Symmetry Doesn’t Even Matter, And Probably Causes More Problems Than It Solves

One of the key takeaways I want people who’ve attended any of my workshops to go home with is the fact that everyone they work with is an individual who has their own anatomy, strengths, weaknesses and goals, and as such, will approach a lot of exercises in their own unique way that may not look like the textbook definition. I’ll repeat the term “n=1” a lot, because each choice a trainer makes about a training program, exercise, or even approach to the same exercise, is going to be dictated by the person in front of them and their individual differences.

A lot of the research on anatomical variance can show that some people have structures that can really easily allow specific movements, whereas others would have an easier time of taking down a brick wall with only their upper lip than say, squatting to depth, regardless of how much mobility work or soft tissue smashing they do. Their joints just don’t do that thing.

And even looking deeper down the anatomy rabbit hole, there can be a significant difference between your left and right limb, especially if you played a one-sided sport as a kid.

Baseball players will have their throwing arms humeral head deform to allow a greater layback position to put some spicy mustard on their fastball, which isn’t seen in their non-throwing arm.

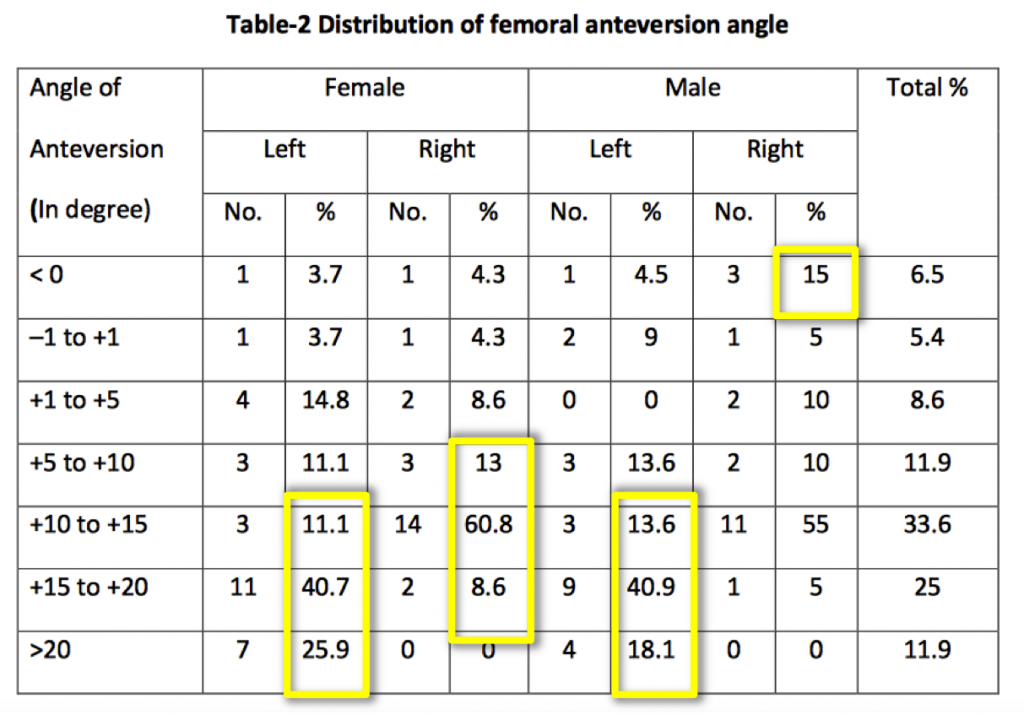

Hockey players, who always stand with one hand lower on their stick and somewhat twisted, will have an easier time turning to the elevated hand side, and will have better hip extension on that side compared to the other. When looking at differences in femoral neck angle of left and right leg in kids with cerebral palsy, Davids et al (2002) showed that in some kids it can be as small as just a few degrees to more than 25 degrees. This structural difference could mean one foot turns out while the other turns in, due entirely to the geometry of the joints.

Zalawadia et al (2010) even showed in people without cerebral palsy that there could be a significant difference in anteversion angle between an individuals’ left and right leg, in some instances up to 20 degrees or more in asymptomatic individuals. That’s just how they’re built.

So if there can be a significant difference in the structure of the individual in front of you between their left and right limb, trying to get to the textbook definition of symmetric may not be possible, or even beneficial.

Consider it this way. If I want to stand with my right toe turned out because of a structural hip variant that is different in my right leg than my left, the muscles of my hips are still relatively balanced in terms of the tension they exert around the joint at rest. If I try to stand in a symmetric stance, I’m rotating that right toe in, which now creates an altered tension around the joint compared to letting it turn out. This tension on the right hip is different than on the left hip, both at rest or during any exercise I would want to do in that stance.

While we may want to get to a stance that looks something like this during our squats or deadlifts:

It may not work at all for the individual in front of you at the moment for all of the reasons outlined above. A reasonable hypothesis that could easily be tested would be if they do have any kind of asymmetric structure, they should take some type of an asymmetric stance, which would likely feel significantly more natural and comfortable for them than the symmetric stance. This may mean they have to turn one foot out further than the other:

They may also have to have one foot slightly behind the other, whether the foot is turned out or not:

They may also benefit from not having both feet flat on the floor, so moving into more of a split squat or lunge type position may be more valuable than a flat footed stance.

Are any of these positions “wrong?” No. One may be entirely right for someone, but not work at all for someone else. That’s fine. We don’t all need to do the same things, like the same music, or move the same way.

A good analogy to think of with this kind of asymmetry is when you go to the optometrist to have your vision tested. They’ll flip the little lenses back and forth in front of each eye to see which one you feel you see the best with, and write up specific prescriptions for each eye. Those prescriptions can be significantly different from one eye to the next, so your arms and legs having different “positioning prescriptions” shouldn’t seem unusual in that context.

Some people may respond incredibly well to a small tweak to their positioning on a movement like a squat or a deadlift. Others may not notice anything. Play with your positioning to find out what feels strongest and most stable for you, and train that positioning. Include some other exercises and positions to help get some variety in different set ups and alignments so you aren’t just existing in one set pattern, and enjoy the process.

For more info on how to tell specific anatomical differences like this, plus how to tune a stance to take advantage of the individuals unique structure, check out Even More Complete Shoulder and Hip Blueprint with Tony Gentilcore and myself. This video series digs deep into anatomy and training elements, plus comes with continuing education credits.

The series is currently on sale for $60 off the single item, and $100 off the combo pack with both level 1 and 2 content. The combo pack contains 22 hours of digital video content combined. We also included 4 month financing options for both the single item and combo pack, at no additional charge. The sale ends April 5th at midnight est, so act quick and get your copy today!

Click HERE for more info

Here’s a sample of some concepts we dig into.

Shoulder:

- How to use the static and integrative assessments to guide your training program.

- How breathing mechanics drives mobility of the upper body and stability of the lower body, and how to use it to see fast improvements in both.

- neck positioning, sternoclavicular joint, and elbow considerations with shoulder movements

- Deeper assessment considerations, including medical elements that may require a referral for non-fitness modalities

- Why “impingement” and “scapular winging” are garbage terms, how to assess for their true function and purpose, the difference between internal and external impingement, and what it means to your training program

- How simplifying your upper extremity assessment to the “Big 3” – Release, Position, Mobilize – can and will cover your bases for most shoulder ailments.

- Heavy pressing, explosive throwing, and programming considerations for different goal sets and populations

Why this matters to you:

- Help your clients get through common shoulder issues more effectively.

- Streamline your assessment and program design, helping you get faster results and more efficient use of your time, and that of your clients’

- Help you see the details of shoulder motion you didn’t notice before, and whether something you’re using in your exercise program is working or not. Plus look at whether neck or clavicular issues may be impeding their strength and mobility.

- Upgrade your exercise toolbox to address commonly overlooked movement issues

- Smash programming like a Jedi

Hip:

- The hips role in low back, SI joint, and knee issues commonly seen in the gym, and how to address them from a fitness perspective

- Static versus active mobility, how and when to use each, and what produces the best benefits

- Scaling compound lifts across populations and goals, and how to effectively program them for everyone

- Jumps, sprints, change of direction, and other explosive training elements, and how they relate to the individuals goals and abilities.

- Blending strength, mobility and recovery across age ranges, and how to avoid being a beat up meathead or chronic recoverer

- spinal motion intolerances, and how to program around common issues.

What this means to you:

- You can help clients see IMMEDIATE improvements, sometimes in as little as a minute or two, which will help them buy in to your abilities.

- Help you target in on what will work best for the person in front of you, saving you both the time spent on useless exercises or drills.

- Help clients get specific with what will help them get stronger, more mobile, and faster than ever before

- Break down a system you can use today with yourself or your clients to see instant benefit while removing the guess work.

To show how awesome this series is, we even have a few short clips from the series that you can watch for free.

The sale ends April 5th at midnight est, so act quick and get your copy today!

Click HERE for more info

*Not an actual guarantee, but wouldn’t it be awesome if that happened?

3 Responses to Symmetry Doesn’t Even Matter, And Probably Causes More Problems Than It Solves