When is it okay to lift with less than perfect form?

Today’s guest post comes from Fayiz Dabdoub after a chance encounter he had with an online form coach who in spite of admitting to not being a coach, decided to critique one of his lifts. Hilarity as well as this post, ensued.

*****

If you’re reading this, then you probably care about getting stronger, building muscle, or both. Well, regardless of your goals, you’ll probably need to lift “heavy”. Heavy is a relative term. For example, a 400lbs bench is heavy for me but it would be a warm-up set for Dan Green.

When we reach a weight that one can lift for a maximum of one repetition, we call that our 1 rep max (1RM). This number can be used to determine how much weight a lifter might lift for his or her working sets during a given workout, assuming the lifter is using a percent-based program. For example, a lifter with a 400lbs bench press 1RM may work up to 320lbs for a top set of 5 reps at 80% of his or her 1RM.

Another way to determine the intensity (weight) of a lifter’s working sets is using a Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, typically scaled 1-10. For example, if a lifter can squat 450lbs no more than 8 times before failure, an RPE of 7 would mean the lifter did 5 reps with 3 left in reserve.

Now that we have some examples of how to determine what relatively heavy means, let’s talk about how forgetting about form while lifting heavy can HELP you and what brought this topic up.

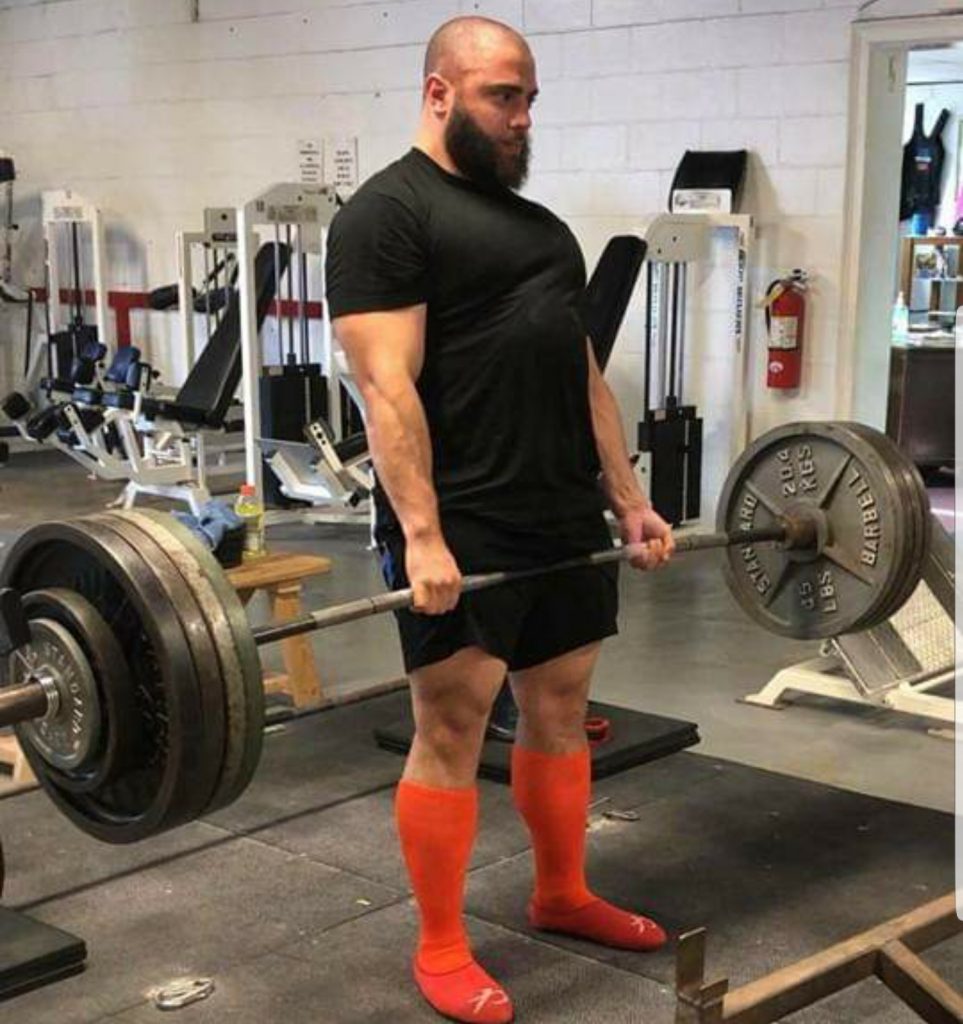

This topic came up after I posted a video of me squatting 480lbs for reps, when a stranger commented about my form. He went on about how I should widen my stance to reduce knee valgus (spooky!) that I had on the concentric phase of my squat. He proceeded to “help” me by telling me to squat low bar, although he didn’t provide any rationale for this suggestion. As well intentioned as his “advice” may have been, I decided to ignore it. Not because I think my squats are perfect, but because he decided he KNEW what I needed to do for a better squat, even though he admitted he has never coached a lifter before. He doesn’t know what my goals are, what my lifting history is, what previous injuries I may have had, or any pertinent information that a coach would need to know before giving advice to a lifter.

Do I think form/technique is important when lifting weights? Well, yes, to a degree. I mean, if you just go into the gym and start deadlifting heavy without decent technique, you may increase your risk for injury, right?

Well, not exactly. Injuries are caused by many factors and covering all of them is outside of the scope of this article.

My question is: how often do you see a lifter in a meet get injured, regardless of succeeding or failing the lift? Not as often as injuries experienced during training. Some of the more common injuries are due to over-use injuries, not the dreaded “butt-wink” or knee valgus some advanced lifters like Ben Pollack exhibit.

What if I told you what some people consider to be “bad form” is beneficial for the advanced lifter or that maybe the knee caving valgus maneuver helps the squatter lift more weight?

When you’ve been lifting for years and years, you see a few things that catch your eye. For example, the 700lbs squatter that leans forward and has knee valgus, the 800lbs deadlifter that rounds his back and so on.

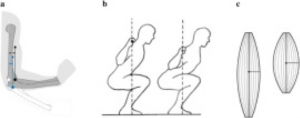

Why does this happen? Well, advanced lifters have become so adept at using their leverages to help them lift that extremely heavy load; they are able to use these deviations from textbook technique to their advantage. A squatter with extremely strong quadriceps will tend to valgus when the lifter needs that extra bit of boost to push through a specific range of motion (ROM) during the squat that would have been more difficult otherwise. We call this part of the ROM the “sticking point”. The “sticking point” is the joint angle in a ROM of any given lift that is the most difficult and is usually the point at which the lifter fails the lift. A squatter who needs to get deeper to get white lights for a powerlifting meet will exhibit what some think is “butt-wink”, but really isn’t. This advanced lifter is shifting their hips under a tiny bit to achieve this depth. Does this mean they’re going to blow their back out? Of course not! Our muscles are strongest at some joint angles and weaker at other points of the ROM and adjusting their technique to maximize their strengths through a specific joint angle is one adaptation seen in advanced lifters.

“… muscular torque can be affected by changing either (i) the force that the muscle produces, (ii) the angle between the direction of force and the distance from the point of interest (chosen centre of rotation) to the point at which the force is applied, and (iii) the point at which the force is applied.” (1)

So, obviously joint angle changes can affect the load lifted during an exercise. Advanced lifters take advantage of this by adapting their own version of what we would call “correct technique”.

“In particular, McLaughlin et al. examined kinematic characteristics of the squat performed by highly skilled powerlifters, and observed that the sticking point across the studied sample occurred at approximately a thigh angle relative to the ground of 30∘.” (1)

The authors went on to explain that specific torso angles would also affect where in the ROM a lifter might experience the sticking point, pointing out that there is no “correct” technique for everybody doing the squat exercise.

Included, is a video of a meet I competed in from August 2017. This was a PR at 260kg/572lbs and you can see what some would consider to be form break down, when the moving around helped me lift this weight up.

Leverages are HUGE, when it comes to lifting heavy weight and grinding through the sticking point. The advanced lifter gets to the high level they’re lifting at by learning how and when to use these variations in technique. This is done on purpose!

Now, I’m not saying proper technique isn’t important. There are certainly times when focusing on technique is more important than the weight being lifted.

- Learning a new exercise:

Beginners or advanced lifters learning new exercises should start with lighter weight to ensure they’re performing the exercise correctly. Not only will this reduce the likelihood of injuries as they progress, but it will help improve specific adaptations the lifter is training for.

Beginners get what is often called “newbie gains”. Basically, the beginner lifter has tremendous strength increases at the beginning due to improved neuromuscular activity. The firing rate increases, synchronization improves, and muscle fiber recruitment becomes more efficient.

- Hypertrophy and Strength phases:

Lifters going for muscle hypertrophy and strength should strive to lift weights through their entire range of motion. Pinto et al. state “The results indicated that elbow flexion 1RM significantly increased (p < 0.05) for the FULL (25.7 ± 9.6%) and PART groups (16.0 ± 6.7%) but not for the CON group (1.7 ± 5.5%). Also, FULL 1RM strength was significantly greater than the PART 1RM after the training period. Average elbow flexor MT significantly increased for both training groups (9.65 ± 4.4% for FULL and 7.83 ± 4.9 for PART). These data suggest that muscle strength and MT can be improved with both FULL and PART resistance training, but FULL may lead to greater strength gains.” (2)

Pinto and his colleagues found that full and partial ROM can increase both strength and hypertrophy but full ROM might lead to greater improvements in these adaptations.

- Previous injuries:

Lifters with a history of injuries might need to adjust their technique in order to lift pain free and to prevent injuring the site again.

- It is difficult to unlearn bad habits and easy to maintain good habits for lifting.

- All lifters have different physiological make-up (joint structure, bone structure, flexibility, etc.)

Bottom line:

- Techniques may vary from lifter to lifter depending on many factors (i.e. lifter experience, goals, injuries, physiological make-up)

- Advanced lifters are dialed into their bodies and can deviate from textbook technique when lifting max weight to help them overcome sticking points.

- Beginners and advanced lifters learning new exercises should start light with sound technique to reduce likelihood of injury.

- When lifting for strength and hypertrophy, full ROM might be better when the lifter is further out from a powerlifting meet.

- Lifters with previous injuries will need to adjust their technique to better suit their situation.

References

- Kompf, J., and Arandjelovic, O. (2016). The Sticking Point in the Bench Press, the Squat, and the Deadlift: Similarities and Differences, and Their Significance for Research and Practice. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.z.). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5357260/

- Pinto RS., (2012). Effect of range of motion on muscle strength and thickness J Strength Cond Res. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22027847

About the Author

Fayiz Dabdoub is an exercise physiologist from Atlanta, Ga that coaches powerlifters and high school football players. He’s been coaching for 6 years now and love helping powerlifters hit new PRs. He competes in USPA federation meets in Georgia, North and South Carolina and Tennessee. If you’d like to contact him for any questions or inquiries just click here