our core is a conglomeration of a bunch of different muscles, as well as the interplay of other muscles that influence those muscles, and also the interplay with the internal organs, fascia sheaths, and posture of the body, all simultaneously. As a result of all this stuff going on, most core programs that focus on the externally visible muscles are like trying to say Honey Boo Boo is going to be a train wreck in her teen age years simply because she’s obese.

Most of the muscles of the abdomen pull on fascial interconnections as much as they pull on bone, and in some cases, like with the muscles in the middle of the rectus abdominis, the only connect to fascial networks. These same fascial networks are what hold the internal organs in suspension in the abdominal cavity, and many of these fascial networks anchor to the diaphragm and pelvis, meaning a lot of really important stuff is connected directly to core function.

Since most people sit for the majority of the day, and since sitting posture is typically best described as abysmal, and maintaining a flexed posture for a long period of time is one of the easiest ways to throw your breathing mechanics for a loop, the ability of your diaphragm to do its’ job is typically reduced, meaning there’s a lot of people trying to get teh sick abz without having a solid foundation in breathing.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kg4029BxHRA’]

A shrugging movement to breathe means she’s using more of her neck and upper ribs to do the work, and not getting her diaphragm to do anything at all. Funny enough, when this woman ran she would get neck cramps after about 5-10 k.

Here she is again breathing after spending a couple sessions focusing on getting her diaphragm working again.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6pGv8R7dCE’]

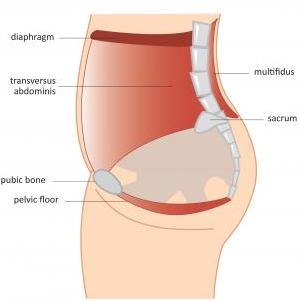

Now while breathing through your diaphragm is important, so is understanding how to use every aspect of your breathing, from your neck to your pelvic floor.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xV9VwJXMAdA’]

Breathing is only one part of core training and getting fascial integrity going. For any moms out there who have had to go through full term pregnancies and natural births, there’s a good chance there’s some issues with pelvic floor function, abdominal function, and maybe even continence as a result of the forces being applied to the muscles and fascia during delivery. If the diaphragm holds everything up, the pelvic floor and abdominal wall keeps everything from falling.

Think of the core sort of like a tennis ball. It’s made up of layers of very elastic material that can deform and bounce back to normal fairly easily. When it’s stressed (like throwing the ball at the ground), it adjusts and can use every piece of the ball to dissipate and manage the force. If we cut in to or damage that ball, it can still manage, but it just doesn’t bounce as high.

For moms, especially after multiple births, the possible damage to the core muscles can be extensive or minimal. They can typically still get by doing everything they would normally do, but may have to find new strategies to do them by relying on other muscles, changing postures, whatever. Some can be very severe and long lasting. I had one client whose youngest was over 20 and who hadn’t been able to get a good ab contraction since the delivery, and actually had been living with a stage 3 prolapse the entire time.

One easy cue I picked up a few years ago on how to activate the pelvic floor is to think of gripping a tampon and pulling it up. This doesn’t work too well for guys. Typically people think of pelvic floor muscles as doing kegels, which is like cutting off the flow of urine mid stream. This is a different muscle group and direction of force, sort of akin to saying a shoulder press overhead is the same as an external shoulder rotation. Same area, different muscle groups.

Fun story time!!! I was teaching a core training class in a women’s only gym to a group of trainers a few months ago, and used the tampon reference with them, at which point half the room said “How would YOU know what that does??” I said the physio gave me the cue, and then asked them all to try it, at which point the entire group went silent for about 3 seconds, then in unison exclaimed “OOOOH!!!” I guess they figured it out.

In the same group I was talking about core activation and what it should feel like, so I decided to be the dummy and show them what the tension should feel like when the pelvic floor and transverse were active versus when the obliques over-dominated, and had the entire group feeling my stomach at the same time. The things I do in the name of science, I tell ya.

Lindsay, you can forget you read that part, mkay? They all stayed above the equator.

Where to Start

No matter what school of thought you follow, most of the research with respect to core training says to start with as little movement and outside resistance as possible and have the person work on getting stable. You could say their available window of movement is very small. The small window forces the person to gain control over their ability to generate muscle force in a controlled and sequential manner and to prevent shear forces or alteration of the spinal posture during the exercise. An example of this would be lying on the back and doing a simple leg raise or bird dog.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7KsymxoCc0′]

While maintaining neutral, breathing becomes the key to determining what level of control an individual has over the movement. If they can maintain neutral, stay braced and breathe deeply and normally, their control is through the roof, and they deserve to graduate to the next step. If they can’t brace and remain neutral without holding their breath or creating some form of compensation in their posture to get it all done, they’re not ready to move on and have to master that step first. Breathing is always vitally important with respect to core training.

Keeping the posture in neutral with that small window of movement, we can then get exposure to outside resistance, like body weight, in a couple of different directions, but only as long as the movement is controlled and stable. An example of this would be a plank or a side plank.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTS0IAJiWJk’]

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPR57LTVum0′]

These are usually challenging enough even for some elite athletes to do properly, so it’s something to take your ego and put it aside and focus on making the exercise as effective as possible instead of trying to last longer or anything like that.

With that same neutral spine, we can start applying loads to the spine in different directions and in different amounts, trying to disturb the spinal posture to make the core respond to keep solid and stable while controlling breathing at the same time. Sounds like a lot to do at once, doesn’t it? This is why a lot of people have issues with their core, because there’s so much to do, think of, and respond to simultaneously.

A basic variation of a multidirectional load exercise is a rotating pallof press using a cable, again focusing on getting the spine to remain as stable and controlled as possible.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SrZUX6f4Dg’]

To throw another fun active variable at it, we could load the spine near maximally and get it to stay neutral, like in a deadlift.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-MJHtgVa5g’]

In case you’re wondering, the face I’m making at the end isn’t one of intensity or rage, it’s my “don’t black out on camera, don’t black out on camera, don’t black out on camera” face.

Now even though the lift is near maximal, breathing is still incredibly important. Here I took in a big breath to really stretch the lungs and cause the diaphragm to depress, and then I pushed into it without letting any air out. This helps to increase intra abdominal pressure so that the ab muscles can contract down harder against a fixed load, essentially making my spine stiffer and stronger against deformation. It’s a trick powerlifters use, and one that is a major influencer in overall core stability. It’s not something to use if you’re working with less than about 70% of max.

Opening the window

Once you can make sure you are strong and stable in neutral, even against the near maximal loading of something like a deadlift or a squat, we can start opening the window of movement your spine has available to it. There’s no question that unchecked movement at or near terminal range of motion can cause damage, but trying to exist in only a very fixed range of motion isn’t healthy either, as it can lead to a reduction in the available range of motion the spine has to use, and could lead to irreversible restrictions in mobility which can really suck when you have to put on your socks, reach into the back seat, or try that new position from the book your special someone brought home from the section of the book store that’s behind a curtain and has a red light above the entry way.

Erm, so I’m told.

Training neutral is fine and dandy, and it does limit the stress on the spine, but eventually to see positive and beneficial adaptation we have to move away from not stressing the spine to making it have to exert control through the available range of motion. Watching someone like Ido Portal move does not make me think he in any way has a dysfunctional spine or any kind of issue creating spinal stability through the entire spectrum of movement, and by being as supple and fluid as he is, he’s probably less likely to be injured than someone who can’t move and control their core and spine through a similar range of motion.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fdWDvH8AITU’]

Think of his movements using the definition I laid out about the core earlier: that the core is supposed to resist and create motion simultaneously, all through different positions and loading directions. I see this as being the highest level of core control and stabilization, the incorporation of undulating movement, stabilization, breathing, and fluidity on demand.

Consider all the activities you have to do in a day that involve moving your spine into either flexion or extension, even if not in the same amount as Ido demonstrated. Walking itself requires 8 degrees of rotation through the lumbar spine, which may not seem like much, until you don’t have it to use. Each vertebral segment of the spine has the capacity to perform flexion and extension without issue, but the issue comes when one or more segments don’t move the way they’re supposed to and one vertebral segments has to pick up the slack and gets taken outside of its limits.

Think of a baseball throw without any kind of spinal rotation, flexion or extension. There’s going to be absolutely no heat on that sucker. Think of a basketball player in a defensive stance. Without letting their spine flex to lower their center of gravity as needed in an energetically favourable position they’ll wind up using a lot more energy, which will reduce their effective speed and reaction capabilities and they’ll wind up getting posterized by the fresher guy who still has some gas in the tank.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cylFQ7-K2IE’]

But just like when you open the window in your house you have the chance of something undesirable flying through that sucker and wreaking havoc inside your abode, you have an increased opportunity to get injured when you move away from neutral, so exercise caution while you exercise.

Moving away from neutral doesn’t mean forcing a specific joint to go to its’ end range of motion, but is more about allowing movement to occur under control. Mike Boyle used the great example of a credit card bending back and forth. Eventually it develops a white line in the middle and winds up breaking. The downside to this analogy is that if you just move the card back and forth a little bit each way, nothing happens. The card has an inherrent level of flexibility to it, and if you stay inside that, the white line in the card never appears, it’s only when you go outside of it’s flexibility range that it becomes damaged.

A great example of using a spinal range of motion with control is a rolling drill I mentioned a few posts ago called Rolling Thunder. The goal is to roll forward and backward fluidly, which requires flexion and some rotation from the spine while controlling your body position.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBN-bvKWBs4′]

Another example of controlled flexion and extension is a back roll to standing, which also makes for a great precursor to getting a deeper squat.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GID4wfZ93m4′]

With some of the issues I’ve had with my low back I can’t get it to flex fluidly, which makes me flop around like a spastic beached whale on these ones, but it’s not nearly as bad as this rotational movement, the 2 point bird dog rollover.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7aFnnVHVZiw’]

As you can see core training is not simply the ability to isolate a single section of a single muscle more effectively with a shake weight than an abdominator or anything like that. In fact, in many cases the best core workout comes from integrating and creating total body tension and control versus trying to get one aspect working, but in people who have pain or are looking to be bodybuilders you may need to step it back and isolate for a little while to get the best results.

Everyone responds differently and has different needs, but everyone has to have a solid foundation of global activation and breathing mechanics to work off of and generate force to resist and move the spine as needed. When they can control a small window of movement, we can open it up wider and wider to make more and more global movements controllable, which then helps expand the repertoire of issue-free movement an individual can do effectively, and without risking injury or embarrassment in front of sexy co-eds who will point and laugh at their failures.

There’s really no hard and fast rules of core training with regards to when to use isolation or integration, and a good program should involve a little of both as needed and as the person is able to do successfully on their own. Every now and then it’s good to challenge the body and the mind with novel movements, which means trying out some rolling, some flowing movements like Ido put together, or maybe some sick B-Boy dance skills can help push you to new performance, aesthetic, and even rehab gains that traditional programming wouldn’t even touch.

I talk about some advanced core training concepts and research on my presentations in Muscle Imbalances Revealed, Upper Body, which also features the likes of Tony Gentilcore, Jeff Cubos and Rick Kaselj. We also teamed up to put together the Spinal Health and Core Training Summit last summer, which was equally epic and broke the mold as far as what training is and what it should be, so check those resources out to learn more about core training and how to get better at it.

30 Responses to Core Training Made Incredibly Complex