What Kathy Bates Taught me About Ankle Mobility

Today’s guest post is from Michael Dennison, a yoga instructor with a niche in training runners, who tend to need all the help they can get when it comes to flexibility. Having sustained a few ankle injuries in my day, I can attest to how important ankle flexibility can be, and really appreciate him contributing a great article today.

Whenever I think of ankles, I think of Misery. It was 1990, and the movie based on Stephen King’s novel Misery had just been released. It starred James Caan as an acclaimed novelist and Kathy Bates as a nurse who cares for him after he is seriously injured in a car crash near her isolated, snowbound house.

As the bedridden Caan recuperates in her house, he (along with the audience) begins to realize that Bates is kind of . . . um . . . off. Well, not just kind of off, very off. Despite the fact that Bates’s nurse character is a huge fan of Caan’s writer character, she takes issue with the plot line in his new novel, and, well, at that point things pretty much go south for Caan. Sensing that something is amiss with Bates, he uses her absence from the house to leave his sick bed and roam the house in a wheelchair, plotting an escape. Oops, bad move. Bates returns, cottons on to his unauthorized wandering, and decides a preventative measure is warranted to ensure this behavior is not repeated. So she does what any demented caregiver would do: with Caan now tied to the bed, she grabs a sledgehammer and breaks his ankles. Yes, both ankles . . . with the sledgehammer. Need I emphasize that these are not light taps she administers, but a full wind-up? I think you get the picture.

There’s little doubt that in the annals of movie sadism Bates’s “hobbling” of Caan ranks near the top of any list of non-gratuitous, ghastly acts. As to the audience’s reaction, 23 years has done little to diminish the freshness of my memory of that moment. The collective gasp, muffled screams, and “oh my Gods” still ring clearly today.

But as macabre a story as Misery was, I like to think of Nurse Bates less as a destroying angel and more as a symbol of what awaits runners if they lose the range of motion (ROM) in their ankles. The demon image of Bates looming over us haunts our sleep like a perpetual nightmare. There she stands, smiling grotesquely, sledgehammer slung over her shoulder, preparing to dispense her own brand of therapy as you lie tied to your bed, mouth open but unable to scream.

When we consider the ankle joint, we see that an important requirement for its proper functioning is a high degree of mobility in the sagittal (forward and back) plane. This mobility is demonstrated by the ability to dorsi-flex (bring the top of the foot, or dorsum, closer to the shin bone, or tibia) and plantar-flex (point the foot and toes) the foot. With the bare foot flat on the floor and the heel grounded, we should be able to move the knee forward over the toes, reducing the 90-degree angle between the tibia and foot by at least 20 degrees. But runners with poor ankle mobility can barely dorsi-flex their foot/ankle, almost as if the shinbone and top of the foot are frozen into a right angle.

Unless it’s the ankle itself that’s been injured, it’s usually starved for attention. Unlike the knee, with its diva-like needs and neuroses, and the depressive foot, with its fallen arches and calloused skin, the ankle tends to linger in obscurity, unloved and easily overlooked as we rush our attention back and forth between the knee and the foot. Part of the problem is that most runners are clueless as to the true source of their pain and dysfunction. This is because pain can be a terrible liar, and has a way of manifesting where the real problem isn’t. The compensatory tricks the body employs to move around the ankle’s limited mobility are devilishly effective, but the results of that compensation are pernicious.

This is because the body plays a kind of zero-sum game, and at some point the ankle will reclaim its lost range of motion from elsewhere in the body. When we walk or run with tight ankles the body searches for the lost mobility by initiating a series of compensatory actions, and this is where the problems really begin. What’s so perplexing is that runners won’t necessarily feel this limited mobility. Instead, they’ll experience the effects of the compensations: collapsed arches, bunions or hyper-pronation in the feet, anterior knee pain, various problems in the hips, or low back pain.

There are several ways mobility in the ankle joint can be compromised. The first is as a result of injury. If the ankle has been sprained or broken, scar tissue or impingements can impair its ability to move freely, reducing range of motion.

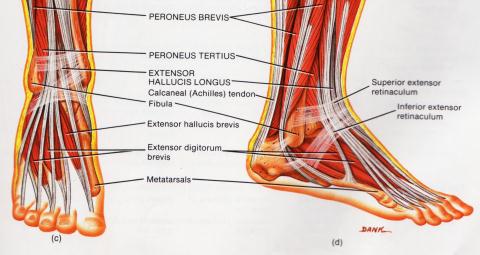

Ankle mobility can also be reduced if the tissue in the back of the lower leg is tight. The structures that can become very short and tight, thereby reducing mobility, include the Achilles tendon, gastrocnemius (calf), soleus, and posterior tibialis.

Finally, choice of footwear can affect the ankle’s ROM. Our favorite sport (or sports) may require footwear that allows the ankle little or no movement. Downhill ski boots, hockey skates, and high-top basketball sneakers are examples of footwear that can limit ankle mobility. Also, habitually wearing shoes with high or stacked heels will shorten the tissue in the back of the lower leg, limiting dorsi-flexion.

That I stress the importance of ankle mobility in my runner’s yoga classes and workshops shouldn’t be a surprise. In class, people with tight ankles are easy to spot. As they sit in any posture that requires substantial plantar flexion of the foot (Virasana, for example: see photo), they’re the ones who have difficulty keeping their ankles and feet straight. One of the body’s tricks is that it will try to move around areas of stiffness, so if the ankles are tight they will crescent outwards to avoid the restriction and find room to move. When I see “bowed” ankles, I reposition them to be sure they’re straight. This way they’re moving into the stiffness and not around it.

Outside of yoga class, another tight ankle “tell” is a bouncy stride. As we run, the main direction of movement should be forward, with slight up and down motion. But the runner with ankle mobility issues avoids the restriction by lifting their heel of the ground prematurely at the end of the stance phase. This action sends them “up” instead of forward, wasting substantial energy and shifting the mobility emphasis from the ankle to the forefoot. The calves and other posterior structures of the lower leg are now being used to push them through the gait cycle. Runners with this type of gait pattern are referred to as “quad dominant”, because rather than using the powerful gluteus maximus (buttock) muscles, they extend through the quads and calves.

If there’s any lesson to be learned from Misery, it’s to keep your ankles mobile and avoid the problems that poor ROM creates. For added incentive, rent the movie. Think of it as Nurse Bates making a house call.

If you laughed yourself sick when you read this, then you’ll get sick again if you miss my courses in Calgary, Halifax and Vancouver. Check my schedule at and sign up soon: www.mikedennisonyoga.com

7 Responses to What Kathy Bates Taught me About Ankle Mobility