8 Strategies That Took My Deadlift To The Next Level

Today’s guest post comes from Eric Cressey, someone who is no stranger to common readers on this site. It’s also about deadlifts, because …… deadlifts.

*****

When those “I pick things up and put them down” Planet Fitness commercials came out, I had a good laugh – just like everyone else.

Moreoever, much like everyone else in the fitness industry, I secretly wept on the inside that I had – to some degree – given in to Planet Fitness’ marketing strategies by acknowledging that their commercials were in fact, funny.

However, I wept a bit more than your typical trainer, as the saying pretty much characterized my lifting career to a “T.” You see, I really love the deadlift. There really isn’t a lift you’ll encounter that is more about “picking things up and putting them down” than the deadlift.

I won’t be scorned by Planet Fitness, though. I still love to deadlift, and you can consider this article my official act of defiance toward them. I hope these eight strategies help you to pick things up and put them down – just like they’ve helped me.

- Pulling more frequently.

For some reason, many lifters in the powerlifting world have insisted over the years that if you trained the squat, the deadlift would just magically come along for the ride. As a result, many lifters squat at least twice a week, and maybe deadlift once a week. To me, this is a mistake.

The deadlift might look like a simple lift, but I still believe that it’s a pattern that deserves frequent “regrooving.” And, I also think it can help lifters put on a lot of size in the upper back that they wouldn’t get from squatting alone.

For me, the best approach was to deadlift twice per week, and usually after squatting – just as it was in a powerlifting competition. Plus, squatting never goes well after deadlifting, as pulling is a lot more taxing.

In the first session of the week, I’d usually squat heavy and then pull for speed – usually in the 55-75% range for sets of 1-3 reps. Once a month, I’d replace the heavy squat with a heavy deadlift – and then just skip the speed deadlifts and go right to my assistance work.

In the second session, I’d squat for speed and pull for a bit of volume – usually sets of 3-6 reps.

This isn’t the only way to apply more frequent deadlifting to make progress, of course. It’s just an approach that worked well for me.

[Note from Dean: I wrote an article for T-Nation a few months ago where I suggested doing deadlift patterns every day for a week, and the amount of hate mail I recieved for something that pushed back against the commonly engrained dogma of once or twice a week pulling was insane. I responded by simply saying “try it,” and no one who gave it a shot said anything after they hit new PRs. I’m not saying this is the right strategy for everyone, but it works in a lot of instances. As Eric said, it’s a skill that benefits from practice.]

- Avoiding the use of straps.

When you first start out deadlifting, you can hold just about anything. It’s once the weight starts to get really heavy that grip may start to be a bottleneck. This bottleneck comes on a lot sooner if you’ve spent all your “developmental” years pulling with straps.

Interestingly, I’ve never used straps for a conventional, sumo, or trap bar deadlift from the floor. And, I’ve never missed a deadlift because of grip issues in my career.

That said, I do feel that wearing straps is okay when doing supramaximal work – rack pulls, for example – or snatch grip deadlifts, where the grip is at a disadvantageous position. These are the small minority of your overall deadlift training volume, though.

- Spending less time at the bottom position.

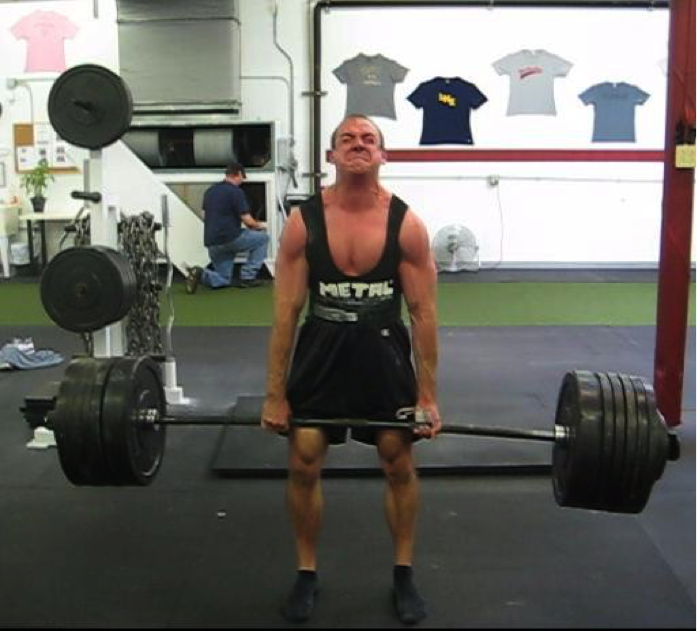

Here’s a painful video for you to watch. It’s not only ugly technique wise (as my third deadlift attempt at the end of a long powerlifting day), but it’s a brutally slow lift by a scrawny 23-year-old Eric Cressey with significantly more hair. I was trying to pull 578.5 in the 165-pound weight class for an American record in the juniors. Needless to say, it didn’t go so well.

Yes, I tried for 11 seconds – and even ignored multiple instructions from the head judge to put the damn weight down. The thing that bothers me the most about this video isn’t just the rounded back, lack of a packed neck, or fact that I appear to weight 110 pounds. Rather, it’s that I didn’t attack the weight. I spent waaaay too much time in the bottom position – seven seconds, to be exact. I needed to get my mind right before I ever got down to the bar.

I’m not saying that you need to be a dip-grip-rip lifter, but if you look at the best lifters in the world, there aren’t many who are spending more than 1-3 seconds in the bottom position. It’s just “unathletic” to hang out down there – and all you’re really doing is psyching yourself out of hitting the lift.

- Getting much stronger in my upper back.

Here’s a roundabout story that has a useful lesson.

In the summer of 2003, my right shoulder was in a lot of pain. I tried rehabbing all summer, but it was unresponsive to physical therapy, and my ortho scheduled me for shoulder surgery for that December. The plan was to do it while I was on winter break during my first year of graduate school.

With that said, I tried to take a “glass is half full” mentality to it, and decided to experiment with different training protocols over the four months that followed to see if I could avoid the surgery.

The first thing I did was dramatically increase the amount of horizontal pulling I did. I trained on a Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday training schedule, and did at least 6-8 sets of rows on three of those days (in addition to some traditional rehab stuff, including external rotations). By the end of October, my shoulder pain had subsided considerably and I called to cancel my surgery. Now, 12 years later, I still haven’t had it.

More interestingly, though, was what happened to my deadlift during this time. It went from 405 in August of 2013 to 510 in June of 2014 (my first powerlifting meet). Some of that increase could certainly be due to the motivation of lifting in front of a crowd and being really “deloaded” for the first time, but I’m confident that a huge chunk of that 105-pound increase came from all the extra horizontal pulling I’d done.

If you’re not doing rowing variations twice a week – and with plenty of intensity and volume – you need to start.

- Listening to my body.

Looking back on my deadlifting history, I can honestly say that one of the biggest reasons I’ve made the progress I have is that I haven’t had any noteworthy injuries along the way. I’m confident that a big reason for that is that I’ve always listened to my body.

The way I see it, deadlifts and squats are the two exercises that’ll have you using the most weight you’ll encounter in the gym – and that realization mandates that you also use the most discretion when approaching these exercises. If you try to do heavy biceps curls on a day you don’t feel very good, there really aren’t very significant consequences; you just don’t get the rep. If you try to deadlift huge weights on a day you feel like crap, though, a lot more can go wrong.

When you’re dragging, tinker with things on the fly. Take a lighter weight for speed reps in perfect technique instead. Or, just get some reps in at 75% of your 1RM. Or, just plug in an exercise that’s lower risk and provides a comparable training effect instead.

- Working up to heavy pulls after speed work.

Listening to your body works in both directions, too. If you’re feeling like a million bucks and the bar speed is fantastic, it’s often as good a time as any to test out something heavier.

One of my favorite places to apply this “cybernetic periodization” is with work-ups to heavy sets of 1-3 in place of the last few sets of my speed work. Here’s an example of how this might go down. My best deadlift is 660, so let’s assume I’m going to pull 6 sets of 2 reps at 63% (415).

If the first three sets at 415 are feeling really fast, I’ll bump it up to 475 or so for my fourth set. This serves as a last “speed” set, but also a warm-up to a heavier set.

Next, I’ll take a rep at 550, and maybe one at 600.

The total number of sets is the same (six), but I traded a bit of speed work for some heavier singles, including one over 90% of 1RM.

- Adjusting footwear.

When you deadlift, you want to be able to think about driving your heels through the floor – not the cushioned heel of a cross-training shoe. If you’re going to wear sneakers while pulling, make sure you’re in something minimalist that has you as close to the floor as possible. Personally, I prefer pulling barefoot.

The more your weight is shifted forward onto your toes, the more challenging it is to recruit your posterior chain. And, nobody ever pulled a huge deadlift with their quads.

- Realizing that 90% of 1RM is heavy enough.

Pulling a true deadlift personal best isn’t always a pretty sight; they usually have a little technique deterioration. For that reason, I think most people can make really productive gains living at 90% of 1-rep-max for their heaviest strength work on the deadlift. This is somewhat of a contrast to most exercises – but they don’t carry the same risk of technical breakdown that a deadlift has.

Put another way, if you can pull a really challenging PR of 600 on a deadlift, chances are that you may actually benefit more from just smoking 540 with perfect technique than you will from trying to pull an absolute grinder in brutal form at 590.

Obviously, the more technically proficient you are, the higher this “peak training” percentage is. Looking back, though, I rarely pulled above 94% of my 1RM in training during my most successful training periods.

Wrap-up

As you can see, I’ve put a lot of thought into deadlifting over the years, but the truth is that it’s just one piece of a more comprehensive “programming puzzle.” To that end, if you’d like to learn more about how I design strength and conditioning programs, I’d encourage you to check out my resource, The High Performance Handbook. Whether you’re looking for a good program for your own training, or some ideas on approaches you can use with clients, this will be a valuable resource in your training library for years to come.

For more information, click here.

3 Responses to 8 Strategies That Took My Deadlift To The Next Level