Level Up

One of my guilty pleasures is a love of video games. I grew up playing all the classics, like Super Mario Brothers, Mortal Kombat, Street Fighter 2 (and 3), and a bunch of others on everything from a Nintendo to a PlayStation 2. I haven’t moved into the new generations of video games on PlayStation 3 or XBox 360, because I know I’ll get addicted to some type of game that blows peoples minds and wind up unemployed and divorced after staying up for 96 straight hours without showering or moving from the couch.

A common thread in most games is that they start off relatively easy so you can get the feel of the gameplay, then get progressively hard, crescendoing in a big finale that in theory should be the most difficult part of the game. Each time you reach a specific achievement, you gain a new ability, increase your points, or something of the nature. Essentially, you level up.

(Note: I’m also recently on Fitocracy to track my workouts and give me a mini video game experience. If you’re also on there, and I would recommend you should be, give me a follow to track my awesomeness. Click HERE to check it out)

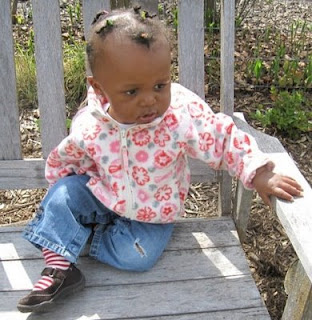

Life is kind of the same way. When you start off, you’re an amorphous blob that has minimal powers and capacity to do stuff. As time goes on, you figure out how to perform basic movements, like rolling over, crawling, pulling yourself up, going from hands and knees to half-kneeling, and eventually standing and walking into running and eventually fist pumping like champs.

The first few stages don’t do anything vertically, they’re all rolling, crawling, pushing up, and reaching. Life changes completely when the baby begins to change levels and go from crawling to kneeling and eventually to standing. These level changes each present with increasingly demanding stability requirements to make the jump from one stage to the next, and typically requires a lot of failure to learn how to succeed.

Moving from seated or crawling into a half kneeling position requires a lot of unilateral strength from the hips and thighs, as well as a coordinated sequence of contractions from the core and diaphragm, a weight shift to ensure the center of gravity is optimally placed over the base of support both anteroposteriorly and horizontally, and then the maintenance of that posture throughout the movement as the positioning of each joint is altered repeatedly through the range of motion required to complete the movement.

The requirements are the same for adults, and in many cases, the inability to create a sequenced movement pattern like this is more telling than localized weakness, stiffness, pain, or hesitation with specific movements. I can guarantee someone with back pain will have a hell of a time moving from standing to sitting, or to lying down, as well as getting back up again. I can say this because I was one of them. Changing levels was the worst. I would have rather passed a kidney stone while standing upright than try to sit down or lay down when my back was messed up.

Athletes also need to be able to change levels constantly, depending on their sport. Wrestlers are almost always moving from quadruped position to half kneeling to standing. Hockey players go from the ice to standing and back down again multiple times, especially if they’re defence and looking to block shots. It’s a fundamental skill set for anyone however, not simply athletes.

The ability to move from 2 points of contact to one, and then into a different position of 2 points of contact is paramount to our ability to move, regardless of context, environment, or amount of weight you can bench. I can almost guarantee that if someone were to come into me with chronic knee pain, hip pain, low back pain, or even shoulder pain, their ability to move from a full kneeling position to a full standing position on either leg would be somehow compromised.

Take for example, this video showing my good buddy Tony Gentilcore performing a very basic move in a bird dog. Typically the spine is supposed to stay relatively rigid and the movement should come from the hips almost exclusively. Watch the difference between his left hip extension and his right hip extension when it comes to his spine position.

Pretty messed up, right? We could beat a dead horse all day long trying to isolate the individual muscles or tissues that are weak and such, but the fact is none of the tissues are really weak. It’s a stability problem that comes from a patterning issue. I know this because on a good day Tony can deadlift over 500 pounds, and he’s eyeing up tackling 600 eventually. Strong with the force, this one is! Now, watch a recent video he shot of an exercise I had him do on his current program to help fix that naggin low back problem.

He looks pretty stable coming off his left hip, which I’m very happy about. I’d like to see how he does coming off his right hip to see if they’re symmetrical, but beggars can’t be choosers. Ideally, even if he had a little sag or hip kick or something like that going on, as long as it was symmetrical, I could just chalk it up to needing more strengthening and gaining a better command of the movement instead of it being dysfunctional.

Now let’s look at a bad example of a level change.

I mean no harm in pointing this out, and hope that this can act as a great teaching example, and I am sure she is doing her best to try to help others using the knowledge and external referencing she has available to her, which I won’t ever fault anyone on.

The basic issues with the technique on this one is a reliance on hanging the hips out in the frontal plane instead of driving straight through the movement with both legs positioned in a linear manner. I understand she’s trying to isolate the glutes, but a very fundamental fact about the body is simply:

training movements trains muscles, but training muscles doesn’t train movements

We can isolate all we want, but an integrated approach helps make the body move better and with less dysfunction. You can always cheat a muscle in isolation, but you can never effectively cheat a movement pattern and get away with it. If one area doesn’t have the requisite stability to perform a given task, it will find that stability somewhere else. In this example it comes from hanging out on lateral tension inherent in the IT band, and increased still by pronating the foot and pulling the knee inward through valgus collapse when she pushes off the ground, specifically with her right leg forward. She also gets it by flexing her hips, going through lumbar hyperextension, and having her hip flexors grip on for dear life as they do their damnedest to try to hold her spine together for her. My guess is she has chronically “tight” hip flexors and IT bands, but that’s just a guess based on her movement shown.

To do a level change is actually very simple, and something I don’t like to over-coach, as the individual has to struggle with the movement, fail, and eventually find success on their own with little coaching in order to make it authentically theirs, much like how they learned it the first time they went through it as a toddler. They simply go from kneeling into a half kneeling position without letting their hip sag out to the side or stick their butt out, and then press up into a standing position without leaning far forward to shift their weight off their back foot and without letting their hips kick out to the side. If they do a poor job, I point out the problem, tell them to fix it, and let them figure out a way to fix it. If they can’t, I adjust the movement, range of motion, or requirements to make it a doable challenge for them.

Jon Izzo demonstrates this movement very well here:

Now if you can’t perform this movement from the floor, maybe start off with a few pads or towels under the knees, so that when you go to swing your leg from the kneeling into the half kneeling position the mobility requirement on the hips is less, therefore reducing the strain on the stability system of the core and pelvis. Additionally, adding padding under the knees will help when moving from half kneeling to standing as well, as the joints are further from their terminal range of motion, and the strength available will be a lot better, which will help power through the movement.

For those who can perform these movements well, we can start creating a loading basis that can challenge the pattern further. We can use off-center loading, centered loading held in posiitons of varying length from the center of gravity, and even throw in some dynamic resistance if we want.

Here’s an example of a centered load with a long distance from the center of gravity. Watch the difference in my left and right hips and see if you can see which side I have my own back injury on.

Here’s an example of a centered load with a shorter lever length to the center of gravity, using a barbell in a back squat position.

Here’s an example of an off-center load in the form of a dumbell raised from the floor to overhead in one hand, and then moving through the pattern.

When doing any of these exercises, it’s important to remember that this should be a challenge not to the muscles, but to how your brain interprets the movement and figures out how to go from one step to the next. If it’s easy, you’re doing it wrong, plain and simple. You can see how when I was going through those movements, each step was deliberate and thought out in order to make sure I was doing the best I could to tax the movement yet make it as efficient as possible without creating compensations that would wind up negatively affecting me down the road.

The key to a level change movement is a reciprocal leg movement where one either stays in the same place or moves backwards, while the other moves forwards and through extension. A step up onto a bench or box is another example of a level change movement for those who don’t want to get their knees dirty.

The ability to perform a level change effectively helps to get better at other movements like lunges, running, and any other reciprocal leg exercise out there, which pretty much makes up everything we do in life. It’s sort of like a lynchpin, where if the person has pain anywhere and they have a crappy level change pattern, their pain will most likely decrease if their ability to perform a level change improves, especially if the issue is in their hips, knees, ankles, low back, mid back, and even their neck and shoulders due to the stabilization and mobility requirements in each segment, and their interplay with various injuries and repetitive strain irritations.

From a performance aspect, the same thing goes, but as I said earlier, You can’t cheat a movement pattern and get away with it. Bad movements lead to injuries or compensations that steal performance and lead to people complaining of the same old problems all the time. Change the training, get better results, and fist pump the night away.

18 Responses to Level Up