How To Train Around Hip Pain for Hockey: Your Off-Season Survival Guide

With hockey players entering into off-season training, I wanted to showcase some ways to get jacked and swole while also avoiding some common issues hockey players wind up facing on a regular basis.

Today I have a guest post by NHL performance coach Kevin Neeld and co-author Travis Pollen. Kevin and Travis just released Speed Training for Hockey, a brand new book and series of age-specific off-season training programs for hockey players.

Speed Training for Hockey is ON SALE NOW through midnight on Sunday, May 26th for 38% off. For more information and to grab your copy, CLICK HERE.

*****

Hip pain is exceedingly common in hockey players. Due to the repetitive nature of the skating motion, every player – even the “healthy” ones – flirts with some sort of overuse or under-recovery of their hip musculature over the course of a season.

This pain can correspond to a range of diagnoses, from adductor-related groin pain to osteitis pubis, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, and sports hernias (i.e. lower abdominal tears). The most common diagnosis of all, though, is femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

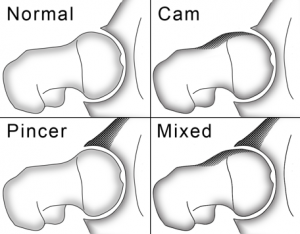

FAI is a structural abnormality of the hip characterized by a bony overgrowth of either the head/neck of the thigh bone (“cam impingement”), hip socket (“pincer impingement”), or both (“mixed”). In fact, one study reported that by the time they reach their late teens, a whopping 9 out of every 10 hockey players have FAI (Philippon et al., 2013).

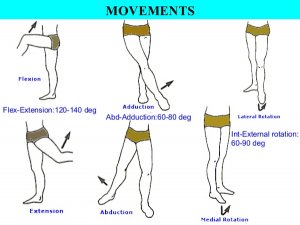

While not every athlete with FAI will be symptomatic, FAI tends to affect a player’s ability to flex their hip (i.e. bring their knee closer to the chest), causing end range of motion to be painful. While normal hip flexion range of motion is about 120°, it’s not uncommon for a hockey player to be limited to 90°. FAI can also limit range of motion in other directions, too (adduction in the frontal plane and internal rotation in the transverse plane).

These range of motion restrictions affect players both on and off the ice. Players with FAI struggle to assume an optimally deep skating position. They also tend to push up instead of out when they start to skate from a stop. In training, these athletes find it difficult to squat to parallel (let alone below).

There are a number of factors that influence the recommended course of action for dealing with FAI. These factors include the degree of bony overgrowth, severity and longevity of symptoms, and history of attempted treatment approaches. Depending on the severity of FAI, surgery may even be warranted.

No doubt, FAI is a physical limitation that we can’t directly change through training. After all, you can’t “un-grow” bone. But in many cases, a few simple workarounds can keep an athlete on the ice and making performance gains.

Training Around Femoroacetabular Impingement

Step 1. Be Aware & Minimize Damage

When it comes to training around FAI, the first step is awareness. Many coaches assume their athletes have full hip range of motion. They think that if an athlete is skating high or not squatting deep, then the athlete is either lazy or not strong enough. While those explanations certainly aren’t out of the question, given the data they’re not great assumptions – and the consequences can be costly. Forcing players with FAI to skate or squat lower can actually cause additional damage to their hip labrum.

One quick and dirty way to determine the amount of hip flexion range of motion an athlete has is the quadruped rock test. Have the athlete get into a quadruped or all-fours position with their hips over their knees, their shoulders over their wrists, and their backs flat. Instruct them to slowly rock their hips back towards their heels. Stop them as soon as their hips start to tuck under and their lower back rounds.

With this test, we want to note two things: (1) the athlete’s hip angle in the rock-back position and (2) any pain provocation. The hip angle here represents the individual’s available hip flexion range of motion. To minimize damage, athletes should avoid exceeding this hip angle whenever possible both on and off the ice.

We also want to ask the athlete if they have pain during the test. Pinching in the front of the hip is a tell-tale sign of FAI and/or labral issues. Obviously, it’s not within a coach or trainer’s scope of practice to diagnose anything, but knowing an athlete’s hip flexion end-range is important information to have from an exercise selection standpoint.

For this test, it’s especially important that the athlete sets up in a “neutral” spine position to start. Many players will gravitate toward a more extended starting position and will therefore start to “tuck” early as they rock back, which can lead to a false positive on the test.

One way to ballpark neutral is to find the midway point between the cow and cat yoga positions. Of course, if the athlete has more range of motion into extension (cow), the middle may not be a perfect indicator of neutral, but it puts you in the ballpark.

Step 2. Work Around Common Issues in Training

Once we know that an athlete has a limitation, we can start to develop workarounds in training. Again, we want to remove provocative positions and opt for exercise variations that honor the athlete’s non-compensatory, pain-free range of motion.

This process often means making the following substitutions for bilateral lower body exercises:

- High box squats instead of free-standing squats

- Rack pulls and block pulls instead of deadlifts off the floor

- Olympic lift variations from a hang position instead of off the floor

- Low box jumps instead of high box jumps (which are pretty pointless regardless of the condition of your hips)

For each of these exercises, we’re looking for the hip range of motion through which the athlete can maintain a flat back. Just like in the quadruped rock, once an athlete exhausts their hip flexion range of motion, their hips and lower back will compensate by tucking under/rounding. Range of motion on these exercises (i.e. box height for squats and box jumps, pin/block height for deadlifts) should be adjusted to the individual.

In addition to bilateral movements, we can also emphasize unilateral (single-leg) exercises. Unilateral exercises are often better tolerated than bilateral ones, as they provide more “wiggle room” for the hip and spine in the frontal plane. A few go-to unilateral exercises for hockey players are step-ups, rear foot elevated split squats, and singe-leg “reverse deadlifts.”

To avoid deep hip flexion, we can use a low box for step-ups (12-18 inches).

For rear foot elevated split squats, we can aim for an upright torso position (as opposed to a forward lean), and we can stack a pad or two under the knee of the back leg.

For the single-leg reverse deadlift, instead of reaching straight behind you with the non-working foot (as you would in a traditional single-leg stiff-legged deadlift), reach for and tap the floor behind you with your back toes. This modification requires less hip flexion than its stiff-legged counterpart.

For athletes with more progressive or persistent limitations, sled pushing and dragging are great options for both speed and conditioning work. With the sled, the athlete is free to stand as tall as necessary to stay clear of their hip restrictions.

In terms of speed work, another consideration is the athlete’s starting position. Athletes with FAI should avoid 3-point, 4-point, and half-kneeling starts. Instead, they should prioritize 2-point (standing) starts. They can also modify the half-kneeling position by placing pads under their back knee (as with the rear foot elevated split squat). Once the athlete is in motion, we won’t emphasize knee drive as much as we normally would with asymptomatic athletes.

Bottom Line on Training Around Hip Pain

To reiterate, the first step in training around hip pain is to identify each individual’s unique, pain-free hip range of motion. In reality, given human anatomical variation, this is what we should be doing with every joint on every athlete. Hopefully, the days of coaching everyone into some arbitrary movement norm are a thing of the past.

From there, it’s about avoiding ranges of motion the athlete doesn’t have access to. We do this by selecting appropriate bilateral and unilateral strength and speed training variations. Finally – and above all else – we use pain as a guide to avoid doing anything that hurts.

Over time and with practice, these modifications will become automatic. Athletes will learn to move within the confines of their anatomical joint limitations without conscious thought. It’s important to note, however, that while we can do our best to avoid provocative positions in training, we can’t always do so in sport. Even though not all of the above modifications will transfer to the ice, we can at least minimize the damage we do in training.

Want to learn more about training for hockey around hip pain?

Speed Training for Hockey is both a brand-new book and series of age-specific off-season training programs for hockey players. It’s specifically designed to help hockey players reach their genetic speed potential – no matter their age, current skill level, or injury history.

Speed Training for Hockey includes

- Comprehensive training programs for U-14, U-18, and 18 & over players totaling 36 weeks of programming, all designed with the specific purpose of increasing speed

- An extensive exercise video database demonstrating proper technique for every exercise and drill included in the program

- A systematic 20-item performance testing battery, which enables you to identify individual strengths and weaknesses and track training progress over time

- A user-friendly text that describes all of the factors that influence speed development, so you can understand exactly why the methods work

Every aspect of the training programs — from the dynamic warm-up, to the speed and power drills, strength training, conditioning, and cool-down — is tailored not only to maximize on-ice performance, but also maximize durability and minimize risk of injury. The training programs even specify systematic weekly progressions to improve speed every single session.

Speed Training for Hockey is ON SALE NOW through midnight on Sunday, May 26th for 38% off.

For more information and to grab your copy, click the following link: Speed Training for Hockey.

About the Authors

Kevin Neeld is the Head Performance Coach for the Boston Bruins, where he oversees all aspects of designing and implementing the team’s performance training program, as well as monitoring the players’ performance, workload, and recovery. Prior to Boston, Kevin spent two years as an Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach for the San Jose Sharks, and before that he was the director of a private sports performance facility in New Jersey for seven years, working with pro, college, junior, and elite level youth hockey players. He has also served as a strength and conditioning coach with the U.S. Women’s National Ice Hockey Team for the last five years.

Kevin is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist and Licensed Massage Therapist holding a master’s degree in Kinesiology & Exercise Neuroscience from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and a bachelor’s degree in Health Behavior Science & Fitness Management with a minor in Strength and Conditioning from the University of Delaware. He’s currently a doctoral candidate in Rocky Mountain University’s Human and Sport Performance program. Kevin lives in Newton, MA, with his wife Emily and son Cameron.

Travis Pollen is a PhD candidate in Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at Drexel University. His research explores the relationships between core stability, movement screening, load monitoring, and injury risk assessment in athletes. In addition to his scholarly activities, he is an NPTI-certified personal trainer and fitness writer with a special interest in the intersection between rehabilitation and