The Side Plank for Internal Rotation Question, Answered

About 15 months ago, I wrote an article for T-Nation on how stretching doesn’t work, and gave some examples of better ways to improve mobility, as well as how to see longer term improvements compared to static stretching.

One aspect of the article that garnered a lot of attention was a short video clip I inserted from a recent Spinal Health and Core Training workshop hosted with myself, Rick Kaselj, Tony Gentilcore and Jeff Cubos. The clip showed me taking a woman through a short and simple assessment for some hip restrictions and common complaints of “stiffness” as well as some low grade undiagnosed back pain. It wasn’t anything ground breaking, just range of motion testing in both gross and joint-specific movements. The involvement of the test-intervention-retest seemed to show some good benefits.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=2fzDw-vgQZ4%3Ffs%3D1

The response to this video in the article was phenomenal, and I was really happy to see so many people enjoyed it and got so much from watching it.

Since then, I’ve had probably 4 or 5 emails or Facebook messages a week asking for an explanation on how it worked and whether it was just a magic trick, photoshop, or whether there was an actual reason for the hip rotation to improve with something as simple as a side plank and not moving the hip through any kind of range of motion.

I thought in the interest of saving myself a lot of time and also to help those who have emailed me in the past as well as those who will either attempt to email me or are too scared to reach out (I don’t bite, promise), I thought I would outline the entire thought process here in todays post. For those of you with any fears of geek talk, this could get intense. For those who enjoy geek talk, you may need to get some popcorn and change into some sweat pants to accommodate your, *ahem* excitement.

Background Theory – Neurological Muscular Drive

Here’s the funny thing about muscles: they’re pretty stupid. They only do what they’re told to, and don’t put up much of an argument. The nervous system says to contract and they contract. It says to relax, they relax. If no signal gets through, as in a spinal chord injury, they don’t do anything. The will respond to spinal reflex loops where there’s stimulation of a neural receptor that says contract, like in a golgi tendon organ stimulation, or when pulling your hand off a hot stove, but for the most part, it’s the brain controlling things.

This is apparent after a seminal study by Bennet et al (2009) where they tested the knee range of motion before and after sedation with a spinal nerve block as the patient was getting ready for a total knee replacement. The pre-sedation measurement was the available range of motion before pain or tissue guarding became the limiting factor, whereas the post-sedation measurement was the available range of motion without pain or guarding being an issue.

Passive flexion increased an average of 16.4 degrees, while passive extension increased an average of 3.0 degrees for a total increase if 19.4 degrees, without altering the tissues themselves.

Had this been a case where “adhesions” or “scar tissue” or other forms of mechanical or structural restrictions were the cause of the reduced range of motion, removing the neural impulse into the tissues wouldn’t have had the same effect as the limiting factors would still be there. This isn’t to say those aren’t potential limiting factors, but that there’s more to it than simply looking at structure or adhesive limitations alone.

The body will limit movement into ranges of motion that it deems to be either risky, pain-producing, or simply unknown. This is evident with people who approach new movements and have no frame of reference. A classic example is a simple box jump. Many people approach the first rep of even the lowest box height with trepidation and hesitancy, fearing the worse. Once the first rep is complete, they can usually bang out more like nothing, until they get into a mental block and again have issues getting through the movement due to fear.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Cr_rNGvC46Q%3Ffs%3D1

The body will always subconsciously protect you from your own best intentions, at least as much as you’re willing to listen to it. Occasionally it has to create protective tension through an area to help support an injured area, or in response to increased loading from less than ideal body positioning, or potentially to take up slack for an adjoining area that it perceives to not have enough stability to be in a protected state.

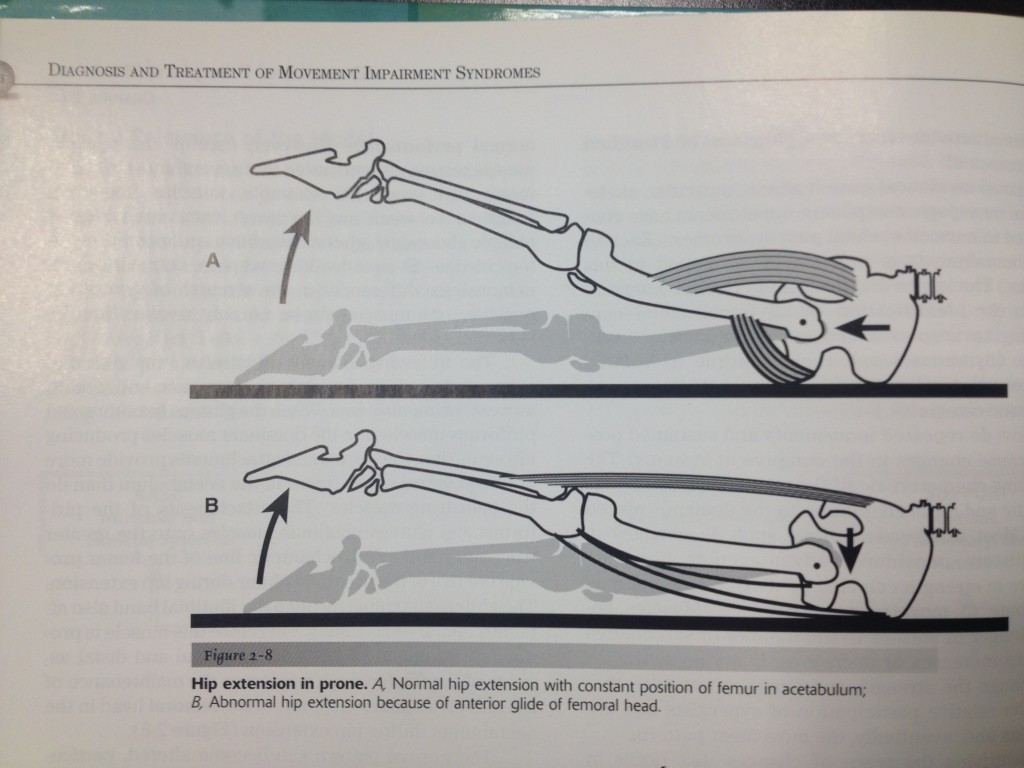

Specifically relating to the hip, this could be a centration issue where the body is resisting forces acting to alter the joint position of the hip, especially in a state where the glutes are less active than the hamstrings or low back in hip extension based movements. If the femoral head is consistently being pushed forward by the action of the hamstrings on the joint, the internal rotation function of the psoas, adductors, glutes as well as a bunch of others I can’t think of right now, will be kicked up to resist further forward glide, and will therefore reduce internal rotation through passive motion.

With reduced stability, the body will find it elsewhere to prevent damage, usually by robbing another segment – tweet that

Couple this with the fact that many people tend to have less than optimal core strength or stability, and find stability through hanging into either hard anterior pelvic tilt or T-L extension, and the hips work hard to prevent further internal rotation collapse through basic stance or walking. Plus, people have a propensity to value fashion over function when it comes to footwear, and we also walk on either flat hard surfaces or slightly cambered streets to allow drainage and you have a recipe for the internal rotators working overtime to try to keep you from falling over.

Then there’s people like this, who should just give their head a shake.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=VmZ7Do0gbCU%3Ffs%3D1

This position also tends to limit the active straight leg raise test, which is meant to talk about flexion-based strength and stability in balance with posterior chain flexibility. There’s many times where a reduced active straight leg raise can be passed with passive mobility due to a reduce impulse to the flexors to raise the leg, even though everyone seems to think it only looks at hamstrings.

I had a chance to work with the Edmonton Oilers last year with FMS testing, and found that even though the goalies had the ability to hit the splits in multiple positions, lead legs, etc, they had some mild to moderate restrictions with the active straight leg raise. They’re used to dropping into the splits, which means they didn’t have to raise their legs very much, just give enough of an impulse to pull down. Raising the leg was a movement they never really did, and after standing in a butterfly stance each and every practice, they had some issues overcoming their adaptations.

A poor active straight leg raise could also be indicative of femoral anterior glide, as mentioned in the earlier segment talking about the hamstring versus glute dominant extension. If the femur is gliding forward, there may be some pinching of the structures of the anterior hip, which would limit further movement. They may be able to get through this by externally rotating the leg being raised or turning the foot out of the leg still on the ground. This reduces compressive action on the anterior femur, which is a nice little cheat and helps move without pain, but sucks donkey balls for helping you to figure out the problem.

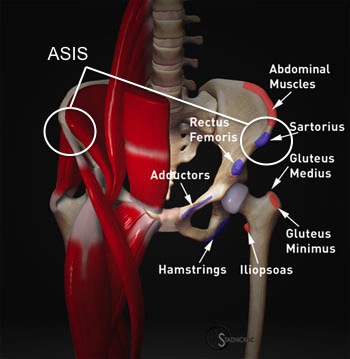

A lot of the structures involved with anterior femoral glide tend to converge around the anterior superior iliac spine, or ASIS. THis is a common zone of apposition, which means a lot of stuff attaches or passed over it, and can make a problem with one muscle or another look like a problem with a completely different muscle in the same area, simply because they attach to the same place and influence each other quite a bit.

Additional to the muscles listed here are the abdominal internal and external obliques, fibers of the transverse, and fascial sheaths that invaginate directly with the quadratus and multifidus muscles. This means there’s a direct correlation to disturbances with the hip relating into core function and vice versa.

Additional to the muscles listed here are the abdominal internal and external obliques, fibers of the transverse, and fascial sheaths that invaginate directly with the quadratus and multifidus muscles. This means there’s a direct correlation to disturbances with the hip relating into core function and vice versa.

The relationship to core function and breathing is also incredibly integral, as discussed in THIS POST on the diaphragm. The impact of breathing on core function is also magnified by the ideology that impaired deep breathing can cause an excitatory response to the autonomic nervous system, making it less likely that you will get relaxation of the over-tensed and chronically engaged muscles. That, and anatomically the diaphragm directly links into the psoas, pelvic floor, quadratus lumborum, obliques, and a good chunk of the muscles that would have some impact on hip rotation capacity.

There’s a lot of links to hip rotation that initiate in the core, as discussed above. I would be remiss to not mention the role of the lower body in hip rotation position, specifically how foot pronation can lead to internal rotation, but that could be a topic for another blog and has nothing to do with the side plank shown, so I’ll try to keep this all somewhat brief and gloss over it. I will say it’s important, but we won’t talk about it today.

The reduction in hip internal rotation is merely a symptom of something else not working properly. Because of this, we could stretch it as much as we like and never see any difference. As a result, we have a generation of people focused on the kinesiology of “stretch the tight” without asking the best question possible: why is it tight in the first place? Muscles don’t just get tight on their own, they’re told to be tight. Figuring out the why helps to target in on the reason, which will help to give better results than simply banging your head against a wall and wondering why your headache doesn’t go away.

Stretching plays a role to help reduce neural drive to a muscle and overcome the protective mechanisms causing a muscle to be tense. However, it doesn’t address the cause of the muscle being tense in the first place. If the muscle is sore from a previous hard workout, stretching will help restore sarcomeric gliding, but length changes will be difficult to see.

If the muscle is tense because it’s protecting a perceived instability, compensating for another area of the body that isn’t generating enough tension to stabilize an area, or is guarding against a perceived threat, it will maintain tension until any or all of these 3 scenarios are remedied.

Because of this, a simple stabilizing movement such as a side plank can have a massive impetus to promote stability, co-contraction from multiple segments, and reduce the perceived threat to injury due to the up-regulation of other muscles that contribute to the motion.

The correlation I have found that works most effectively is as follows:

- hip internal rotation impairment correlates to lateral stabilization

- hip external rotation impairment correlates to anterior stabilization

This means that doing a lateral stability exercise such as a side plank, suitcase carry, crossover stride sled pull, or anything else where the spine is being exposed to a lateral flexion force it has to resist, tends to impact hip internal rotation in a positive manner.

An anterior stability exercise (specifically anti-extension based exercises) such as a front plank, ab wheel rollout, supine leg raise, or anti-extension cable press tends to impact hip external rotation in a positive manner.

My Thoughts on These Concepts

From my experience, the core function directly impacts hip function, and vice versa. Breathing plays a big role in this, so tensed and halting breathing will negatively impact the effects of the core exercises compared to deep powerful and full breathing using the diaphragm instead of apical breathing. Positional stability and responsiveness to external stimuli and internal hesitations with novel or possibly dangerous movements can be overcome with pre-activation of stabilization movements to engage more supportive musculature, and once novel situations aren’t novel anymore, the guarding response is reduced, especially if there were no adverse effects of the movement.

A 10 second plank, done for 3 or 4 reps, produces much better benefits compared to a 30 or 40 second constant hold when it comes to increased hip mobility and core function. When the core is trying to fire up, fatigue can play a big factor, so breaking a set up into multiple short “reps” can make a big difference in how the set can be performed. The key is getting into and maintaining a neutral posture where the spine, hips, and legs are linear, not arched or drooping. Common compensations are shrugging the ribs up, shrugging the hips up, rolling the shoulders or hips forward, or pretty much anything that’s not neutral.

When in a neutral alignment, focus on deep, full, powerful breaths, where exhalations are strong and focus on abdominal contractions to squeeze the air out, but only while able to maintain neutral.

You can test this on yourself if you like. Do a seated hip rotation test and see how each leg responds. Without lifting either sit bone off the surface, ideally you should be able to actively get to roughly 45 degrees external rotation (foot coming closer to the midline) and about 20-30 degrees internal rotation (foot moving further from the midline). without passive assistance. If you find one direction is impaired, hit up the desired pattern: front plank for reduced external rotation, side plank for internal rotation. Get linear, do 5 deep full breaths without breaking form, and then re-test the area to see if it improved. If not, it could be more of a structural or alignment issue causing the restriction, but that’s typically something I’ve only seen in about 25% of people with a restriction.

I’m sure there’s other explanations for how these occur, and I’m definitely not the smartest person on the internet, so if there’s a salient explanation other than the one I’ve presented here, I’d love to hear it. The good thing about being wrong is if I see evidence of a better way, I can change my stance and be right again. Chime in and let me know what you think by dropping a comment below.

33 Responses to The Side Plank for Internal Rotation Question, Answered