DNS Weightlifting Review

A few weeks ago I was fortunate to attend a DNS Weightlifting workshop put on through Somatic Senses in Vancouver, with the instructor being Dr. Richard Ulm. This was my first exposure to any of the DNS systems, and it was a nice ease-in for a non-therapeutic population.

Much of how we move is determined by reflexive actions that become trained and learned patterns as we develop. In some instances, those patterns become somewhat distorted, either through pathology or through specific training to produce a desired outcome. It’s pretty rare that someone would have to squat 400 lbs in their daily life if not spending copious hours in the gym, so the breathing patterns that work really well to produce the intra-abdominal pressure to move that weight have a cost of potentially altering breathing patterns that would otherwise increase activity through the other respiratory muscles, and especially so at a lower intensity, like sitting in a car or standing in line somewhere.

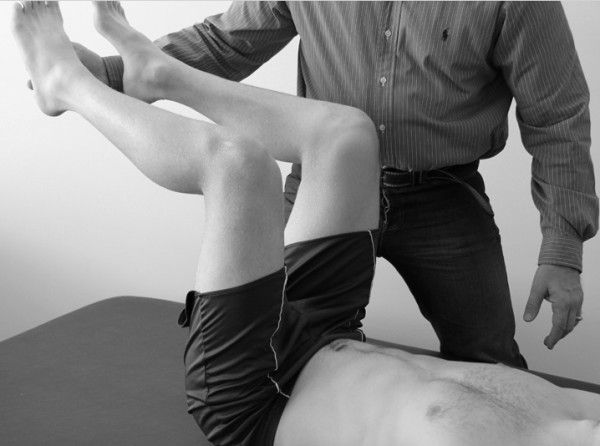

Much of the coursework we did was on learning how to access these patterns, with position-specific responses and challenges, and then how to utilize those concepts to move weight from point A to point B. Dr. Ulm acknowledged that at a certain load, “normal” patterns have to give way to other positions and patterns that can assist to move more weight, especially if that’s the main goal. While a neutral spinal position may be required to squat a non-maximal weight, a more extended spine may be required to move a higher relative load for competition purposes.

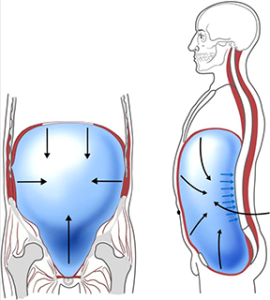

Image from www.rehabps.com

Hard low back extension

While max loading may require specific adaptations to patterns or positions, the rest of the time spent at non-max should default back to a lower energetic state where all muscles contribute evenly to basic processes like breathing, mobilization, and stabilization of the joints.

Being able to grade muscle contractions and intensities in various positions under different loads are basic functions of muscles and stabilization patterns, however especially in the fitness and strength populations, the ability for a muscle to exist in only “ON/OFF” makes it difficult for some to temper their contractile efforts to match the demands placed on them without overworking or defaulting to some compensatory patterns.

Imagine using a max effort deadlift strategy of positioning and stabilization to tie your shoes. Everyone would agree that shouldn’t be too difficult or cause someone to black out from exertion, but it’s a difficult line to walk when you’re always being coached to get tighter, stiffer, or more forceful in how you brace.

Breathing to produce depression of the diaphragm, expansion of the abdominal wall without relaxation, and creating a stable body in a challenged position can have some significant benefits to a lot of movements and systems other than just respiration.

A concept I’ve used in workshops and that was echoed here is that proximal stability produces distal mobility. Stability in this sense isn’t about non-motion, but about controlled positions exposed to force. There’s always some micromovement of the spine and other joints during every task we ask it to perform, so the challenge is to do those tasks within a range of what could be deemed “optimal” based on performance outcomes, reduced risk of tissue damage, and an absence of less desirable compensatory patterns.

Because of the benefits to this concept of stabilization, DNS seemed to compliment a lot of other thought processes on developing stability, mobility, and control through ranges of motion. One attendee theorized that DNS worked really well for the torso, and FRC concepts works really well with the limbs. Blending the two together seems to make a lot of sense in a training scenario.

There’s obviously a lot more to the depth of the DNS systems than could be covered in a single weight lifting workshop, but it was a good overview of their exercises concepts and how to apply them to compound lifts in the vein of both performance and motor learning/rehab. It’s all the same anatomy, so it’s simply how it’s used and when it has to be adjusted to make the benefits to the individual as high as possible with minimal risks.

The basics of the postures use can be very rudimentarily summed up as “get into position –> stay there –> breathe and own it.” As you introduce segmental motion into this summary, the goals still remain the same of using the positions, owning them, and breathing through all respiratory centres effectively. As loading or endurance requirements increase, you work to the point of failure to maintain position and reset to prevent training into secondary or less desirable ways to maintain those positions or loads, lather, rinse, repeat.

After taking the DNS Weightlifting course, I’m very interested to take further progressive courses in the DNS system to see what I can take away and what I can add to my clients training to help them see better results.