All Things Thoracic Spine Part 1: Functional Anatomy

Last week was an epic fail on the blogging front for me, which makes me look like a raging clown-punchers for leaving all my peeps hanging. My bad. Hopefully today I’ll be able to make up for it by giving you some solid info on thoracic spine functional anatomy, assessments and exercises. Because this is going to be so epic, I’m going to break it up into a three-parter, which means you’ll be able to digest it all much more easily, because much like a block of cheese it’s best to get information in small quantites over a longer period instead of gobbling it all up in one sitting.

Please be aware that displaying this information to others may result in a significant increase in attention paid to you by members of the opposite sex (or same sex if you swing that way), and might also lead to feelings of superhero-ism and invincibility. With great knowledge comes great power, so make sure you wield it responsibly, or at least in a way that gets you more dates or lets you earn mad skrilla, yo.

Functional Anatomy: Why The Hell T-Spine Mechanics are Important

Here’s the gist of functional anatomy. I’m not going to bore you with the details of how many degrees of rotation each vertebrae has (7-9 degrees), or the bony components that make it kick ass, or try to make myself sound super-serious and book smart (poop), because it’s more important to know what the hell all of that means when it comes to getting your swole on and preventing you from having a soul-draining injury for the rest of your life from not training like a jack-bag. Sound good? Thought so.

The T-spine has three primary roles: attachment point for the ribs; attachment point for the scapula; and mobility for the ability to flex forward, extend backward and rotate. We’ll talk about each three today, as well as what components need to be involved with a training program or assessments.

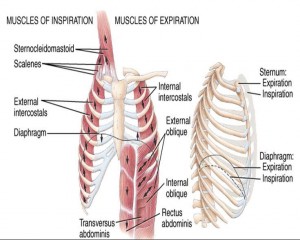

The ribs attach to the entire length of the thoracic spine, which is one of their defining physical features compared to other segments of the spinal column. The ribs are interconnected by intercostal muscles, and under the direct influence of the respiratory muscles like the scalenes, diaphragm, rectus abdominis, and to a lesser degree the remainder of the core musculature.

One aspect that gets over-looked by a lot of trainers or therapists is the role of breathing in upper body function (as well as lower body, but we’ll cover that later). Think of Janda’s classic Upper Cross syndrome: he states that the upper body has a definable pattern of tightness and shortness in the pec minor and cervical extensors, and long and weak lower traps and deep neck flexors. That’s all well and good, but working on re-aligning this imbalance really doesn’t benefit people all that much. I fell into this thought process with a lot of clients a few years ago, and got almost no results with them, which showed that this wasn’t really the problem, was it?

Without a doubt, Janda was decades ahead of his time, but this isn’t a complete picture of the common postural dysfunction. It doesn’t take into account the role of the ribs or breathing mechanics on the posture. If the intercostals are tight and the diaphragm is depressed (we see this in skinny people with a bit of a belly, especially in the upper abdomen), they literally won’t be able to get their spine to straighten up to get the shoulders to move properly or to get their neck into neutral alignment.

When the intercostals contract, they pull the ribs together and cause the T-spine to flex. Held chronically in this position, they won’t be a major player in respiration, meaning the entire role has to be performed by the diaphragm. You can see this in a postural assessment when someone breathes and the only part of their body that moves is their abdomen. Normally, there should be an expansion and collapse of the upper ribs, lower ribs, and abdomen with deep breathing, meaning all the muscles of respiration are working the way they should. Here’s an example of someone who did all her breathing through just her upper ribs, not through the diaphragm or lower ribs. Coincidentally enough, when she ran she would get cramping through her upper ribs and collarbone as those respiratory muscles worked like crazy to keep her sucking air.

When one center isn’t doing its’ job, the others have to pick up the slack. This is one reason people get side stitches or neck cramps when performing hard anaerobic work: their ribs aren’t moving properly and either their respiratory muscles get overworked (scalenes for the neck cramping, and diaphragm & external obliques for the side stitches).

Now let’s say someone has a lean to one side and an obvious flare to their ribs. Odds are they’re probably not just striking a pose to look THAT gangsta, but rather it’s the position they have the least discomfort for breathing. The side they’re compressing isn’t as mobile, so they collapse it and force the other side to do the work.

The jury’s still out on whether posing with the duck face is actually a postural issue or whether it’s a form of evolution in reverse. Maybe it’s a way for dumb people to recognize each other and build a super race of humans who prefer to run their heads into walls repeatedly? That would explain the Kardashians.

If the thoracic spine isn’t able to get into extension, your ability to rotate and glide your scapula becomes impaired, which means your rotator cuff problems have less to do with the actual rotator cuff than Mike Tyson’s facial tattoo has to do with his tribal origins in Samoa. An easy test you can use to prove this is try to sit up as tall as possible and bring your arms up overhead in front of you. Pretty easy, right? Now slump like it’s going out of style, and try to do it again. Did you get anywhere? Probably not, and if you’re like me you probably got a little dull ache in your shoulders as a result.

Scapular mobility hinges on the thoracic spine’s ability to create extension and some rotation (in the case of single arm movements). If the T-spine isn’t doing its’ job, it’s sort of like trying to build a house on a foundation made of swamp: it’s going to collapse.This becomes even more apparent when we see the fact that elderly people have a greater degree of disc compression and degeneration that younger folks (that’s why they look shorter over time and begin to have a forward flexed posture), and why there’s an increased incidence of rotator cuff tears (almost double in 60 years and older compared with those younger than 40), even in asymptomatic people.

This is another reason I’m not a huge fan of overhead pressing, as a lot of people don’t have the ability to get the right mechanical alignment to do the movement without increasing the risk injury. It’s also a reason why Crossfitters tend to get more shoulder injuries, as for some reason they insist on jutting their heads forward on their overhead presses and overhead squats, which leads to some form of compensation in their T-spine and scapular rhythm, increasing dysfunctions. Not all of them, mind you, just the ones who want to get injured.

One reason we get into this situation is due to the level of sedentary life involved in our daily activities. We sit in a flexed posture so much that the ribs have to develop some adaptation by shortening and getting stiffer to help keep us in that posture for longer periods of time. We’ve also altered our breathing as a result, forcing our upper ribs and diaphgragm to do all the work.

It’s not an issue of a single muscle or segment of the body being dysfunctional, which is a common thought process of our reductionist method of assessments, but a convoluted systematic series of adaptations and compensations that leads to dysfunction, and unraveling that mess one component at a time can be chaotic and make you feel like hugging your knees in the corner while slowly rocking and sobbing quietly to yourself.

To look only at the ribs as one of the issues for any thoracic spine dysfunction would also involve dismissing the role of pelvic tilting to the function of the core musculatre, and their roles “up the chain” which could affect the thoracic spine. Which one is more important? None are more important, as they all play a role in leading to the problem, which means a program that focuses on addressing everything instead of focusing on one part or another is going to be more effective in the long run.

Later this week, Part Two will talk about different assessment techniques you can use to determine whether the thoracic spine is rock solid or full of issues.

I talk about thoracic spine anatomy, assessments, and corrective exercises in Post Rehab Essentials, as well as ways it interconnects with all other issues seen in the body. For that reason, plus probably a dozen others, you should get a copy and get your learn on.

50 Responses to All Things Thoracic Spine Part 1: Functional Anatomy