Deadlifts and Disc Herniations: Part 1

Each day I get a couple of questions from different people who like reading the demented ramblings I put up on this here website. Now while I absolutely love being able to help as many people as I can, and am more than willing to give away free advice, there are some situations that I feel can’t be covered in a simple email response.

Here’s a recent question I had in my email inbox:

I’ve been following your blog for a while now. I find it particularly interesting because I’m 18 months post herniating L4, and ~36 months post S1. Rehab’s turned me into a gym addict.

I started out deadlifting shortly after getting the clearance, terrified at about 15lb, but made it past my body weight a couple of months ago. That was when I figured it was time to try to progress to the other variants. That’s where it’s gotten hard again.

I read that Boyle recommends Bulgarian split-squats and trap-bar deadlifts for safety, so I tried. The problem is that I have no power that low. If I back the weight off to where I can get it off the ground, then completing the range of motion’s too easy. The racks at the Y don’t go low enough to get the weight below my knees.

Conventional deadlifts are pretty much impossible. The last option I know to try is sumo deadlifts, but am wondering what happens if that proves tricky. How do I get that range of motion working?

First off, I have to hand it to anyone who takes charge of their own health and WANTS to get after it in the gym to make themselves feel better, rather than resorting to surgeries, medications, and becoming part of the system. Big props for getting under the bar again.

Second, I have to say that I’m going to tread lightly off the start, because not knowing whether this specific instance was a herniation into the central or lateral foramen, which would affect the movement patterns that we could use as well as the pain referral pattern, as well as any other necessary info regarding the injury, surgery, or rehab protocol used, I’m pretty much making assumptions about everything I can think of, so I’m going to write this as a piece dedicated to being able to regain the ability to continue deadlifting for disc issues and low back pain in general, as well as ways to progress or regress the movement pattern to make it accommodate the injury. Sounds like a basket of fun, right??

Second, I have to say that I’m going to tread lightly off the start, because not knowing whether this specific instance was a herniation into the central or lateral foramen, which would affect the movement patterns that we could use as well as the pain referral pattern, as well as any other necessary info regarding the injury, surgery, or rehab protocol used, I’m pretty much making assumptions about everything I can think of, so I’m going to write this as a piece dedicated to being able to regain the ability to continue deadlifting for disc issues and low back pain in general, as well as ways to progress or regress the movement pattern to make it accommodate the injury. Sounds like a basket of fun, right??

I would definitely advise anyone out there to get clearance from a medical professional before beginning this kind of workout program for a back injury, as each situation will present differently and may not work for everyone. For instance, the pain down the back of the legs symptomatic in individuals with disc issues can also be present in people with spondylo, stenosis, and a few other issues, but would require a completely different program than I’m going to outline here, so get it checked out, folks.

Now before I start, let me remind everyone out there of something pretty fantastic that happened last month. After battling low back pain for the better part of a decade as the result of bulged lumbar discs at three levels, partial thickness tear to the QL on the right side, and an SI joint subluxation, I finally hit my goal of a 405 deadlift, which means (in my mind anyway) that this back injury is something I can conquer and essentially make my bitch.

So here’s the fun components that compound the issue revolving around disc herniations and deadlifting. 1. The glutes will get tight and limit hip mobility as they try to give some level of stability to the pelvis and posterior fascial chain, and as a result pull the hips into posterior tilt. 2. The abdominals will get tight to try to provide some stability for the spine. 3. These two combine to pull the spine into flexion, which will put the spine under more pressure to push the disc posteriorly. 4. The spine has almost no structural support at this point, so its’ relying on nothing but muscular and fascial support to do the job, and it’s never enough to make up for the lack of structure.

The INSTANT you start to move into the start position to pick up the bar, you’re already exposing your spine the kind of forces necessary to cause a further bulge. That’s why whenever I see shit like this in the gym I want to pour hot coffee into my eyes:

SO before we start to even consider performing a deadlift, we have to address the limiting factors: mainly the pelvic mobility and spine stability and position. The good thing is that a lot of people have similar issues, but aren’t weighted down by the extra burden of mind-numbingly crippling pain whenever they move.

SO before we start to even consider performing a deadlift, we have to address the limiting factors: mainly the pelvic mobility and spine stability and position. The good thing is that a lot of people have similar issues, but aren’t weighted down by the extra burden of mind-numbingly crippling pain whenever they move.

If the glutes are more cranky than the flower girl in the royal wedding, there’s definitely going to be a mobility issue there. I’ve touched on the concept of how the hamstrings can be tight from holding tension due to spinal instability HERE, but it also rings true for the glutes. From an anecdotal perspective, every time I’ve had any type of problem with my back, I’ve found using a McKenzie stretch works perfectly to put the spine into extension and allow the glutes to relax.

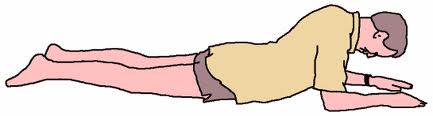

For those unfamiliar, the basic McKenzie stretch involves paying on your stomach and propping yourself up on your elbows to put a passive extension stretch into the spine. By hanging out here for a few minutes at a shot, the muscles can relax enough to let you move freely and actually begin to train them again, rather than fight through a bullet-proof layer of body armour that your hips put up to keep you from screwing yourself up further.

Once the muscles are relaxed enough to allow some movement, we have to start actually moving!! Step one will be to get the core muscles to work right again by giving them the job of stabilizing against external resistance. This is where the concept of “Anti-Abs” comes in to play, as the purpose here is to resist movement while external forces are applied to the body. Since the issue with a herniation is the lack of stability in the specific areas of the spine, the abs have to work extra hard to keep the spine together.

Once the muscles are relaxed enough to allow some movement, we have to start actually moving!! Step one will be to get the core muscles to work right again by giving them the job of stabilizing against external resistance. This is where the concept of “Anti-Abs” comes in to play, as the purpose here is to resist movement while external forces are applied to the body. Since the issue with a herniation is the lack of stability in the specific areas of the spine, the abs have to work extra hard to keep the spine together.

Next up, we have to make sure the hips can move without causing the spine to go into flexion. Squatting will be the biggest step to getting a bullet-proof deadlift after a back injury. This doesn’t mean that any Johnny Meathead with a disc bulge and an intestine full of NO Xplode should go and throw a plate on the bar and start ramming out back squats. It means the first step should be body weight squats to femur-parralel depth with no pelvic tilting into posterior positioning, which would put more pressure on the discs.

Squats are important in this stage because learning how to activate the core stabilizers while performing a hip mobilizing movement will be paramount to being able to deadlift. Another key is that a squat limits the amount of shear force on the spine, and helps to teach the body to maintain neutral or even a light extension while moving through hip flexion.

By maintaining the spine in a vertical allignment, you limit the amount of force directed through the spine, specifically in the form of torque and shear force. The closer the weight is to the body, the lower the force on the lumbar spine. Once you start to get the shoulders ahead of the centre of gravity, you start to exponentially increase the amount of force on the lumbar spine, which means for the first phase of training the weight spine should be held as vertical as possible.

So with part one covering the basics of spinal stabilization and the need for training the squat pattern to maintain a vertical spine, we’re going to go through some more progressions in Part 2 tomorrow. In Part 2, we’re going to go through some deadlifting progressions that can help to train the pattern leading up to the conventional lift from the floor.

For more information on how to train low back injuries with specific focus on the fascial connective chains, I would strongly recommend getting yourself a copy of Muscle Imbalances Revealed. I’ve had probably about 30-40 people email me and say they got so much out of the presentations on this series that they helped themselves end their back pain or helped their clients move better than they ever have, so get your copy HERE.