Random Thoughts on Fatigue and Training to Failure

There’s a time and place for everything in the training world. There’s a great quote, I think attributed to Dan John, and paraphrasing, “Everything works, until it doesn’t.”

You can gain muscle with bodyweight, high reps, heavy weights, twice a week training or 6 times a week.

You can lose bodyfat with a caloric deficit, either through dietary modifications, increased activity, both, or any combination of factors.

You can use dumbbells, cables, barbells, bands, shakeweights, bosus, whatever floats your boat, and it will all provide SOME benefits.

There’s always going to be times where certain approaches are more beneficial than others, and some tools that have higher utility than others.

Training to failure is one such approach. It’s a common technique in bodybuilding worlds. Do as many reps as you can at a given weight, until you can’t physically complete another rep. Die a little on the inside, breathe out your soul, and then repeat. You stress the muscles enough to force it out of homeostasis and cause some sick gainz. Lather, rinse, repeat.

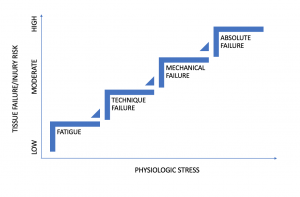

This is one type of failure in terms of the exercise world, and today I wanted to outline a few different types, where they exist, who should use them, and when to kick them to the curb. I even made this sick graph.

So let’s start with the basics. As you do any kind of workouts, you’ll start to become a bit tired. This fatigue can shift some physiological factors, such as blood glucose, neuromuscular coordination, pH inside the muscle, stuff that makes continuing on a bit more challenging. This won’t directly affect the execution of the exercise itself as long as the intensity is relatively low and recovery is appropriate.

As you go up the chain, technique failure can happen with these fatigue changes. Imagine setting up for a deadlift. The first 3 reps are crisp and perfect, but then on the fourth, your low back can’t lock in and you start flexing a bit. You can still complete the rep, but the technical elements aren’t all holding together. The weight isn’t too heavy to move, but you’re going from 100% perfect assigned technique to 70 or 80% of all the checkmarks.

This technical failure means you’re no longer doing the exercise the way it was outlined. You’re likely getting less of the benefits of the movement and more of the risks than prescribed, and often this is where the set is stopped. Even if you could grind out more reps, if you’re not doing it the way it’s supposed to be done, you’re not getting any further benefit other than simply stroking your ego.

For most beginners and intermediates learning a new skill, technical failure is the end goal of the set, even if they can crunch through more reps. They likely haven’t built up the structural adaptations of more advanced lifters to be able to successfully lose technical aptitude to keep risks of tissue failure as minimal as possible, so for beginners, make it look right until it doesn’t, then stop.

Many sprinters and olympic lifters use technique failure as the limiting feature for their main efforts before switching to accessory work. A lifter who loses a catch at the top of a snatch may be able to get the weight up there, but pushing further into fatigue just pollutes the motor program of the movement. A sprinter who starts fast but gradually slows down or changes their run mechanics as a session drags on is also just learning to run slower, so it’s of minimal benefit to keep working on those efforts in lieu of switching to accessory work.

Mechanical failure is typically where the bodybuilding example at the start of this post train towards as a main goal. Essentially it means making the muscle contract against a load until it literally can’t complete another rep, thus failing to produce any more mechanical work.

It’s a great way to train with a couple of big qualifying conditions:

- The person has the technical aptitude to push their limits without losing their ability to do the given exercise effectively, or

- They use an exercise where technical ability isn’t a significantly high requirement

Think of a movement like an olympic clean and jerk versus a preacher curl for your biceps. The clean and jerk will be significantly more technically demanding than the bicep curl, so it would be much easier to take the curl to mechanical failure.

For this reason, a lot of isolation work can be done to mechanical failure, as well as many compound lifts where the technical requirements aren’t highly precise or where the loading isn’t significantly close to an individuals maximum.

The risk of tissue failure here is higher than with stopping at technical failure as the physiological stress on the tissues is higher. This is an approach best used with lifters who have some established adaptation to their training to allow some guard rails to fall back on and prevent that tissue damage, versus a beginner who hasn’t even started to figure out whether their gym shorts are on inside out or not.

Absolute failure takes mechanical failure up a notch or 6. A good way to think of this is if mechanical failure occurs on a lift, but then you just change the loading and continue on past that point, until the muscle literally can’t contract any further, that would be absolute failure.

This is commonly used as drop sets, giant sets, mechanical drop sets, or any method of adjusting the loading on a movement or muscle to allow the individual to continue working past mechanical failure.

Lets use leg extensions as an example. You start with the pin at level 10, bang out 15 reps and just barely get the last one out, but then immediately set the pin down to 8, and continue along your leg extension ways until failure again. Drop the pin, go to failure, drop the pin, etc etc etc until you’re dying with nothing more than the weight of your shoe laces weighing on your toasty quads.

If you want to get the most ridiculous muscle pumps ever and feel incredibly invalidated about your own strength by the time the set is over, this is the approach for you.

However, because the stress within the worked tissues is considerably high, there’s an increased risk of tissue failure or developing an inflammatory reaction with this kind of training, so it’s best left to lifters who have the training history under their belts, or as a very sporadic method of spicing things up on occasion with isolation movements or for one or two sets of a “finisher” at the end of a workout. You could also include some negatives where you just work on lowering the resistance after you can’t complete any concentric reps any more. This is a good way to extend a set of chin ups, and a great way to be unable to extend your elbows for a few days after due to the DOMS.

The balancing act of training is imparting enough stress to see positive adaptations, but not so much as to cause serious tissue damage or worsening performance. For most beginners, they have to see some time in their workouts before leaning into the higher stress options given, and see the biggest benefits from learning how to do the movements well enough to get the benefits from them they’re after, and getting into the workouts consistently enough to make them a habit.

More advanced lifters (both in terms of lifting “age” and aptitudes) can benefit from higher stresses, but that’s because they’ve adapted to those stresses enough to not die a firey death when they give them a shot. A powerlifter with a pair of anacondas for erector spinae muscles has some larger guard rails in place for protecting against possible tissue damage of a sloppy deadlift max than your aunt who works in accounting and hasn’t lifted anything heavier than your spirits for the better part of a generation, so taking her to failure is a much riskier proposition than the snake-backed dude.

With low technical requirement movements, you can go to mechanical failure pretty easily and on a semi-regular frequency with even a beginner, as long as they recover well and aren’t seeing any signs of intolerance. For more elite or even regular lifters, this may be the goal of every single set, or could be the goals of the accessory lifts after the main working sets of their program. A powerlifter may do their squats while leaving a few reps in the tank, and then absolutely annihilate their quads and hamstrings with higher volume accessory work to failure.

As training stress goes up, so too do potential gains and risks, so finding the balance is a challenge. Play with different approaches, see what works well, build up the ability to tolerate stress, and see some positive gains all over the place.