Anterior Humeral Glide: Preventing it to Keep You In The Game

I’m sure the title of this post alone is about as sexy was watching Kris Jenner clip her toe nails with one foot on the toilet and simultaneously waxing her upper lip, but it’s a common technique and positioning fault that has a lot of implications to keeping your shoulders healthy while lifting. Also, if your shoulders currently hate life when you do things like chin ups, rows, bench presses, or other movements that could cause the front of your shoulder to get sore, this could be valuable info to help you not feel like you just sand blasted under your front delt from just a warm up set.

Anterior humeral glide is a fancy pants way of saying “the pointy shoulder bone done gone forward when you did the thing.” That’s essentially red neck speak for when the upper portion of the humerus moves forward in relation to the shoulder socket itself with movements where the arm is brought towards the body and even behind it. A classic example is a row movement, or the bottom of the bench press.

When this small little movement happens, it’s usually the result of a cluster of things pushing it in this direction. First, a portion of this is due to the shoulder blade being in a position where it’s tipped forward versus sitting flat to the rib cage. This usually happens if the person is rounding their upper back and flexing their thoracic spine. It’s also common with people who use their upper traps for everything and don’t know where their lower traps or serratus are at all. These three muscles combine to help produce a lot of the shoulder blade stability for big movements, so if one or two aren’t pulling their weight, the shoulder blade will wind up in a new position to accomplish the goal of lifting mind-bending weights and getting all jacked and swole.

That forward tip of the scapula is also usually combined with some degree of protraction, where the shoulder blades slide forward on the ribs versus pulling back and together. If you’re doing a row movement, for example, the end result should be the shoulders being pulled back and down, not up and forward.

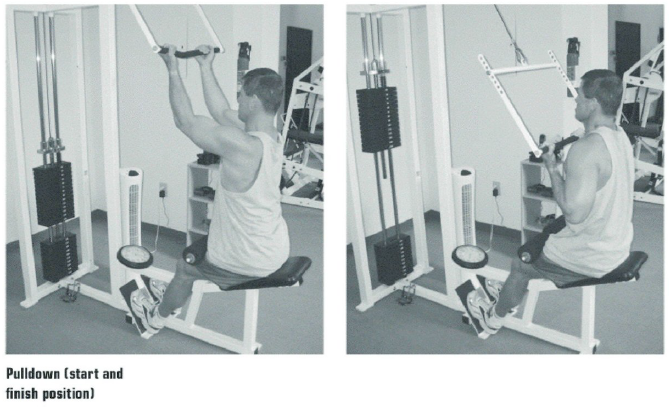

Because of this forward tilt from above as well as a protraction from the side, the humerus can’t easily sit inside the cup of its socket, and winds up gliding forward to accommodate the arm being pulled back behind the shoulder blade. It will often look something like this:

Notice how in the pic on the left, in relation to the ribs, the shoulder looks like it’s tilted forward, and the upper portion of the arm is actually ahead of where the shoulder socket should be, and the elbow is behind. The second picture shows a shoulder not going through that anterior glide, where the head of the humerus is being pulled into the socket versus pushed out of it.

Now this by itself isn’t the end of the world, nor would it be as bad as whatever the hell the Indianapolis Colts tried to do against the Pats this week with that 1 on 5 lineup on 4th down, but it can cause some irritation to structures that have to pull double duty.

One of those structures is the biceps tendon, which wraps along the upper part of the humerus and attaches to the shoulder blade. This long head of the biceps essentially acts as the safety net for the humerus in this position, helping to keep it from sliding entirely out of the socket. The downside is that it’s not designed to have friction or horizontal load placed on it, so it can wind up getting irritated, sore and inflamed. In some cases, this bicipetal tendinitis that could result may wear away at the tendon enough to require surgery to fix.

With movements like bench press, this is a common feature if the person lays on the bench with their shoulders spread wide versus being pulled together tightly and with some consistent effort to prevent them from sliding out from under the ribs. If the shoulders are positioned so that the back is flat against the bench and the shoulder blades are out in a protracted position, lowering the bar will cause that anterior glide as the bar gets to within a few inches of the chest. As the bar gets lower, more gliding happens, and more pressure is placed on that vulnerable tendon and other anterior shoulder structures.

In some people who have this anterior shoulder pain, fixing the issue could be as simple as getting them to avoid positioning that would cause an anterior glide of the humerus. A portion of this would come from 3 main things:

- Posture during the exercise. When doing any movement where the shoulder is pulled back into extension, it’s important to think of keeping the thoracic spine in a more extended posture compared to flexion. This helps the shoulder blades to retract and depress during rowing movements, and prevents that forward tilt and protraction that can lead to anterior glide.

A few simple drills to work on thoracic extension if you’re lacking:

- Make the movement for a row come from the shoulder blades. This ensures you’re actually making your shoulder blades move versus just getting the weight from extended elbows to your chest. Additionally, thinking of getting the shoulder blades to slide into your back pockets can make you feel the working muscles of your lats a lot more.

However, when doing pressing movements the rules are reversed. Try to get your shoulder blades to sit as flat against your ribs as possible, and do the pressing with just the shoulder joint and not from the shoulder blades. This will ensure you maintain a decent position to resist sliding into that anterior glide position, plus you might just lift more weight since this is a classic powerlifter cue.

- Shorten the range of motion if needed. Where a lot of people get into trouble is trying to pull their hands back too far, and wind up doing some version of an initial muscle up versus a row. This commonly looks like the individual has rowed as far as possible, and then to continue the range of motion now they’re rotating their shoulders and elbows to allow them to almost press the weight into them further. This is most clearly seen when beginners use a lat pulldown machine and wind up pulling the weight to their belly button versus just stopping for the love of God at their collar bones.

- Use less weight. I know, it’s sacrilege to say to “control your bro” and not max out on how much you lift every single time. Yet in my defense, I would say if you’re having some anterior shoulder pain, lifting heavier with piss poor technique that is likely causing that pain likely won’t become some magical body butter that makes the boo-boo go away. If you have a headache from slamming your face into a wall, continuing to slam your face into a wall won’t make it any better, no matter how much Tylenol you take or how much tiger balm you rub into the area.

Reducing the weight you use can help to re-learn the positioning and get the shoulder blades to retract and depress more efficiently, which will likely wind up causing you to feel your low traps and lats more anyway compared to doing your quarter shrugs of death you were previously doing.

This is a common technique fault I see a lot with people, and one of the simple fixes that can have a big impact on how your shoulders feel during exercise and through the day in general. While it may not be as sexy of a topic as something like “50 fitness models show their glute workouts in their skimpiest booty shorts,” I think more people will get better use out of this. At least in a PG manner.

10 Responses to Anterior Humeral Glide: Preventing it to Keep You In The Game