Hip Internal Rotation – What You Can and Can’t Do to Improve It

Today’s post comes from Alex Kraszewski, a physical therapist who actually lifts a metric ton of weight (because, English), while also knowing a thing or two about structural anatomy, mobility, and getting jacked as all hell. Enjoy.

*****

Hip internal rotation is kind of a big deal. You need it to walk, squat, twist, and perform like a savage. The range of hip IR someone has comes in all shapes and sizes – your grandpa who’s having his hip replaced tomorrow probably has less than 5 degrees of IR, whilst the young gymnast down the road with joint hypermobility could have up to 90 degrees of hip IR. It might even be different on one hip to the other.

On average, if you’ve got between 30 and 45°, you’re probably in a good place. If you’re not sure how to assess it, check out Eric Cressey and his great Movember ‘tache here for a quick and easy way to measure this here;

You can also use the supine position if you prefer – both of these have shown to be reliable in the research, as long as you ensure the pelvis doesn’t hike up as you get towards their end-range of motion;

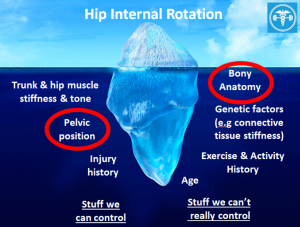

There’s a boat load of things that can influence your hip mobility and range of IR, some of which we have control over and some we don’t. We’ll focus on two of these for this post.

For those that we can control, this is where the techniques and interventions come in. Whether it’s manual therapy, band mobility drills, breathing & repositioning exercises or whatever else is in your toolbox, these can improve hip IR, but there may a ceiling to how well these work, based on the stuff we can’t control. The main one to be aware of here that can get missed is the bony anatomy and architecture of the hip. Although we may not be able to control or change the anatomy of our clients, having a good understanding of it can help make the right choices for training. Force-feeding exercises onto anatomy that is not able to appropriately deal with these stresses at best limits progress and gains, and at worse contributes to pain or injury. In the hip – this commonly crops up as hip, groin and buttock pain as a result of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

The stuff you can’t control – Bony Anatomy

Structure influences function, so the shape, size and orientation of your femur (ball) and acetabulum (socket) will dictate, amongst other movements and factors, the internal rotation of your hip. Dean has talked about this extensively in the past here,hereand here, but there’s been some other research published in the meantime that’s worth looking at to add to this picture.

Ball & Socket Orientation – Femoral & Acetabular Version

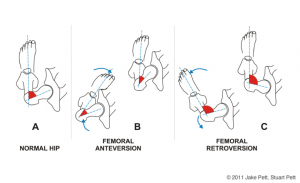

Probably the biggest determinant of rotation is the ‘version’ of the femur & acetabulum – the angle of the neck of the femur relative to its shaft. With the foot facing forwards, a retroverted femur projects posteriorly (backwards) and often presents itself as an apparent loss of hip IR and increase in ER, whilst an anteverted femur will project forwards and shows the opposite mobility – more IR and less ER.

http://www.iadms.org/blogpost/1177934/General?tag=anatomy

The hip socket (acetabulum) is the same deal – a retroverted acetabulum is more outward facing and again will reduce internal rotation, whilst the anteverted acetabulum is more forward facing, allowing for more internal rotation.

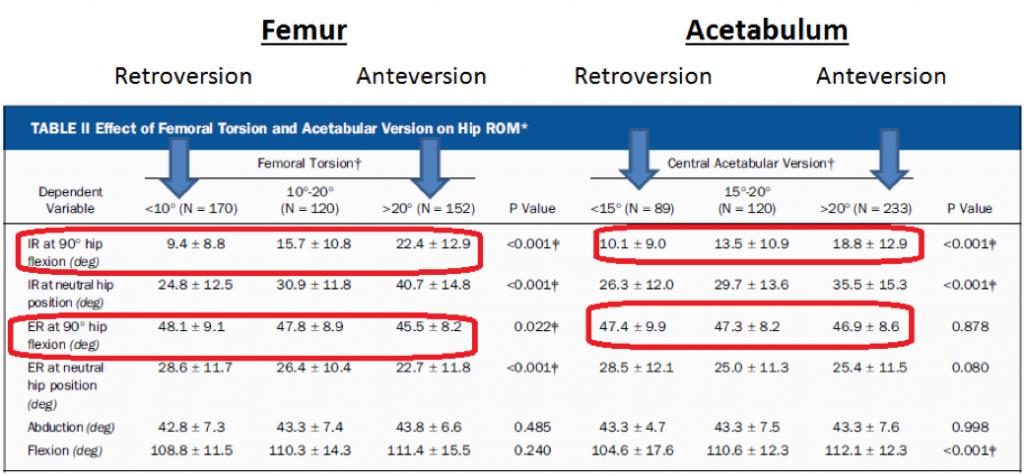

There was a great study a couple of years ago from Chadayammuri et al (2016), who mapped out the shape and orientation of their patients’ hips using CT scans and hip arthroscopy when undergoing hip surgery. In their first data set, they validated the concept that retroversion (of either the acetabulum or femur) meant more ER and less IR, whilst anteversion meant less ER and more IR.

Interestingly though, it wasn’t a fair trade-off. Femoral retroversion meant less 13° less IR compared to anteversion, but only 3° more ER, whilst acetabular retroversion meant over 8° less IR, with only 0.5° more ER. If you’re dealing with more retroversion in either the femur or acetabulum, you’d be forgiven for feeling like you got a bad deal.

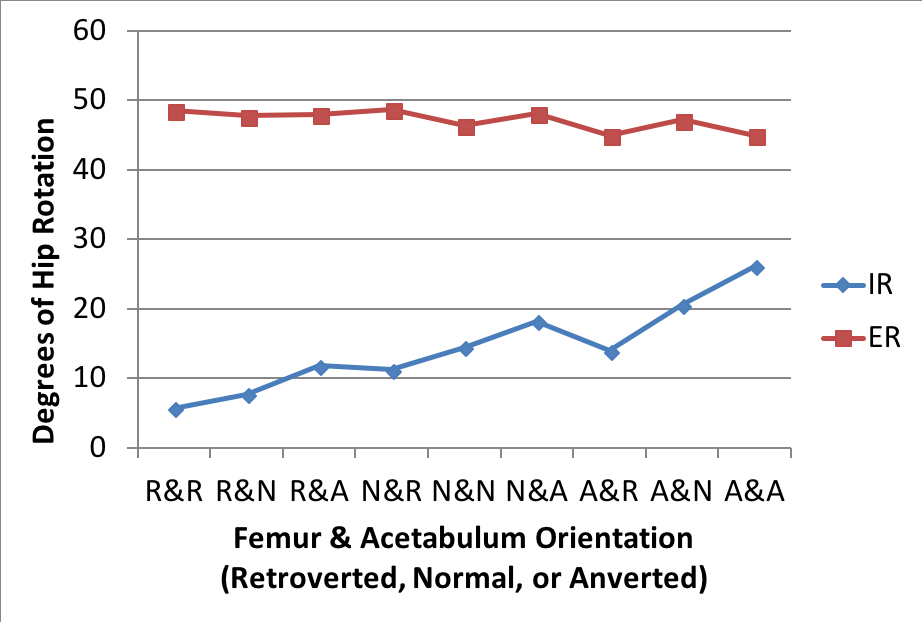

In the second part of their analysis, they compared the combinations of femoral and acetabular orientation (retroverted, normal, anteverted) on hip range of motion, and found some pretty consistent results. As the femur and acetabulum move from retroversion into anteversion, IR generally increases (5.7° to 26.1°), and whilst we’d expect to see ER decrease, it only drops off by 3.6° (48.6 to 45°).

Although there are a couple of decreases along the way – these seem to relate to a component of retroversion when IR drops, or anteversion when ER drops.

The disclaimer we have to put on this research is that it’s looking at a population who’re undergoing hip arthroscopy, which may be why we are only seeing a maximum of 26° IR, compared to the ‘norm’ of around 40-45° you might see in a healthy population.

So what am I supposed to do with this?

If you’re seeing a loss of IR, but a ‘normal’ level of ER (rather than a significant increase) then it’s likely that you’re working with someone with a retroverted hip. This isn’t a problem, it just means that you may have to taper some of your exercise selection, but also be aware that interventions that can increase hip IR may not make significant changes if the underlying bony anatomy is not forthcoming with allowing more IR.

Pelvic Tilt – Something we can control

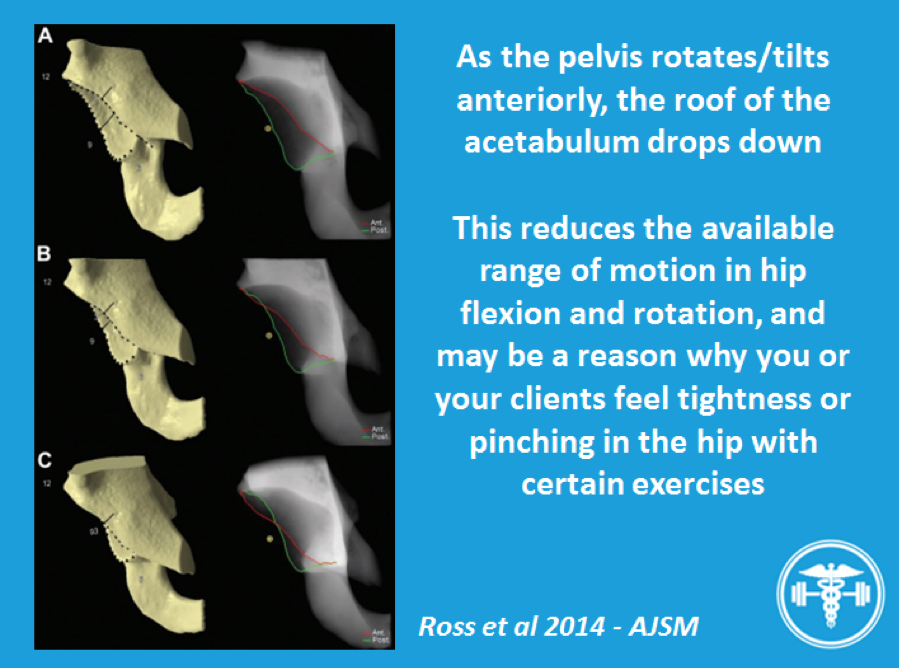

Although we can’t change bony anatomy, we can influence the position of it. The amount of pelvic tilt that someone spends their time in, whether it’s during their daily activities or during sport & exercise, will affect how much IR is available in the hip. In a more anteriorly tilted/rotated position, the roof of the acetabulum will cover more of the femur, and alongside reducing hip flexion, IR will also be affected. In one study by Ross et al (2014), this varied by 11° between habitual posture (32° IR), increasing anterior tilt (26° IR) and increasing posterior tilt (37°).

If you want to compound a reduced range of IR, then add some anterior pelvic tilt to the mix just for good measure. Interestingly, this is what some research demonstrates too – that those with FAI, almost paradoxically, will either use less posterior pelvic tilt during hip-flexion exercises (straight leg raise, squats) or make an anterior tilt their preferred position (Pierannunzii et al 2017). However the good part is, this is something that we can address for our patients & clients to help get the most out of their anatomy, if it’s not favouring them.

Disclaimer – there are times where encouraging more posterior pelvic tilt are not ideal, and that’s when you’re moving towards end-range and creating lumbar flexion whilst under heavy load. Repeatedly buttwinking during your squats, or flexing your low back whilst deadlifting may well be creating injury mechanisms for your clients.

However, moving from an extended position towards neutral/not end-range posterior tilt is much less likely to create a problem. Equally, if you’re working something without any significant spinal load (think dead bugs, planks, stability ball hamstring curls, back extensions) then you can probably get away with a little extra posterior tilt, particularly if you or your client is living in extension for a lot of the time outside the gym.

For some people, particularly those who have had a longer history of hip pain or FAI, the awareness of getting into a posterior tilt might be challenging enough in itself. This can be an important opportunity to use some lower intensity exercises to take someone from extension towards mid-range, before further using these movement habits under external load.

The 90-90 hip lift is a good place to start, and performed correctly, will help encourage posterior tilt of the pelvis without much else;

You can also add some hip shifting in this position too to encourage some more movement of the pelvis

These are useful within a warm-up or filler exercises to help encourage this posteriorly tilted position as and when required. They’re supposed to be low intensity activities – so don’t worry about crushing the foam roller or crushing your abs with an abdominal brace.

If you’re interested in more of these, the Myokinematic Restorationcourse through PRI is a good starting point to get a more in-depth understanding of how pelvic position can influence movement (in 3 planes, not just the sagittal plane as described here).

Making Sensible Decisions

A good assessment will look at both active and passive movements and capabilities. It’s important to see how someone chooses to move during exercise, but it’s also important to make sure the joints can get into the right positions to absorb and adapt to stress (thanks to Charlie Weingroff for that one). Sometimes they are hard anatomical reasons why this isn’t possible, and there is a high risk-reward ratio for choosing exercises that anatomy doesn’t deal well with.

Having said that – there is almost always an opportunity to improve what we’ve got. You may not go from 10° of IR to 45°, but if you can create more to make more exercise accessible, you’re onto a winner. The research that’s coming out around hip anatomy, if you’re a hip nerd like me, is exciting because it’s giving us more and more understanding of the factors affecting hip range of motion. If you’re a trainer, then being aware that there are things that may beyond the influence of techniques and non-surgical interventions will keep your clients out of pain and out of corrective-exercise-rehab-purgatory.

References

Chadayammuri V, Garabekyan T, Bedi A, Garrido-Pascual C, Rhodes J, O’Hara J, et al. Passive Hip Range of Motion Predicts Femoral Torsion and Acetabular Version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016 January; 98(2):127-134.

Ross JR, Nepple JJ, Philippon MJ, Kelly BT, Larson CM, Bedi A. Effect of Changes in Pelvic Tilt on Range of Motion to Impingement and Radiographic Parameters of Acetabular Morphologic Characteristics. Am J Sports Med. 2014 October; 42(10):2402-2409.

Pierannunzii L. Pelvic posture and kinematics in femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2017 September; 18(3):187-196.

About the Author

Alex Kraszewski is a Physiotherapist working in Chelmsford, Essex, in the UK. Aside from loving Deadlifts, Alex spends his time assessing, treating and rehabilitating clients in the public & private sectors with a focus on resistance training. Alex regularly publishes content on his facebook page – Rehab to Robust.

One Response to Hip Internal Rotation – What You Can and Can’t Do to Improve It