Progress Means Disruption

I remember a number of years ago when I was still fairly young in my personal training career, I worked in a commercial facility that had squash courts, and as such we had a lot of squash players working out in there. That is to say, they played squash, then drank beer in the lounge, and the odd one might touch a weight every three months or so.

One such player had a routine. He’d play, have a beer, and then proceed to do the exact same workout every single day, including 50 1/4 curls with the 50 lb dumbbells. We got to be friendly so I asked why he did his curls that way, to which he responded “I’ve been doing them like this for 30 years, son.”

This brings me to the topic of today’s post: homeostasis and allostasis.

Your body likes a state of homeostasis, where things are working on autopilot and maintaining the status quo. You feel good, you poop nice, digestion is doing what it’s supposed to, everything is happy. This is a great place to be if you want to have a routine that prevents you from seeing rapid degenerative changes related to aging. Doing the same things, eating the same things in the same amounts, and staying relatively the same can be a great place to be for many people. This is essentially where “plateaus” fit into fitness programming. Your body has adjusted to the current stressors being placed on it, and has found a happy balancing point.

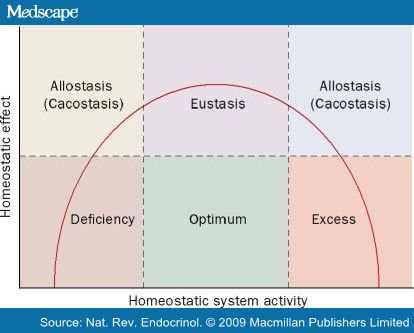

Getting to this point of balance is a bit tricky, especially if you just finished a fairly stressing time. The body can adapt to change pretty easily, depending on the amount and rate of that change application. The bodies ability to adapt and reach homeostasis is called allostasis.

Essentially (and incredibly dumbed down), if I can currently squat 300 pounds for 5 reps, and I only do that once or twice a week, I’ll be in a relative state of homeostasis. In order to see any progress to new levels of strength or hypertrophy, I’d have to force my body to do more than it currently is, which may mean squatting 300 lbs for 8 reps instead of 5, or adding 20 lbs to the bar for the same set of 5. I could also bump my frequency up from twice a week to three times a week. This new stressor would require my body to adapt, which is allostasis, in order to reach a new balance point, which is homeostasis.

Varying stress exposure on the body can be a bit of a tricky thing to have in order to encourage good adaptation. The amount and length of exposure to see benefits, called eustress, promotes eustasis, or the beneficial adaptation to the organism. If there’s too little stress on the system, you see atrophy. If there’s too much, you see degeneration or fatigue related dysfunctions, or distress.

Why this is tricky is because everyone has a different threshold for adaptation, at different times within their training calendar, and this HAS to include stressors not related to training itself, such as work, life, relationships, weather changes, nutrition, and everything else that can get in the way.

Essentially, finding the optimal amount of stress to see positive adaptation in a program is a bit of a moving target, yet still within a relatively understandable schematic. One way to see this adaptation is to simply progress what you’re currently doing, then repeat that for a few weeks until it feels somewhat easier or until you no longer want to throw your face into a garden rake or watch Keeping up With The Kardashians versus doing that workout again. Typically this adaptation should happen within about 4-6 weeks, and could happen as quickly as 1-2 depending on how much of a stimulus you’re using.

An easy way to involve this adaptation is to just add a set of a couple of exercises you would normally do within your routine. Let’s say you do 6 exercises in the gym, and each one you’re doing 3 sets. That’s 18 total sets of work within the workout, so you could bump 3 of those exercises up to 4 sets and see an increase of volume from 18 to 21 sets, which would be an overload in volume compared to what you were previously doing, or a 17% increase in volume.

Another way is to add a rep or two to each of your top sets, while using the same weights and working within the same number of sets. This increase in volume would be enough to stimulate allostasis if you haven’t adjusted your workouts in a while.

For the endurance athletes out there, you can do the same thing with run mileage, frequency, and pacing. From my experience working with runners, many are more willing to increase mileage than they are to work in lower mileages with a faster pace, and if the goal of any race is to run faster, then running longer distances at the same speed may not make you a faster runner. Running faster will make you a faster runner who can then add mileage to cover greater distances at a faster pace, but that’s just the opinion of a strength coach who prefers to cover large distances in a car with air conditioning and a cup holder.

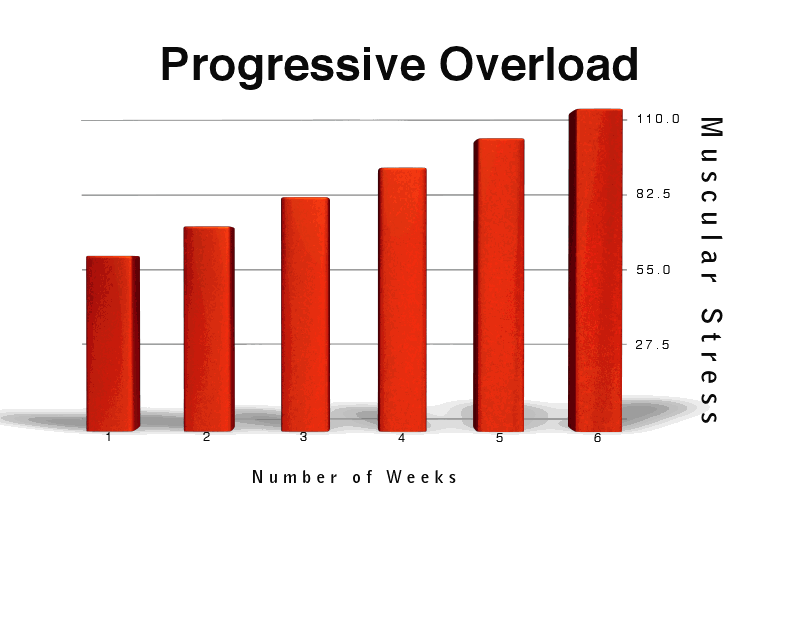

Progressive overload with time to allow allostasis is the key concept to seeing new progress in a fitness program. During this allostasis phase, consistency is more important than variety. Applying the new level of stress to the body in a relatively repeatable manner is how the body will adapt to realize the ability to use this new requirement effectively.

Varied stressors or random stressors will still allow adaptation, however it won’t be as direct or related to the specific stressor applications. Crossfit does an awesome job at applying stressors and using a variety of techniques, which can build general fitness incredibly well. One of the best adaptations they encourage is in producing a higher work capacity from the individual compared to other modalities, which is massively impactful in performing new tasks, and working within new specific stressors compared to not having that broad work capacity available.

Powerlifters and olympic lifters are excellent at adapting to very specific stressors. They may lose some of the ability to hit a golf ball or shoot a free throw, but they adapt to their specific sports incredibly well as the stressors are relatively consistent over time.

Why is this important? If you’re doing something different every week or every time you come into the gym, you’ll see a broad stressor adaptation potential, which may not be as specific to what you’re looking to improve as you may want, however it will allow for a general work capacity improvement. One key feature to this is tracking what you’re doing, as without knowing what stressors you’re putting your body through, you never know whether you’re seeing progress compared to previous weeks or just doing stuff for the sake of doing stuff.

The easiest way to determine whether you’re applying a new level of stress to your body is to repeat workouts for a couple of weeks, and add in volume or loading on successive weeks. Keep track in a log book, work at it for 4-6 weeks, or even 8 weeks, and see how you’re progressing or adapting to these new stressors.

So let’s say for example in a program you’re doing 4 days a week, you’re completing 20 sets of work within each workout, and working to roughly 8/10 effort on each set in week 1. Next week, add in 4-8 total sets through the week (1-2 a day), and keep the effort to 8/10. You might feel a bit more tired than usual at the end of the week, but good overall.

In week 3, you add another 4-8 sets of work (1-2 a day), keep the effort to 8/10, and now feel like you’re more sore than comfortable. Probably also feel like you might be coming down with a cold, or like you’re not quite sleeping enough.

Week 4, you keep the volume the same, but add in a bit more weight to make it feel like a 9/10 effort. Now life sucks entirely, as you’re working with 28-36 sets compared to only 20 in week 1, and have also bumped intensity up by about 12% based just on RPE increases, which means you’re pretty much doubling the systemic stress you’re putting yourself under compared to week 1.

Week 5, you maintain this intensity and volume, which makes you feel like you’re still hit by a truck, but now you’re getting a few more skin and digestive disturbances, you’re always hungry, and want to throat punch anyone who’s using your machines when you want to use them. It’s a happy kind of fun.

Week 6, we cut the volume in half to allow a bit of reprieve and allow you to play catch up to that previous stress while not giving you more than you could recover from. The venerated deload week.

In week 7, there’s a new program, this time starting with 4 days a week, 8/10 RPE, but now you’re working with 24 sets of work per week compared to 20, which is a 20% increase in volume from week 1, but still considerably less than in week 4 and 5, so it feels like a vacation, even though it’s progressively more than previous phases.

Another way you could make this work that is more kind and gentle, albeit slightly slower, is to go from 4 days a week at 20 sets of total volume, and just add one set per day (24 sets total weekly volume), and stick with that for a month or so. You’re still encurring more stress, but doing so in a much more gradual manner than the ramped up protocol outlined above.

This is likely what you would use for many general fitness clients or goalsets, where the person actually wants to have a life outside of the gym and relationships that don’t ecstatically implode on themselves. It’s also easier to do this within a regular time interval that most people would have to spend at the gym compared to a 2 hour marathon session that may be required for some of the super-high volume weeks outlined above.

Regardless of the method used, you’re employing more stress to push allostasis in order to achieve a new point of homeostasis, which means progress. The way you get there may be different, and rate at which you adapt to those stressors may be different, but they work on the same principles. It’s just a matter of what way works best for the individual based on their goals. I don’t see too many Mr. Olympia competitors training with the slow progressive loading, but I also don’t see Gladys from accounting wanting to hit up 40 sets on leg day and puking into a bucket between leg press rounds.

If you get to a point in your training where you feel like you’re hitting a plateau, that just means you’re used to the current stress your body is under. The best ways to bust through those plateaus are to work either with a new volume of work, a new frequency of work, or a new intensity of work. You can change the workouts to involve new exercises, which can help produce stress in different parameters, and can be very beneficial for things like general fitness, work capacity, and hypertrophy. For strength and skill development, they seem to respond best to keeping the movements consistent, and adapting the volume and loading variables versus using novel movements.

The only way to know how to adjust variables to see progress through these plateaus is to track your workouts. Look at total volume, loading, and weekly frequency, and adjust something to see an increase in work done during your training to push through a plateau. Remember though, plateaus aren’t something to avoid or stop at all costs, but rather show that you have adapted to a stress and have reached a relative state of homeostasis, which may be a really good thing. Progress is hard, both physically and mentally, so having a plateau phase can be a good “break” from hard driving in the workouts or diet, plus they give you a chance to reassess where you’re going to go with your next phase of programming and how hard you’ll have to work to get there.

To summarize:

- Track your workouts

- Change something to see adaptation

- Stay the course

- reassess when you hit a plateau

- Repeat

Did you like this post and want to know more? Check out The L2 Fitness Summit featuring myself and Dr. Mike Israetel from Renaissance Periodization, where Mike talks at length about how to produce adaptation and hypertrophy in the most effective means possible.

This 11 hour video series comes with continuing education credits, and goes in depth through assessment concepts with me, and all things programming and adaptation with Mike, plus a sweet Q & A with the two of us at the end.

One Response to Progress Means Disruption