What’s Your Favourite Position

I’m really excited to bring you todays guest post from Travis Pollen, of FitnessPollenator.com. Not only is he a very smart and a great writer, but a very accomplished Paralympic athlete in swimming.

****

Let’s face it: asking someone to hang out in a deep squat for 10 minutes, although a realistic goal eventually, may seem like an impossibility at first.

Yet the ability to perform such a feat can radically improve not only movement quality, but also strength.

So what’s the secret? A re-conceptualization of movement into a combination of positions and transitions.

I recently had the opportunity to attend a workshop on “Positions and Transitions” by Dr. Chris Leib, physical therapist and owner of MovementProfessional, LLC. Over the span of just two hours, Dr. Leib blew my mind over and over again, painting a picture of movement like I’d never seen before.

Chris teaching a hollow body hold to an unsuspecting victim.

Many of us are probably familiar with the expression “train movements, not muscles.” This is the idea that the body works as one fluid unit, not as individual muscles. So instead of training “chest and triceps” or “back and biceps,” we can think of these exercises as “pushes” and “pulls,” respectively. This framework tends to afford us more balance in our training.

According to Dr. Leib, though, prior to movement we must first consider position. You see, at the most basic level, movement can be broken down into two simple components:

MOVEMENT = POSITIONS + TRANSTIONS

Positions are ‘static postures,’ and transitions are ‘the changes in orientation of the body from one position to the next.’

This notion is steeply rooted in the traditions of both Olympic weightlifting and dance, where position is considered

- “A place to linger, a pause on a journey”

- “A snapshot in time”

- “A staging point for movement”

(Source: http://www.healingdance.org/uploads/3/0/9/5/30953171/flow_movement_position_and_transition.pdf)

Ballet positions one through five.

Thus, in order to move optimally, we must first be able to assume the requisite positions of our target movements. If one or more positions are faulty, then no matter how seamless the transitions, the quality of that movement will suffer.

From a performance standpoint, the greater ease with which we can achieve a position — even completely unloaded — the more efficient we’ll be as the weight gets heavier.

Poor Position Dooms Movement

It’s much easier to engage the appropriate muscles during a static posture than it is in the heat of a transition. Take the deadlift for example. Suppose a lifter’s abs and glutes are inactive (resulting in excessive anterior pelvic tilt) at the start of the deadlift. What do you think will happen as the lifter transitions to the lockout position?

Overly arched back deadlift

Chances are good their abs and glutes won’t just kick on all of a sudden. What’s more likely is that the lifter will remain short through the front of the hips, substituting low back extension for hip extension. They’ll then compensate even further by leaning back at lockout, thereby stressing unintended passive structures of their low back.

Were the lifter to have engaged the abs and glutes properly from the start position, they would have been far more likely to continue to use their glutes to extend through their hips during the transition and into the lockout position.

Position Playbook

The human body has the ability to assume a vast array of positions (if you know what I mean!).

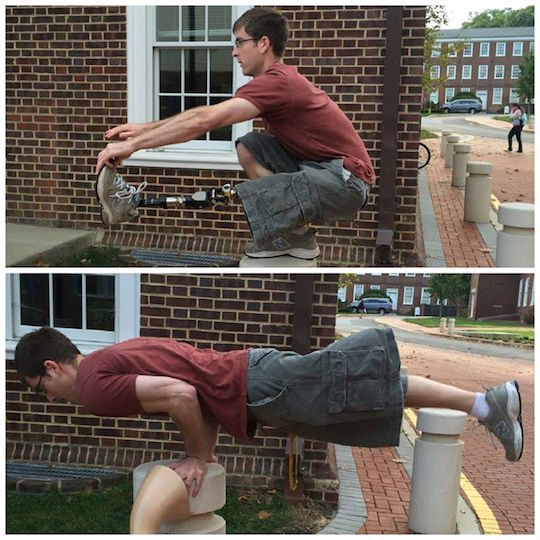

Here I am showing off a couple of razzle-dazzle positions.

For now, though, let’s just consider five basic sagittal plane ones:

- Overhead (examples: bottom of chin-up, top of overhead press)

- Front Rack (examples: front squat, top of clean)

- Hang (examples: bottom of hang snatch, top of deadlift)

- Hip Hinge (examples: bottom of deadlift, bottom of swing)

- Squat (examples: bottom of back squat, bottom of squat clean)

Fascinatingly, these positions resemble one another far more than they differ. Beginning from the core and extending outwards, each position requires the following cues:

- “Brace the abs” (by pulling the ribs down)

- “Brace the glutes” (by subtly externally rotating the hips)

- “Push all four corners of the feet into the ground”

- “Elongate the neck”

An exception to Cue #3 will of course be if the feet are off the ground, as in vertical pulling positions. In this case, we’ll push just our toes down towards the ground.

From there, it’s just a matter of adding in one or two more cues for each position:

- Overhead: “arms in line with ears,” “thumbs back”

- Front Rack: “tension in armpits” (by engaging the lats)

- Hang: “tension in armpits” (by engaging the lats)

- Hip Hinge: “flat back,” “knees slightly bent”

- Squat: “chest up,” “knees in line with middle toe”

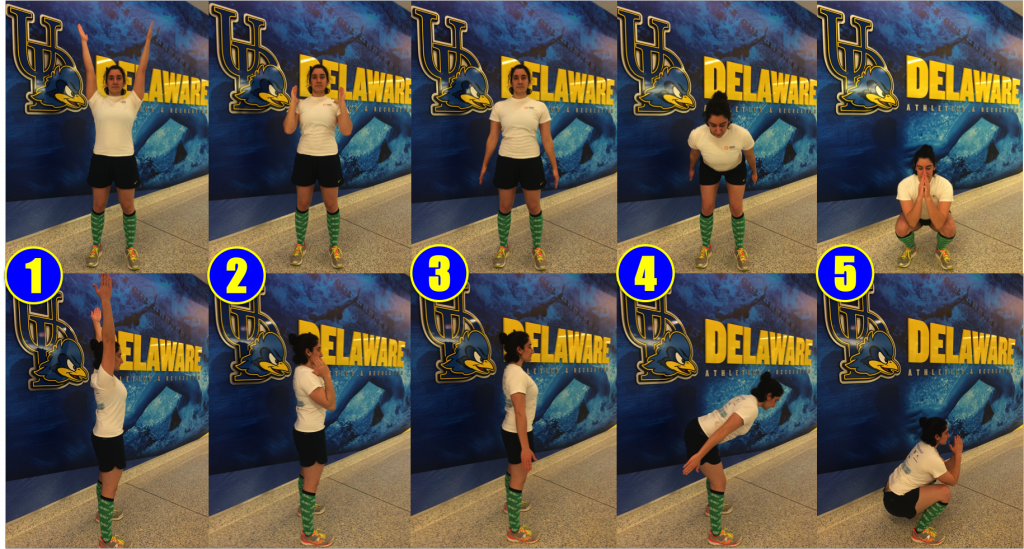

Ana demonstrating the Position Playbook in stunning fashion.

Common Breakdowns in Position

Unfortunately, most of us don’t have perfect posture in these positions. Just about everyone has a position (or five) that needs improvement.

Here are a few of the most common breakdowns:

- Overhead: incomplete shoulder range of motion, compensation through shrugged shoulders, forward head, overly arched back and neck

- Front Rack: winged elbows, excessive anterior pelvic tilt, overly arched back

- Hang: rounded shoulders, excessive anterior pelvic tilt, overly arched back

- Hip Hinge: straight legs, overly arched neck, round back; or excessive anterior pelvic tilt and overly arched back

- Squat: collapsed feet, knock knees, butt wink, round back

Ana demonstrating common breakdowns in each position.

If the fault is due to a simple lack of awareness, just re-cueing it (i.e. “Knees out” or “Chest up”) can lead to instant improvement.

Other times, the transitions between positions may just be occurring too quickly in an exercise, as in a kettlebell swing, for instance. In this case, a few more weeks spent solidifying positions via a slower tempo kettlebell deadlift will clean those positions right up.

When Cueing or Regressing Doesn’t Do the Trick

Sometimes, however, there’s no quick fix. Whether it’s due to lifestyle, previous injury, or perhaps even kinesiophobia (fear of movement), our ability to achieve a good position can become impeded.

Perhaps two segments, like the pelvis and hips, are unable to dissociate (move independently of one another), as in the case of the earlier deadlift example where excessive anterior pelvic tilt and hyperextension of the lower back masqueraded as true hip extension.

To address this dysfunction, we must work on mobility, which is our ability to actively move our joints through their full ranges of motion. Increased mobility (to the proper degree) means increased comfort in tough positions.

Mobility tools like superbands for joints and lacrosse balls and foam rollers for soft tissue are the perfect self-help solutions – not to mention a lot cheaper than several visits to a manual therapist.

These tools can also be used anytime: right after rolling out of bed, before or after training, and before going to sleep (to down-regulate the central nervous system). Plus, taking charge of our own mobility issues increases body awareness and is incredibly empowering.

Many volumes have been devoted to specific mobility drills. One of the best resources on the market is Dean’s Ruthless Mobility. Get it, identify your problem spots, and stick with the corrections for several weeks.

If It’s Not Mobility, Then It’s Stability

Poor position can also be tied to a lack of stability, which results in a suboptimal division of labor between our deep and superficial muscles.

Deep muscles lie close to the skeleton. These muscles stabilize the body against unwanted motion and are fatigue-resistant (i.e. designed for low-intensity, long-duration holds). Superficial muscles lie closer to the surface of the body. These are our “prime movers” and tend to fatigue more quickly (i.e. designed for moving big weight).

If the deep muscles fail to fire adequately in a given position, the superficial muscles are forced to fill in as stabilizers, which then detracts from their torque producing capabilities during the transitions between positions.

Training Positions Through Static Holds

Once mobility work has been taken care of, static holds are the best way to make those mobility changes stick as well as promote the proper division of labor between the deep and superficial muscles.

By training static holds, we improve our ability to fire our deep, fatigue-resistant stabilizing muscles, which in turn allows our superficial muscles to kick in at full tilt when called upon during a transition.

Below are my favorites holds for improved comfort, strength, and automaticity in each position. Use them immediately following mobility work and dynamic warm-up.

- Overhead: overhead barbell hold, active straight-arm hang

- Front rack: bottom’s up kettlebell waiter’s hold, neutral grip bent-arm hang

- Hang: dumbbell farmer’s hold, paused barbell deadlift at lockout

- Hip hinge: paused barbell deadlift just off the floor or below the knee

- Squat: deep squat hold with or without kettlebell counterbalance

Ana demonstrating static holds for each of the five playbook positions.

Remember, we don’t want these holds to feel like all-out one-rep max attempts. Instead, the objective is to assume the positions with minimal effort and relaxed breathing. In fact, a goal of eventually holding a deep squat for ten minutes with ease should not be out of the question.

Start off with short duration repeats (i.e. 3 sets of 3 reps of 10-second holds) with light loads. Even just a dowel rod can induce some serious muscle quaking in the paused deadlift positions. Progress by increasing hold duration, number of repeats, or load.

Beyond the Playbook

The idea of position extends far beyond the five discussed above. Frontal and transverse plane movements all have their own unique positions, as do supported and unsupported unilateral stances.

In terms of the Olympic lifts alone, there’s the top of the high pull, or “scarecrow” position, that occurs immediately prior to dropping underneath the bar, as well as the split-stance catch position (as in a split jerk).

Perfecting the playbook positions first, though, makes the progression to other planes and one-sided stances markedly smoother. And of course, beyond positions, there are also transitions. But these are subjects for another day.

Special thanks to Dr. Chris Leib for his inspiring development of this topic, Ashley Barnas for the stunning photos, and Ana Ebrahimi for her flawless positioning.

About the Author

Travis Pollen is an NPTI certified personal trainer and American record-holding Paralympic swimmer. He is currently pursuing his Master’s degree in Biomechanics and Movement Science at the University of Delaware. He maintains a fitness blog and posts videos of his “feats of strength” on his website, www.fitnesspollenator.com. Be sure to like him on Facebook at www.facebook.com/fitnesspollenator.

5 Responses to What’s Your Favourite Position