Hypopresive Breathing Fundamentals Review

“When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body.” – Newtons third law of motion

“There are two ways of exerting one’s strength; one is pushing down, the other is pulling up.” – Booker T. Washington (not the wrestler, the 19th century civil rights leader)

A couple weeks ago, I had the opportunity to take a Hypopresive Method course offered here in Edmonton, lead by one of the master instructors who came over from Spain. This is a method of breathing, core conditioning, and pelvic restoration that has gained some popularity in working with the pelvic floor, especially for people post-partum, as well as low back disorders, diaphragmatic issues, and a host of other considerations. I was interested in taking it as a physiotherapist I work very closely with, Mary Wood and the entire team at Cura Physiotherapy, uses it extensively and some of the results they’ve seen with it have been nothing short of remarkable.

I’ll preface this review by stating the obvious, that I’m not a physiotherapist, doctor, or rehabilitation medical practitioner of any kind. That being said, i am a kinesiologist and exercise physiologist with all the appropriate designations, so I can smell BS from a mile away when it comes to faulty premises and promises. I may not know the specifics of the rehabilitation procedure for some cases such as prolapse, pelvic floor hypertonicity, incontinence, or any other consideration, but I can understand how a muscle will be facilitated, inhibited, or otherwise affected following injury and also in response to treatments. So now that that’s out of the way, let’s dig into the nitty gritty.

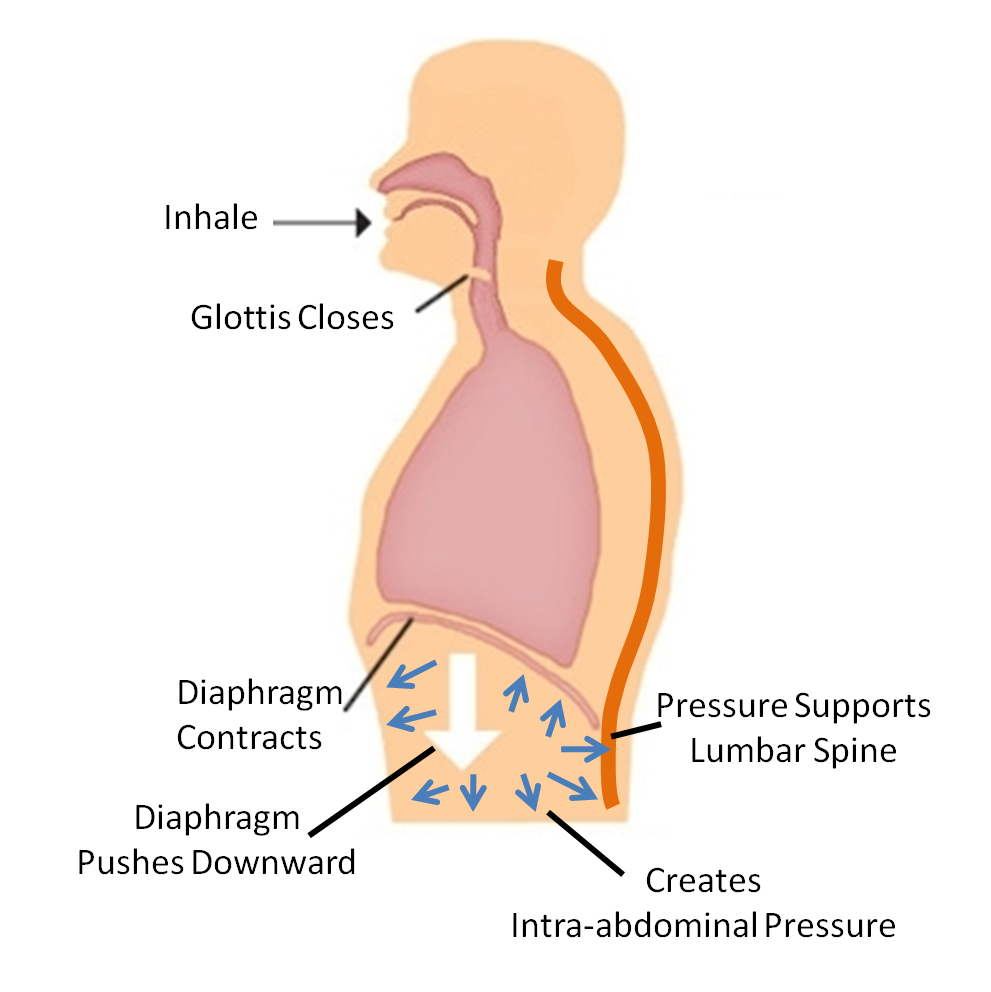

In powerlifting circles, the utilization of increased intraabdominal pressure is used to help increase spinal stabilization under heavy loading. The premise behind this is to breathe in deeply, hold the breath, and increase abdominal tension around the inflated lungs in order to increase stiffness through the core and reduce the effects of shear forces on the spine. This is ideal, except if there’s a weak point in the core complex that can’t buffer the force of this increased pressure, which eventually will lead to a herniation, either in a lumbar disc, abdominal wall (inguinal or umbilical are common), or potentially through other less desirable outlets such as the rectum.

Weightlifters and powerlifters will commonly use a belt to help manage the intra abdominal pressures and reduce the risk of pushing through the abdominal wall. You can debate for a lifetime as to whether the belt helps or hurts, but in the presence of increased pressure, you need to have the mechanisms in place to buffer them or something will give way.

The core isn’t just made of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, but also contain the pelvic floor. Just as the abs and diaphragm have to increase their stiffness to buffer pressure, the pelvic floor does too, but in many cases it loses either elasticity, rebound capacity, or both, and can be further damaged by childbirth, making it easier to have the muscle not function ideally when intra abdominal pressure increases. A common occurrence that shows pelvic floor weakness is urinary leakage or full on incontinence, especially with impact activities or hard lifting, such as running or anything Crossfit.

[embedplusvideo height=”365″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1hxhvg0″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/UKzq1upNIgU?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=UKzq1upNIgU&width=600&height=365&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep1861″ /]

This isn’t a symptom of being hardcore or excessive awesomeness, it’s a sign that you should get that checked out. For runners, if you find you have to stop every 5 minutes to go to the washroom, even after already going, you should get that looked into to make sure it’s not problematic and to help make it better.

Caufriez et al (2006) showed that the pelvic floor is also an upward curving dome structure versus the downward curving dome structure mentioned in many anatomy text books. The basic difference is that in living individuals, the dome is up, whereas in most cadavers (where anatomy can be easily gleaned), the dome inverts. This is also present when women have multiple childbirths and cause trauma to the area, and makes it harder to buffer intraabdominal pressure changes without becoming unable to absorb the stress.

So how would you train a muscular system that doesn’t respond well to increased pressure, or a hyperpressive environment, without increasing pressure through the area? Essentially everything you do to train the core involves increasing pressure. Even opening a door requires increased core stiffness to transfer force from the legs through the spine and into the arm to create movement.

Hypopresives work on involving involuntary stimulation through the pelvic floor and lower abdominals through fascial and intramuscular attachments coming from the ribs and diaphragm, specifically when the diaphragm is pulled up and the ribs are expanded. The main action is a false inhalation against a closed glotis involving rib flare and diaphragmatic elevation, essentially the opposite of a valsalva manoeuvre used in heavy lifting or when trying to crunch out a deuce.

This “pulling” movement increases tension through the diaphragmatic pillars and their attachment and interdigitation to the lumbar spine and pelvic floor attachments. This tension creates an involuntary increase in tension through the pelvic floor, and essentially draws it up, along with the transverse abdominis. With the vast majority of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall made of connective tissue that isn’t muscle (80% and 69% respecively), and only a small portion being made of type II fibers that can see significant strength and size gains, training the core in a concentric manner doesn’t really make sense, especially to people who have pathological dysfunctions.

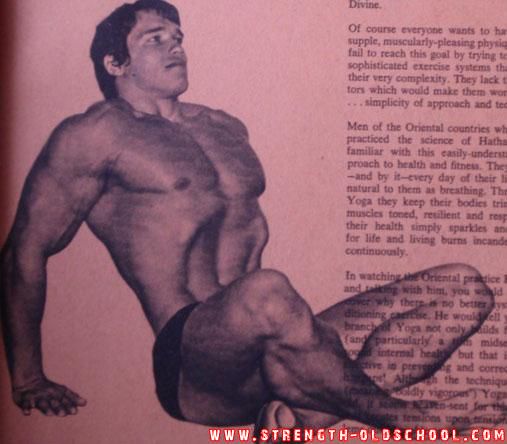

The movement was previosly used in bodybuilding circles and called a vacuum. The desired result was to slim the waist and create a better V-shape, which increased the appearance of upper body size and shape.

There’s also a similarity to a breathing mechanism used in some yoga disciplines (the name escapes me right now), but the end goal is different from yoga to hypopresives. Deep sea divers use a variation to improve their ability to handle pressure gradiations while diving in order to prevent the Bends and as a form of dryland training to improve their ability to hold their breath under tension. Much as squats can both build and tone quads depending on how they’re used, this breathing mechanism can do different things, depending on how it’s used.

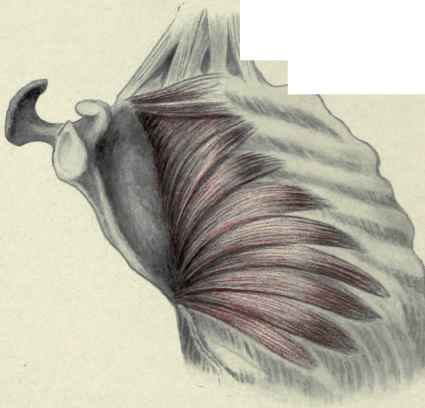

The utilization of a rib expansion is different than that observed when someone hinges through their thoracolumbar junction, as the entire rib cage opens up versus just observing a tilting with a hard arc at the low back. This opening of the ribs can provide a massive benefit to people who have kyphosis, as the ribs play an integral role in the thoracic spine. Interestingly, the serratus plays a huge role in hypopresives as they state it’s a functional antagonist of the diaphragm, but it’s primary function is to pull the scapula through protraciton on the ribs and assist in scapular rotation. However, if the scapula is fixed and in the position of decoaptation, where the shoulders are pressed out as wide as possible and held under tension, the serratus doesn’t pull the shoulder forward, but pulls the ribs out and open.

Much of the hypopresive approach can produce a sympathetic stimulation, which means it gets you pretty charged up and can raise your heart rate. This is something that’s also apparently been verified through Heart Rate Variability and also reported sleep disturbances from anyone who does it within 3 hours of their bed time.

This all sounds well and good, and I’m sure there’s a lot of people asking “where’s the research?” Interestingly, there’s a fairly large volume of it existing in Spanish, but most has yet to be translated. Much of it was also conducted by the method developer, Marciel Caufriez, and since it’s hard to double blind something like intrarectal pressure gauge measurements and intramuscular EMG analysis, there may be some research fiends out there who can poke holes in the conclusions rendered, but the data is still interesting.

Much of the research is available through Marciel’s website, but again it’s in Spanish. Some of the work has been transfered, though.

Bernardes et al (2012) showed that using Hypopresives produces similar benefit to the cross sectional area of the levator ani muscle compared with traditional physiotherapy in stage II prolapse measured with transvaginal ultrasound.

Resende et al (2012) showed that using hypopresives in conjunction with “traditional” pelvic floor exercises didn’t improve outcomes compared to “traditional” exercises alone.

Stupp et al (2011) showed that using hypopresives in addition to pelvic floor training significantly increased transverse activity, but didn’t have much benefit versus using pelvic floor exercises on their own.

What is interesting about this research is it is not readily clear as to whether the individuals who performed the testing and training had actually received training in the Hypopresive method or simply gleaned it from Youtube videos. I don’t say this disparagingly, as I thought I had an idea of what to do before the workshop as well, but found out differently upon getting specific coaching on it, and as there haven’t been any classes in America prior to the past year, I would doubt it. this could affect the outcome of the studies significantly.

Some of the research cited in the workshop are here but don’t seem to be indexed through PubMed as of yet. The results seem encouraging, yet not having ready access to a peer review process (at least in english) means the results are not easily confirmed. That said, if taken at face value, they stand pretty tall.

My Thoughts

Breathing is a massive rage in the fitness world right now. Many certification have included it in their curriculum, but most focus on diaphragmatic depression and end there. The goal is to use breathing to get people out of apical patterns and restore what is considered a more “full” breath versus a short and choppy breath. That said, what is being discussed in the fitness world is only the tip of the breathing iceberg. Before I took this workshop, I thought I had a good handle on breathing and core mechanics, and it definitely expanded what i already knew and added a lot of new information backed with quantitative data and real-time examples.

Whereas I would consider most forced breathing patterns to be more concentric in nature, this pattern seems to be more eccentric, which doesn’t mean right or wrong, just different. The concept of balance, or yin/yang kept popping up in my mind through the workshop, as did the application of these techniques for problematic core training, as well as thoracic mobilization through costal mobility, scapular dyskinesis training, and the impact it could have on deep neck flexors.

Dr. Stuart McGill has stated repeatedly that doing abdominal hollowing creates a reduction in spinal stability, which may be detrimental to low back function and injury prevention. This was based on research that looked into isolative strengthening of the multifidus and transverse known as the Australian method, and popularized in the book Therapeutic Exercise for Spinal Segmental Stabilization in Low Back Pain. This is a completely different technique, with different applications and end goals. It would be interesting to see if similar conclusions could be reached through McGills lab on these protocols and if so, how would they differ from the Australian method.

While the conclusivity of the application of these techniques is still to be determined, I’m willing to apply them to myself as well as my clients, where appropriate, to see the results it can generate. All tools have a purpose, with a specific application to produce a specific outcome. This is another tool I can use, and should at the very least consider viable until proven otherwise or until I see it not producing benefits for my clients. Int he ones who I have used it with, there has been a difference in how they feel, how they stand, and in some instances how lost function has come back and in relatively quick manner.

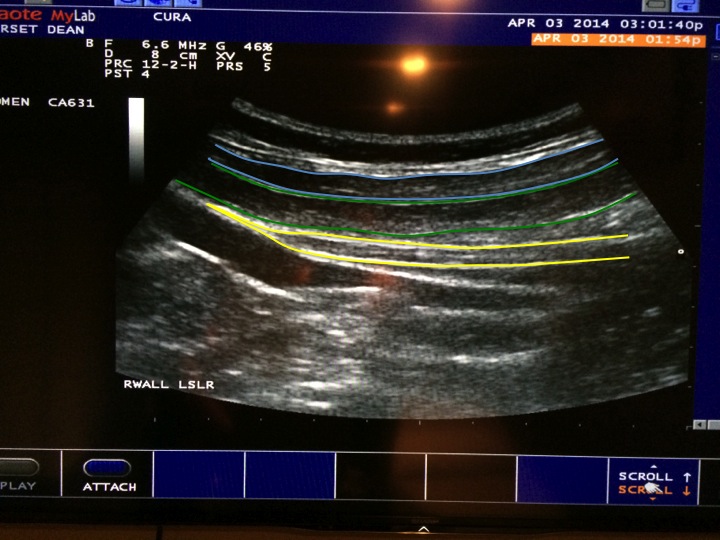

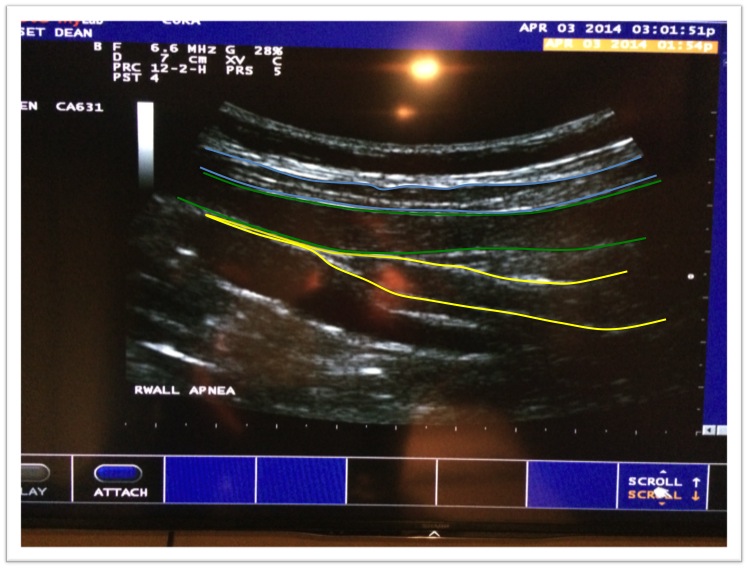

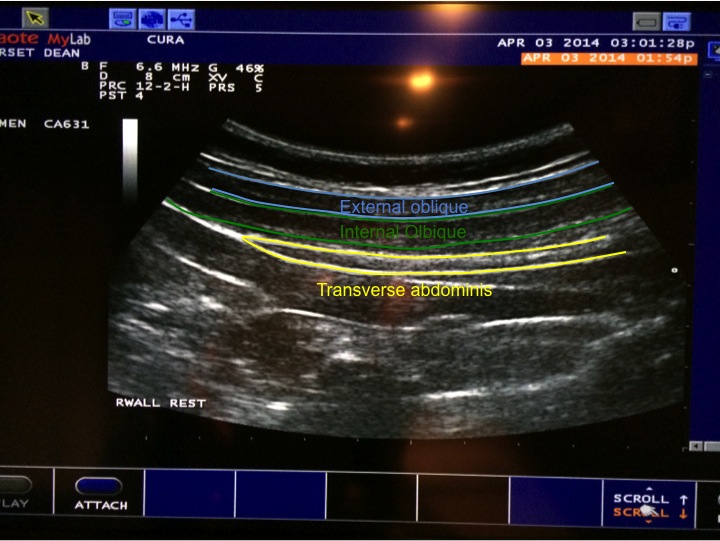

Last week I went to Cura physiotherapy to test out their RUSI ultrasound on different core activation patterns while performing regular bracing, externally cued bracing, hypopresive breathing, and a few other concepts, and found that it did indeed increase cross sectional area of the transverse, along with provide an elevation of the pelvic floor compared to other methods.

Active straight leg raise. Internal oblique was working hard, transverse wasn’t. Ideally they should work together.

During a hypopresive apnea. The transverse thickness was considerably more, and the internal oblique was working together with it.

My curiosity lies in potentially using this to augment intra abdominal pressure increases with heavier weight lifting, sort of a pressure release valve so to speak, to help train the core in both a pushing out manner and pulling in manner, to help improve lumbar strength, stabilization, and long term injury reduction. I may hit 500 pounds on my deadlift if this works well, so time will tell.

7 Responses to Hypopresive Breathing Fundamentals Review