How Do I Train Myself?

Todays post was inspired from seeing a similar post written by Ben Bruno on T-Nation here. Ben’s an incredibly awesome guy, and if you don’t know about him, you can check out his website HERE.

Trainers and strength coaches are always pushing the Kool Aid on our clients and athletes about how to work out, eat right, live a more productive and anabolic life, but the amount of time we use to craft our own bodies tends to have an inverse relationship with the number of people we help out. In all seriousness, on a day when I’ve trained 10-15 clients in one-on-one or small group sessions, had all of 2-3 small hour or even half-hour breaks to eat, return phone messages, answer emails, and prepare for the next block of clients, getting my own pump on is not an immediate thought.

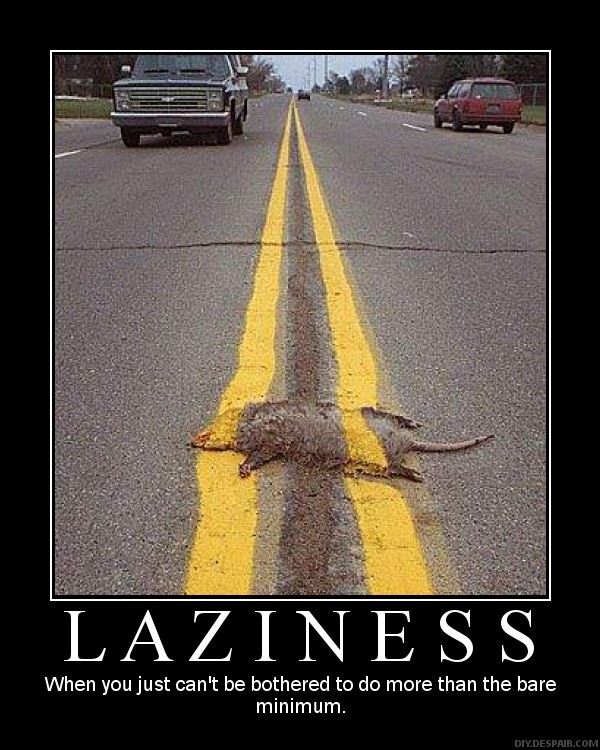

This is not an excuse, but an obstacle to overcome. I could be lazy and just not workout, but as the old saying goes, laziness doesn’t get the roadkilled possum off the road before the line painters come.

For those who don’t know, I’ll give you a little background. I’ve had low back pain issues resulting from a lax SI joint for the better part of the last 10-13 years. This has resulted in intermittent bouts of not being able to put on socks in the morning or even walk with much effect, intermixed with periods of feeling awesome and lifting ungodly amounts of weight whenever I can. As a result of this, I am perpetually gun-shy when it comes to moving to failure, and an increased focus on mobility, soft tissue work, and core stability work.

As a result of this and trying to cram 24 hours into a 13 hour day at work, most of my workouts are between 30-45 minutes long, consisting of primarily compound movements that focus on high force production, like deadlifts, squats, bench press, cleans, and chinups to name a few, as well as the “boring” staples like dead bugs, bird dogs, planks, pallof press variations, and other “anti-” ab exercises that focus on anti-extension, anti-flexion and anti-rotation work. I’ve found this to be the most effective use of my time, in keeping with my goal set of increasing my overall strength without breaking in half or becoming crippled, and also keeps me focused without letting me get too distracted by thinking of all the other things I need to get done in the day. I try to get in 3-4 days of lifting each week.

My focus is less on moving the weight and more on moving the weight with as close to perfect mechanics as possible. When Iw as making a push for hitting a 405 pound deadlift last year, I began to video each of my deadlifting workouts and re-playing them on my rest breaks so I could critique my own lift and make adjustments as needed. This went on for 4 months, twice a week.

I don’t train to failure anymore. This came from the realization that I like to be able to walk and put on my coat at the end of the day. Since I’m in my 30’s and have a history of small injuries here and there, I want to make sure I can move well on a consistent basis and not feel my age, or the age of an 80 year old, so training to failure and minimizing delayed onset muscle soreness is somewhat more important.

Plus, I’m 228 pounds. I don’t need to grow any more. I’m more concerned about what the muscle can do, not simply how big it is. By not training to failure, I can assure my nervous system is still firing properly, which will help when I need to have core stability after the workout to prevent throwing my back out again, and also to make sure I can get outside and run with my Boot Camp group on Mondays and Wednesdays.

On top of the weights, I try to bike to work each day that the weather permits. This gives me 15-20 minutes in the morning and evening to work on conditioning, which helps address features that weight training alone can’t get to, such as anaerobic threshold, aerobic power, and work capacity. Plus, it saves gas, and since we only get 6 months of non-snow weather, it just plain feels good to get outside while there’s some above-freezing temperatures.

On top of that, working as a trainer keeps me on my feet pretty much all day, demonstrating exercises, spotting, correcting, manipulating, and getting as hands-on as possible without crossing the border into Creepy McCreepy-pants territory helps me stay active in a bunch of different directions and hauling different loads. I figure in an average day I walk about 3-4 miles around the club, move 2,000-3,000 pounds of weight on and off machines as well as on and off barbells, plus dumbbells and kettlebells.

One aspect of training I’ve always wondered about was my recovery. I know I don’t work out 15 times a week, but recovery is about the total stress on the individual, not merely the exercise stress. I’ve worked with cancer patients who need much more recovery between training sessions than the average person and who can’t tolerate higher intensity work, whereas others are able to go until I think they should theoretically be hugging their knees in the corner, vomiting on themselves and quietly sobbing.

For me, I’ve felt a little more tired lately than at the beginning of the year, which I could attribute to a de-load from a very busy first 6 months of the year, to an increase in training frequency and intensity, or to any number of things. Much like I hate guessing when it comes to training, I have always hated guessing when it comes to recovery, which is one reason why the concepts of Heart Rate Variability somewhat intrigue me. To be honest, I never even touched on HRV while in university, but then again it was so long ago (all of 2004!!!).

Kevin Neeld did a very good job explaining what HRV is and why it is incredibly important to fitness, performance, and even disease management. Check it out HERE.

As a result of my own geek-tastic interest and desire to learn new things, I bought the monitor and iPhone adapter from MyIthlete.com to see what I could learn from it, and also see if I could make my own training and recovery better with some of their suggestions. I should note I don’t get a penny from any sales of this product, and am simply saying I’m trying it out to see what it’s like.

I’m a big believer in keeping stress at a reasonable level, where it can be used productively instead of destructively. Too much is never good, and too little is also a bad thing, so finding that happy zone may help me dial in a 500 pound deadlift later this year.

SO what about you? What kinds of things do you work on in your training? Let me know in the comments section and we can get a good discussion going on what everyone is doing and maybe inspire some people to do more awesome things.

21 Responses to How Do I Train Myself?