Disqualify the Exercise, or the Client?

There’s been a lot of controversy in the training world these days about bad exercises, specifically movements like overhead pressing and crunching. On top of that, there’s still the old debates of your knees not going past your toes with squats (for my opinion, see above), eggs increasing your cholesterol, pink dumbells being at all useful for something other than a door stop, and high protein diets wrecking your kidneys and making you have the runs. Now while I will save the boredom of getting all geek-tastic on the biomechanical models of each movement, why they are beneficial and why they are possibly detrimental, I figured a less coma-inducing read for everyone would be a simple question posed to the entire fitness industry:

Instead of decrying an exercise, why not debate how to assess the person to see if the exercise is right for them or not??

The funny thing is that when you ask a room full of experts about the merits of these “dangerous” exercises, many of them will say that there is no such thing as a bad exercise, just some people who may not be able to handle the exercise and have an increased risk of injury as a result. I’ve heard Stuart McGill say this about crunches numerous times, and he even has his own version of crunching that saves the spine. His big beef is with the wrong exercise for the wrong person with the wrong technique, and I would agree.

The major issue with crunching is that it puts the spine into a flexion biased posture without any co-activation from the extensor groups, which can increase the pressure on the intervertebral discs and increase the risk of damage, possibly even of herniation. The worst people to program crunches for would be those stuck in a flexion biased posture, posterior pelvic tilt, thoracic kyphosis, those with degenerative discs and spinal osteoartritis, and obviously those who are still in pain of any kind.

The downside here is that even if someone is not in pain, there is an increased risk of having some sort of issue with the spine. In a fantastic study in the New England Journal of Medicine by Jensen et al, (1994), the study took MRI’s of people with no history of back pain, and found that 52% of all subjects had significant indications of disc bulges, and 14% had degeneration of the annular rings. That’s a whole lot of walking wounded wanting to come into the gym and get their swole on, yo.

With overhead pressing, the big risk is with people who have weak scapular rotators, insufficient T-spine extension, anterior head position, and weak or damaged rotator cuffs. If they have any presence of AC joint restrictions or calcification of the joint surfaces that may restrict movement, having the arm rotate overhead will produce some kind of compensation, and typically make the exercise less than ideal.

Another study looked at the results of MRI’s on shoulders of individuals without any shoulder pain by Sher et al (1995) in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. They found full-thickness tears to the rotator cuff in 15% of the 96 subjects, and partial thickness tears in 20%, with an increasing incidence with age. Remember, these are people with NO PAIN WHATSOEVER!!!

The point of showing these two studies is that we can’t simply assume someone is healthy because they say they have no pain and want to work out. We have to assess them first and find out if they have some specific areas of concern that may limit the exercises we can do with them. This can be pretty difficult in a self-assessment to determine whether your shoulders are beat to hell or if your low back mechanics are ideal or not, so finding someone who can check these out for you is almost a necessity before starting a resistance training program, and can also help to determine if you’re getting ahead or setting yourself back by doing certain movements.

Now for the ray of good news.

Are there any specific instances where using a crunch would be beneficial? Absolutely! Let’s say someone has some anterior tilt, weakness in their rectus abdominis, and are sitting with some lumbar lordosis. The spine is essentially stuck in extension, and performing some modified short range of motion spinal flexion movements would be appropriate.

A funny thought about the spine during flexion that always made me laugh a little was the thought that there is a finite number of cycles of spinal flexion an individual can go through before the disc will herniate. This sounds incredibly similar to the thought process in cardiology that considered the heart to have a finite number of beats and that they shouldn’t be wasted on exercise.

Is the spine actually different?

While it may not be as good as other exercises, the point is that a crunch would be acceptable in the right person.

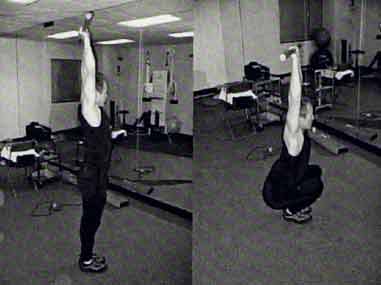

What about overhead pressing? Sure, most people walking into the gym wouldn’t have the ideal mechanics to pull one off with minimal risk, but there are variations, like a hang snatch and a push press that can still give you the ability to do overhead movements while reducing risk. Plus, a hang snatch, done correctly (read: not done in a flailing windmill fashion) is pretty badass when pulled off in a gym anywhere.

So instead of trying to decide which exercises we can’t do for everyone in the history of ever because they’ll immediately make you broken and stuff, let’s focus on trying to qualify those who can actually DO the exercises safely, then design a properly balanced program that allows for adaptation without compensation, THEN actually teach the exercise correctly, and make sure we correct technical faults as they come up. That’s the job of a trainer after all, isn’t it?

In case you’re wondering, yes, I do program crunch variations for certain clients, as well as overhead pressing variations (similar to the ones outlined above) for certain clients. Key word here is CERTAIN clients. The ones who have all the necessary pre-requisites to qualify them to do the movement, and where their goal set lines up with having them perform the movement.

What do you think? Leave a comment below with your opinion and let me know what works for you and what doesn’t.

2 Responses to Disqualify the Exercise, or the Client?