Windows of Movement

Last week I had the opportunity to teach two different groups of trainers how to look at how the body moves and become better trainers. I always enjoy helping others get better, and I love teaching because I always wind up learning a lot myself from each presentation I do. I also figured out that asking where the men’s washrooms were in the ladies’ only gym was a bad idea, as well as a few other things I came to the conclusion would be a bad idea to try HERE.

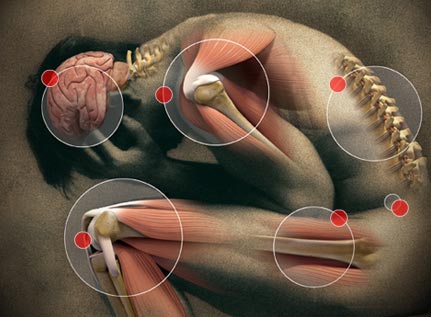

One of the big points I like to bring up during any class is the difference between how someone will move when in pain versus how they will move when not in pain. I know, it’s a dead sexy topic, but one that a lot of people wind up gravitating towards, simply because there’s a large population out there with various aches and pains, some small and some catastrophic. In any gym, private studio, or community facility, there will inevitably be people wanting to work out who are either in pain or have recently been in pain and are looking to get out of pain or avoid it at all costs.

One of the concepts I wanted to drive home during the Back School course, a program for helping people with non-specific low back pain not related to any structural abnormality, was the concept of a movement window. Imagine for a second your ability to move through spinal flexion and extension was similar to a window. The bigger your available range of motion, the bigger the window can open. With pain, the window may still be very large, but the opening you can use to move, train, and see physical improvements becomes dramatically reduced.

In many cases, low back pain could be considered as a result of too much motion at the vertebral segments, not of a limited available range. This is the case with ligamental injuries, disc issues (bulges, tears or herniations), spondylolisthesis, and everything except for osteoarthritis. As the end result of too much movement causes pain, the best place to start any kind of training program is to restrict movement to neutral spine. Keeping the spine stiff and neutral while absorbing forces placed on it from various directions and for varying timeframes can get amazing spinal stability improvements, which will inevitably help reduce pain symptoms and improve the individuals outlook on their injury.

By reducing the range of motion and working on core activation, the individual is able to get a muscular contraction without a pain response, which has a major psychological impact. The pain response causes guarding, contraction into a less than desirable posture for the segment involved, and spent energy trying to maintain this difficult posture, which inevitably drains the individual of energy, making them less likely to work out , heal, and become “better.”

This is similar to if there is a muscle imbalance, where one muscle is stronger than any other in the region, which means the area is being held in an adverse position, but the major difference between the two is pain. One can lead into the other, and vice versa, much unlike how doping alone can get you 7 Tour de France wins, unlike what the USADA may believe.

The conventional rules of training are thrown out the window when the person says they have pain. Normal training would say to add load, through a full range of motion, and challenge the individual to complete the entire set with a metabolic response the coincides with their chosen goals. Pain says to move only within a pain-free range, with a sub-threshold load, and make the person feel better today, tomorrow, and the day after. Delayed muscle soreness is not something to go for. THis is why I say the window of movement capability is reduced, even if they have more movement available to them.

THis means we have to work from a neutral spine position, which is easier said than done. Getting someone in pain to move into a position that demands the core work differently than they feel it should, all while making sure they can breathe normally and not in a laboured or restricted manner means the devil is in the details. Getting someone into a neutral pelvic angle without a posterior or anterior tilt, getting them into a thoracic spine position that isn’t flexed forward, and having them open their ribs and diaphragm to get their breathing deep and solid, regardless of the position or exercise, can sometimes be all it takes to move from a bad exercise to a corrective exercise.

Take the most butchered of all exercises across the nation: the plank. I get a kick out of seeing plankers with their butts so high int he air they look like they’re auditioning for the next season of Jersey Shore, showcasing some exceptional lumbar extension capabilities and hip flexor stiffness, and all while reading the morning paper.

Neutral spine is a much much MUCH harder position to get into while holding a plank, which is why you never see it. By getting into a neutral spine and bracing so hard you feel like you’re going to create actual abs of steel from your gut, you should only be able to hold a plank solidly for about 10-15 seconds before fatigue-related compensations kick in. This isn’t just an observation, it’s science. McGill showed in Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance, a book I would highly recommend to any fitness professional or fitness enthusiast, that the longest duration one could typically hold a plank without seeing some form of deleterious compensation was a whopping 15 seconds. Less is more when training the core.

Once you can get neutral, breathing is necessary to get the entire core working properly. Bracing so hard your diaphragm can’t budge only makes you really good at bearing down and squeezing, not at making back pain feel better. Deep breathing also reduces fear and anxiety, which if done during a stressful exercise reduces the anxiety of the exercise, making it less painful.

Once the individual can operate pain free in a very small window, you can start to crack that window open a very small amount by including movements where the spine has to provide a small amount of movement and still have a high degree of stability, such as hip hinging, squatting, and any other compound ground reaction based exercise that sounds just plain awesome and fantastic.

Pain changes the rules, so knowing how to play the game makes a good trainer great. This was by far a very brief synopsis of what goes on during pain, and is in no way comprehensive. It does give an idea of why it’s important to have trainers work with those who specialize in painful clients and understand more about how to step back movements to reduce that window effectively. It’s great to come out with a new, sexy and intense exercise, but at the end of the day the goal should be to make people BETTER, however that may be interpreted by that individual. If this means bigger and stronger, or simply able to walk to work each morning without limping, that is the goal.

One Response to Windows of Movement