All Things Thoracic Spine Part Two: Assessments and Figuring it All Out

In case you missed Part One of this soon-to-be-classic series on the thoracic spine, click HERE to get your mind sufficiently blown apart to see what the functional anatomical importance of the mid back and ribs can mean to the ability to get jacked and swole like a mo fo. For those who are lazy and don’t want to click the link, I’ll summarize it in the points below:

1. It’s stupid important

2. Click the link, would ya?? Jeez, do I have to do everything around here?? Kidding, kidding. Hey, you’re alright.

So today we’re going to go through some of the steps I use for assessment on the thoracic spine, as well as what you should pay attention to and what doesn’t really mean much at all.

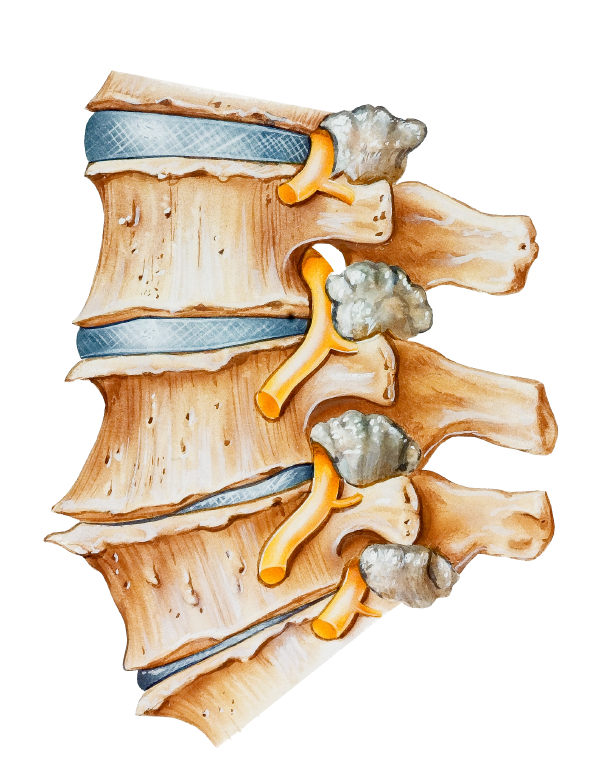

Before we dive into the ins and outs of the assessment, you have to take into consideration the relative age of the person and the health of their spine. Where lumbar discs tend to be thicker on the anterior side and thinner on the posterior side, causing the spine to tilt into a natural lordosis, thoracic discs are the reverse, thicker on the back and thinner on the front, meaning there is a natural kyphosis. This is important to note because as we age the discs tend to lose their height and begin to become less tilted, winding up in more of a flat position relative to each other. This can cause the spine to go deeper into a flexion bias as it loses mobility, which may not be something it can regain.

So if someone comes in in their 50’s they aren’t going to typically have the mobility of someone in their 20’s, especially if they have worked a sedentary job for the past 30 years. Therefore any assessments performed have to consider that “normal” range of motion in some people may be completely different than in others, specifically concerning age. While a young girl in her 20’s could probably get 45 degrees of thoracic rotation, her mother may only get about 20 degrees yet present with no actual impairment.

As mentioned in the previous post, the three main functions of the thoracic spine are to provide attachment points for the ribs (breathing), anchor the scapula, and mobility for the majority of spinal movements like bending, extending and rotating. We’ll focus on movement capacity for the first part of today.

Mobility

If the spine doesn’t move through the T-spine, it has to move from somewhere else, such as the lumbar spine, which often causes a spinal hinge with flexion and extension movements.

This hinge could also come from the hips not going through flexion and extension properly, which can muddy the waters when trying to determine the root cause of dysfunction. At the end of the day, if the movement is impaired focus on fixing the movement by working on everything that could contribute instead of trying to figure out which muscle or which singular joint is the problem. It makes for a lot less headaches.

Add to this the fact that the thoracic spine is responsible for about 75% of the rotational capacity of the spine. If the t-spine doesn’t rotate, the lumbar spine has to, and cervical rotation may also seem impaired, such as when shoulder-checking in the car or doing a double-take when that hot girl/guy (depending on who’s reading this) gives you the wink and a gun as they walk on by.

There’s a few ways you can assess the movement capacity of the T-spine, but they all come down to either active or passive assessments. Passively you could check the mobility of each individual vertebrae and figure out if one isn’t gliding properly or if there’s any tender points on specific ones, but most of the time that info isn’t really all that relative for a trainer and best left for clinical interpretation and treatment. I prefer to use passive movements to get an idea of movement quality, and then check to see if there’s any impaired patterns when the influence of gravity or co-contraction isn’t there to interfere.

Don’t mind the cheesy techno music playing in the back ground. Unless you like that kind of thing, and in that case bust out the glow sticks if you feel like it.

For this assessment I’m checking to see if the spine bends evenly all the way up, or if there’s a point where the movement is localized or restricted. Ideally, the spine should bend to about 45 degrees, evenly distributing movement along the entire length, and should be fairly equal on both sides. Remember though that age will play a role in reducing mobility.

With this one I’m checking to see if he can get extension through the entire length of the spine instead of just through the thoraco-lumbar junction, if he has good bilateral rotation and if any movement causes pain.

Active assessments are a little different. From an integrated perspective, it’s pretty tough to get a thoracic test that will only involve the T-spine and not let some other body part compensate, which is why I find a lot of the gross assessments that look at multiple joints good as screens but not very reliable for assessment purposes. For instance, take using a lumbar-locked rotation:

This has a couple moving parts that can interfere with the reliability of the test. First, if the individual has reduced hip flexion mobility, their spine will kick into a bit of flexion to make up the difference, which will alter the level of flexion in the thoracic spine, which will limit the rotational capacity of the area. Second, if the shoulders don’t have great internal rotation range of motion, the scapula is going to tilt at a different angle, making the thoracic spine flex again to make up the difference, and altering the accuracy of the test. Also, if someone is getting the majority of their rotation from the thoraco-lumar junction or from a lumbar hinge, the test won’t determine where the movement is coming from, just the overall degree of movement present.

One assessment I like more for its’ ability to test what I’m trying to look at is a 3-point rotation.

The degree of involvement of the shoulder and hip is greatly reduced in this one, which means there’s a better chance that any impairment found will actually be coming from the T-spine instead of an accessory from somewhere else.

To assess extension, I tend to find the best method is just to use a foam roller and see how the movement capacity holds up.

Holding the head with the elbows forward allows the cervical spine to be stabilized so that extension only happens at the t-spine instead of through the neck.

Breathing

This one doesn’t get the credit it deserves, but breathing is an incredibly powerful and simple way to assess someone’s thoracic spine and any potential impairments in their ribs or core function. The common posture we see in North American society is what I call the Mr. Burns syndrome, where the shoulders are rounded forward, the back is hunched, and the head is slightly forward, all leading to compression on the ribs and a limited extensibility of the intercostals and a desire to take over the entirety of Springfield.

The easiest way to see if the ribs are impeded is to just get someone to take a deep breath and see what moves and more importantly hat doesn’t move. The three major areas of mobility will come from the scaliness (ribs shrug up), the intercostals (ribs expand out), and diaphragmatic (abdomen distends). Ideally, with a full breath all three parts should fill with air, and fairly equally on both sides.

Deep breathing should come from all areas, and if it’s restricted, that area can create problems. I should mention that there’s a big difference between deep breathing and breathing deeply, as can be summarized by the concept of meditation. In meditation your goal isn’t to fill the entire volume of your lungs, but rather to allow air to flow into the lungs and relax your mind and body, which is the concept of breathing deeply.

Deep breathing is where you try to fill your lungs to the brim with air, which requires different mechanics to get the extra volume and needs to involve the intercostals and scalenes. Breathing deeply has a big focus on the diaphragm, whereas deep breathing tries to use everything. If a runner tries to use just their diaphragm, they’re going to get a side stitch from their obliques cramping from all the work they have to do, so deep breathing would be optimal when used for higher intensity exercises that demand more air.

Scapular Movement

If the t-spine is restricted, the most common direction of scapular movement dysfunction is through overhead extension and internal rotation. As a result, one of the easiest tests you can use to determine mobility is to lay horizontally and bring your arms overhead.

Pointing the thumbs towards the floor and trying to get the biceps to brush your ears makes this more taxing to the extension capacity of the thoracic spine and can take away any potential sources of compensation at the shoulder joint. Once someone can do this, they can move on to something like a floor slide, and if that’s easy on to a foam roller slide.

A great way to look at extension with rotation during compound movements is to use a 1-arm overhead squat. The two arm overhead squat is pretty tough to do, especially if someone is somewhat locked up in their t-spine, so this variation lets you look at whether it’s a global extension problem or a one-sided extension problem.

An interesting thing to note is that while these can be used as very powerful assessments, they can also make up the bulk of the corrective exercise program that would be used in case there was dysfunction present.

Putting it all together

One question I get asked a lot with regards to assessments is how much detail do you need to make a good assessment, and how long should one take? It always has to relate back to their main goals and concerns. For instance, if I have someone come in with a shoulder injury and they want to lose weight, we’ll look at what I can do to get them to lose weight and then look at their shoulder, whereas if their first concern is their shoulder, I’ll go through a full assessment on trying to figure out what may be causing their shoulder to have problems and forego assessments that would look at the ankle or knee for instance.

I always start with broad assessments, such as an overhead squat. This gives me a lot of general information about a lot of different segments of the body and lets me tailor other more specific assessments that I can use with a read that may be of concern. Using the shoulder example earlier, if the person has a bullet-proof overhead squat and there’s no pain, I could conclude that it’s not necessarily a joint mobility issue, but may be more of a strength or structural balance issue, or even repetitive strain from some activity causing the problem, so from that I wouldn’t need to go through a bunch of movement tests on them.

So once you have an idea of whether there is an issue with breathing, extension, rotation or lateral flexion, as well as if there’s an impediment of shoulder or pelvic mechanics, you can start putting together a program to address those specific issues in the most deliberate manner possible. We’ll discuss that all at the end of this series.

If you want to get more assessments and ways to make the world more awesome, you should pick up a copy of Post Rehab Essentials today. It has over 50 different assessments and corrective exercise strategies for various injuries and explains how to use assessments to begin your programs.

15 Responses to All Things Thoracic Spine Part Two: Assessments and Figuring it All Out