Overhead for Older Dudes & Dudettes

Everyone can appreciate a nicely developed set of shoulders, men and women alike. One of the more effective means of developing a great set of polar ice caps under your short sleeve shirts is with pressing movements, and commonly with overhead presses. Sure, they can be developed in other ways, but we’re talking overhead over here, so let’s keep some semblance of thought-process consistency, shall we? You’re here to LEARN, not poke holes in thoughts, dammit!

That was harsh. Okay fine, let’s lighten the mood with a pic of an otter on a water slide who enjoys singing Adele.

We cool again? Great.

Anyway, back to overhead pressing. While it’s great to develop strong sexy shoulders, there’s a lot of technical stuff that goes into a successful lift that won’t make you feel like you just took a sandblaster to your rotator cuff muscles. I taught a workshop over the weekend in Toronto, and gave the analogy that the hips are strong and sturdy without that much that goes into technical alignment and set up, so they’re kind of like an old Dodge pickup truck. You just can’t kill them, and they can take a beating. The shoulder on the other hand is more like a a Lamborghini. They’re very particular and require some more finite tuning and specific set ups to get the most out of them.

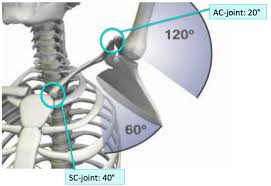

When you consider the coupled motion of the sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, scapulothoracic, and glenohumeral joint all contribute to the motion of the shoulder, and each of those joints produce motion in multiple planes of action, setting up for something as relatively specific as an overhead press, even with any amount of weight, is a pretty challenging thing for a lot of people.

A lot of people that is, except The Ultimate Warrior.

The compound motion of the sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, and scapulothoracic joint result in scapular rotation, a process by which your shoulder blade rotates on your rib cage. Ideally this rotation is relatively consistent on all sides and doesn’t result in a lot of gliding either forward or up. This rotation allows the arm to go overhead in a much more user-friendly manner that reduces the impact of the arm bone banging into the acromion process on the outer edge of the scapula, and also reduces how much stretch is put into the shoulder capsule or the requirements of the shoulder muscles to get there compared to if the shoulder blade didn’t rotate.

This rotation allows the humerus to also stay in contact with the shoulder socket (also called the glenoid fossa), and that increased bone to bone contact makes the shoulder much more stable in that overhead position compared to if the shoulder blade didn’t rotate and there was less support on the bottom of the joint. This reduced support would make the muscles of the shoulder joint have to provide that stability, which would usually not go that well.

Now one thing to consider with the older crowd of lifters is that range of motion typically decreases as the person celebrates birthdays. Joint capsules get tighter, joint spaces lose hydration and ligaments become more fibrous and rigid, making complex motions a little more challenging than they used to be. Due to the very high mobility demands of overhead through the joints mentioned above, it could be challenging to get into an overhead position with enough scapular rotation to support the position effectively. To throw another monkey wrench into the process, much of the motion of those joints is affected by whether your thoracic spine can extend or is stuck in flexion. See why I called it a Lamborghini now? Lots of moving parts.

That doesn’t mean you can’t get your swole on in other ways, or that overhead pressing is off limits. It could just mean that there’s some other things to help you get into a position to be more effective with your pressing, keep the range of motion you have, or even some other stuff to work on if overhead doesn’t treat you all that well.

So let’s start with some things that could help get you into some more scapular rotation before we push the overhead stuff.

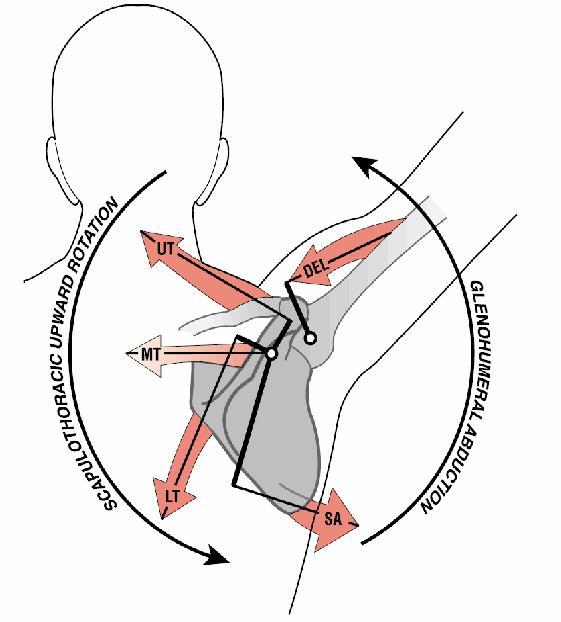

The main muscles that cause rotation of the scapula are the upper traps, lower traps, and serratus anterior. They each grab an edge of the shoulder blade and pull it in directions that, when used together, produce rotation. If they don’t work together, the shoulder blade just glides in a direction of pull and doesn’t rotate, but more lists at a lazy angle.

If rotation of the shoulder blade isn’t happening, it’s usually because one or more of these muscles isn’t doing it’s job properly. Either it’s not strong enough or the neural connection to that muscle to contract on demand is a little weak. In either case, for older dudes and dudettes, commonly the upper trap is going to be what drives most of the rotation, which tends to result in just shrugging the shoulder blade up and looking like you have no neck. It’s not a hot look for spring fashions to have no neck, so to work on getting more rotation, we would want to get some more activity from the lower traps and serratus to try to coax them all to play nicely together during overhead movements.

Here’s a video from Eric Cressey, the Sultan of Scapulas, the Guru of the Glenohumeral joint, and the Dandy of Deltoids, walking through what to look for in a lower trap raise.

The goal on this is to get the low trap muscle to pull the shoulder blade back agains the ribs, even though the arm movement is going to want to pull that blade off the ribs. A key consideration is whether the movement occurs by having the upper trap shrug and drive the shoulder blade into your neck (not what you’re after) or whether the blade stays put and the arm just moves as far as you can get it to go before the blade either starts to lift off or glides up (where the money is).

Looking at the serratus, often it’s stuck in a locked down position and can’t really contract further or relax. Getting some stimulation into it to contract through a larger range of motion than it’s used to can help spark some new action in it, and can help it contribute to upward rotation in other movements or positions. This drill from Tony Gentilcore, some dude I randomly met on the internet and whom I travel all over with to teach science about shoulder and hips, helps coach getting more shoulder protraction through focused attention on serratus action.

The goal here is to have scapular motion, not simply round your upper back. It can be a lot trickier than it feels it should be to do it right, especially if your shoulders are glued down and not able to or used to gliding around through that movement.

So we’ve got some love going for the lower traps and the serratus. Let’s put them together and see if we can promote some solid upward rotation of the shoulder blades while getting that holy trinity of turnability into play.

Since we still have to consider that straight overhead may not work all that well, we have to adjust the range of motion and direction of movement to produce rotation, but avoid driving into a range of motion that may compromise the movement altogether. We can do this by doing exercises that keep the hands in front of the body versus pushing them in line with the head or behind the head for the time being, and then expand that as the range of motion becomes easier.

Here’s Toy Bonvechio rocking a wall slide variation that uses a foam roller and requires the same serratus activation we used from Tony’s video.

A key consideration to this is make sure the back is slightly flexed, brace the abs to prevent the low back from arching into the movement, and glide up only as far as you can control the movement without some compensation somewhere else.

Another option is to do a press movement with a landmine.

You could even take it down a notch by going to a half kneeling position to increase the vertical vector of the movement.

For these, instead of trying to just jam the weight up there, try to focus on getting the shoulder blade to slide around to get your arm into that overhead position, and try to avoid letting the blade glide up towards your neck. That upward glide won’t be the cause of armageddon, but it’s best to avoid it if that’s not the goal of the exercise.

Now the thing is, depending on how adaptive your shoulders are, this could be all they have available in the means of overhead pressing, and that’s okay. The landmine press, or alternatively an incline dumbbell or barbell press, can produce some decent deltoid development, and the consistent work on scapular rotation and control can go a long way to potentially accessing that overhead range of motion. However, it’s something where if your joints literally do not allow the position, it’s not worth it to try to force it. Use what you have, slowly expand it if possible, and train hard with the best tools you have available.

3 Responses to Overhead for Older Dudes & Dudettes