I’m Pretty Sure I Had COVID-19. I Have the Data To Show It Too

Currently the only way to definitively show whether you have the COVID-19 virus is with a direct test, during the time when the virus is active in your body. If you wait to essentially “heal” from the virus, the tests don’t detect an active load. Alternatively, serum antibody testing can tell if you’ve previously had it, but currently there aren’t reliable tests readily available to see if you’ve already recovered from the virus, so at this point, all I can do is speculate based on some info, connected dots, and a big ol hunch.

In late February and early March, I travelled to Athens, Greece to teach a workshop, with a stop over in Amsterdam for a day. The way back involved flying from Athens and connecting again in Amsterdam (plus the return flight involved a nice elderly women resting her head on my leg), I was in some pretty busy people places right around the time COVID was ramping up world-wide. Both places haven’t been particularly hard hit from total cases, but with travellers moving around frequently and many likely not being tested, it’s tough to say whether I came into any direct contact with anyone who had it.

I landed back in Canada March 3rd. No specific symptoms, no current recommendations within Canada that would have lead me to be tested or forced to self isolate. Those rulings would come into play about 15 days later for anyone who came back into Canada. That restriction came in to place March 18th, more than 2 full weeks after I landed. Testing didn’t become readily available for asymptomatic individuals, even those who travelled, until late March within Alberta, left primarily to emergency rooms, health care workers and long-term care facilities.

That being said, Lindsay has been using a Whoop band to track a lot of biometric data for her training and recovery, and recently we dug back in time into the specifics and found some interesting anomalies.

In the months of February through April, we found there was a period of time of about 17 days, beginning on March 6th (3 days after I landed back in Canada), where a lot of her recovery elements tanked, even though her sleep quality remained very high, and training stress was notable lower than in the previous and following months.

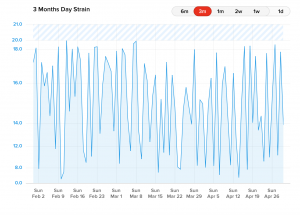

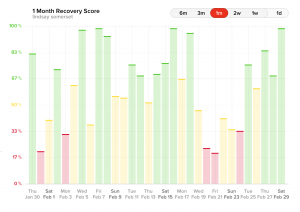

Here’s a look at her recorded recovery for a 3 month window.

This might look a bit all over the place, but if you look at the dates between March 8th and March 21st-ish, you can see that timeframe is considerably lower than the timeframes before and after.

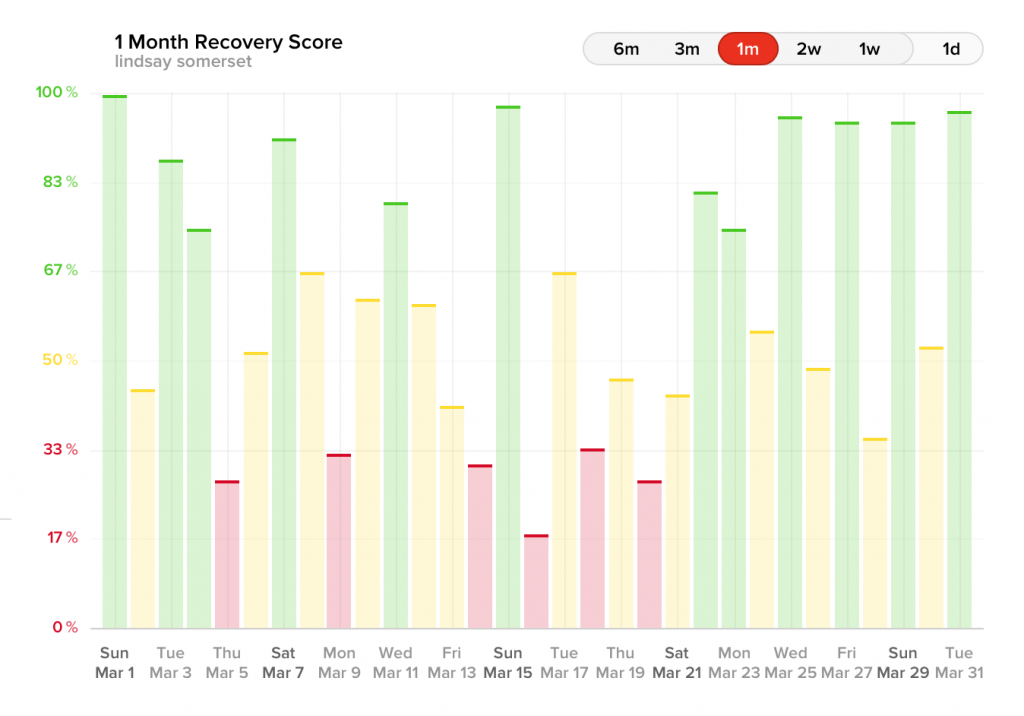

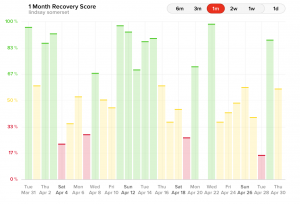

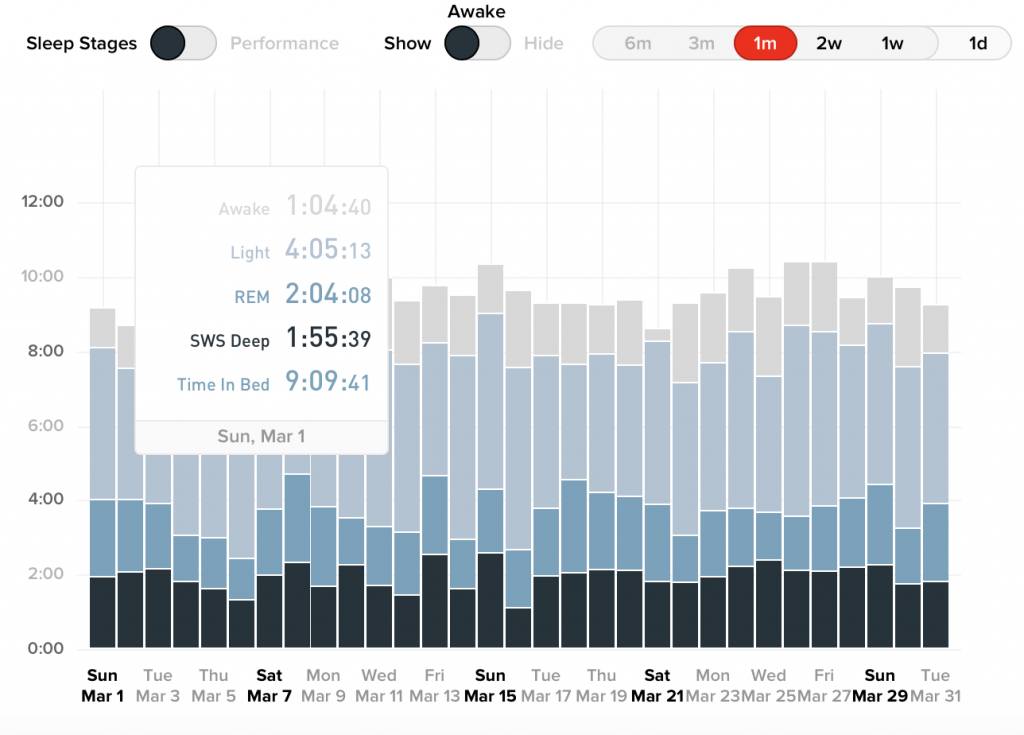

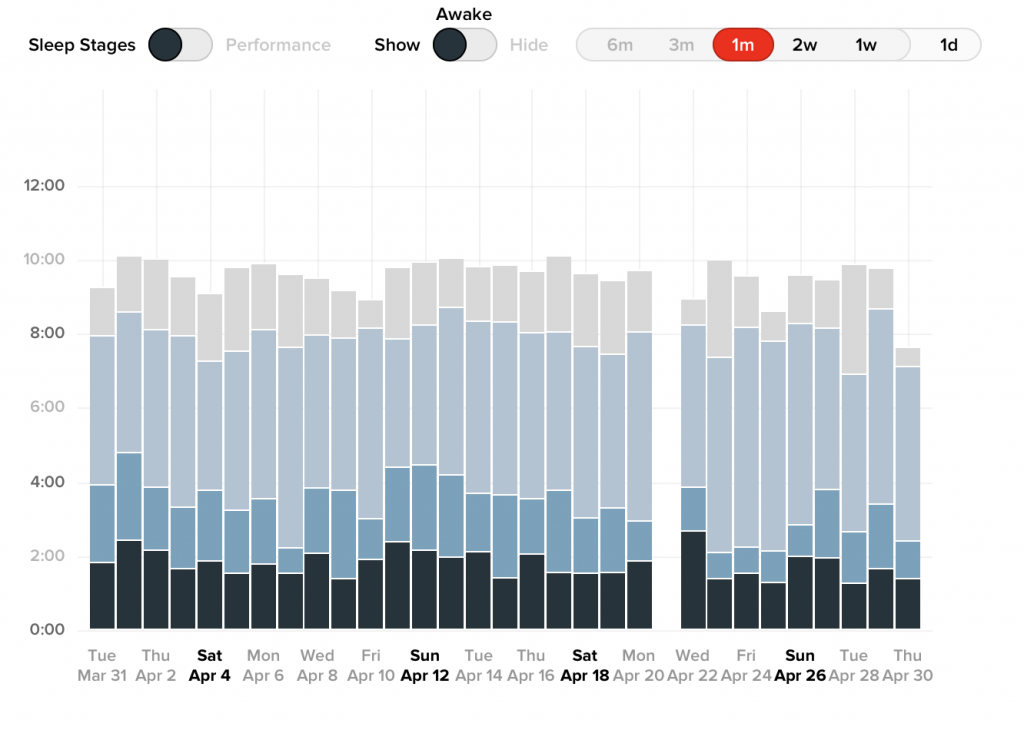

Here’s a more specific breakdown of those months.

The red days are the very low recovery days, yellow are moderate recovery and green means go. You can see February looked pretty recovered and ready to rock, but in March there was that timeframe between March 5th and March 21st that seemed significantly lower than the month before and the month after. SOME of the lower timeframes in February and April correspond with menstrual cycles, and the window in March also included a cycle, but in February and April, the recovery is low for only a day or two, not 2 full weeks.

Interestingly, her sleep score through these 3 months remained relatively the same.

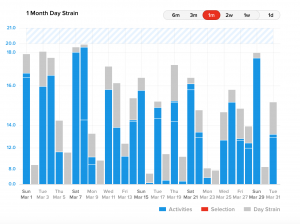

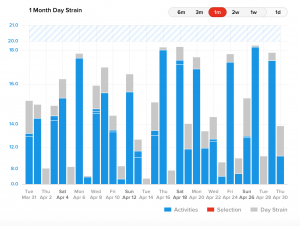

Her strain score from exercise was also somewhat lower during this phase.

Her normal strain score for February was between 16 and 18, April it was picking back up towards 16-18 consistently towards the end of the month, and between March 9-29th, she struggled to get her strain score over 16, taking more off days and lower intensity days in this timeframe.

Whoop published a blog post outlining some of the findings from individuals who tested positive from Covid-19. They found respiration rate increased by 15% (Lindsays went up on average for the affected dates by 23%), heart rate variability went down by 30% (Lindsays was 36%), and an increase in resting heart rate of 25% (Lindsays was 39% increase). This combination typically correlates to increased sympathetic stress, which means either you’re overtrained, very deconditioned and in a pathological state, or fighting some type of infection. Users who had normal flus or colds didn’t show even half of the severity of these deviations.

Lindsay checked all 3 boxes at once, had a timeframe of effect visible on the data of 17 days, and saw metric onset 3 days after I arrived home from international travel. She had significant reductions in recovery with consistent sleep and reduced exercise intensity. The reduction in recovery didn’t match up with any variation in strain that would indicate overtraining, and in fact she was under training for what she was used to, plus she was sleeping like an absolute boss, which would normally have changed for the worst if she was overtraining.

We both had very minor symptoms during this phase. I had a light cough and chest congestion that felt similar to seasonal snow mould allergies, which a lot of people were dealing with at that time of year. Lindsay had the same, coupled with more a bit more fatigue, all of which have come to be considered as symptoms of COVID-19. We both chalked it up to a combo of stress from a global pandemic and gyms shutting down, and seasonal allergies.

My belief is that I somehow contracted COVID-19 during travel, brought it home to Lindsay, infected her, and we saw the changes in her biometrics to show it for that 17 day period. We have all the ingredients that would make that happen, but we didn’t get tested in the timeframe after I returned home, so the only real way to see if we were infected is to wait for a serology antibody test to see if either of us have the antibodies of the virus, which should hopefully be available in a few weeks. I haven’t tracked my own data, so I can’t say what my results would look like, but just have to glean it from hers since we live together and all.

If you use an activity tracker like Whoop, or Oura, FitBit, maybe even Apple Watch, check back in the data and see if there’s anything that stands out. If you don’t use activity trackers, it’s still possible to be mildly symptomatic or even asymptomatic and still have contracted the virus, in spite of doing everything possible to avoid exposure.

In the meantime until we can get antibody testing, Lindsay and I are going to continue to act as if we haven’t had it, physically distancing as much as possible, continuing with enhanced hygeine, and wearing face masks when ever out in public, including now that I’m able to start in-person training in the gym again.

At this point, we also don’t know if we can be re-infected with COVID-19, but the current research is saying it’s unlikely, but we’re not going to take any chances.

Data can be cool for stuff like this.