The 3 Main Goals of an Assessment

When I have a client or perspective client come in for an assessment with me to begin a training program or to simply get advice on what they should do to get the results they’re looking for, it typically comes down to a couple of fairly simple elements that can be potential unending rabbit holes of Alice in Wonderland style depth and breadth. For today I’ll keep them pretty shallow and concise because it’s Thursday and no one wants to think hard on Mini-Friday.

Consider an assessment as sort of an exploratory investigation of what’s currently going on with the person in front of you, and looking to figure out how to draw a line of action from where they are to what their specific goals are. If you want to be a competitive powerlifter at any level, do you have some idea how to do the main lifts? If you’re a relatively older professional athlete looking to stay competitive, what is your injury history like and are there elements that are holding you back from playing at your best? If you’re looking to lose weight are there elements of your diet or lifestyle that are easy to switch up or that would take a considerable effort, and are you healthy enough for a calorie burning workout with minimal risk?

So let’s outline the big 3 goals of any assessment and break down what they’re trying to find, plus how you can use them to your advantage in your own training.

#1: What is your goal, and where are you in relation to it?

This may seem like an obvious point, which is why it comes first. Often the goal will dictate the type of training program to be done, the commitment required, and the prospective timeline of training.

How far away you may be from that goal will also make a big difference in what the training looks like and the calendar to get there. If you want to tone up for a wedding that’s in 6 months versus 6 weeks, there’s going to be a significant difference in the focus and relative extremes of how to get there. Setting up a quadrennial plan to prepare for the next Olympics will also be very different than a peak phase to get ready for a championship in a couple months.

There’s also the element of reality that has to be discussed. Someone who is 5’2″ may not be able to go very far as a basketball player, regardless of how skilled and strong they may be. Coaches and talent scouts will simply say “you’re good, but you’re too short,” and give a pass. The same stat line coming from someone who is 6’2″ or 7’2″ would be very different in terms of how they’re recruited.

Likewise, looking to do something very common like running a first marathon can be a considerably challenging goal. Typically, if you haven’t begun running or had some decent history of running, it would be about a 2 year period to build up your body to manage the mileage required to run a marathon well enough to not suffer significantly along the way. Where people tend to get into trouble is thinking they’ll give it a go after only running for about 6 months, and as the mileage increases beyond their tissues ability to handle it and recover adequately from the stress of their training, they develop overuse injuries that prevent their ability to train. Tissues take time to train.

When it comes to achieving specific goals, there’s always a relatively well established training program that works appropriately across a large segment of the population that is looking to accomplish similar goals. Bodybuilding style programs are pretty well established (overload specific muscles, recover, do it again), as are powerlifting programs (train the squat, bench and deadlift, add weight as needed), medical rehab, sport performance, running, mobility, and everything else. The specifics of the program can be altered, but often the general outline remains the same for the specific goals. They’re usually based on principles like Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID), Wolf’s Law (tissues adapt to the stressors they’re exposed to), Law of Repetitive Strain (tissues exposed to stress will adapt, too much and they’ll adapt negatively, not enough recovery time and they’ll adapt negatively), and the Bro Code (no curls in the squat rack).

So understanding the goal and the type of programming they’ll need to get to where they want to be leads us to the second component of assessments.

#2: What Can You Do Today?

This phase of the assessment will be geared entirely around the goal the individual has, and how well prepared they are to train for the goal they’re choosing. Some of the big things that cross across a lot of the specific instances remain, even if the goal set is very different:

- Do they have the cardiovascular ability to do the training or prepare for the goal at hand?

- Do they have the body awareness to engage in the training program or do they require some regressions/progressions?

- Do they have the specific joint ranges of motion to do the training program?

- Do they have the required skills (if any) to do the training for the goal? (skills may come down to things like throwing a ball for a baseball player, skating for a hockey player, or doing a clean & jerk or snatch for olympic weightlifter, plus others)

Each element could involve dozens of different assessment types and classifications, all valid but specific to the specific population or goalset. For instance, a treadmill walk test would be fantastic for someone who was under medical management for cardiac issues, but woefully underwhelming for a sprinter or soccer player.

A bodyweight squat assessment would be fantastic for someone recovering from a hip or knee replacement, but not specific to a powerlifter or olympic lifter.

a 5 mile run test would be appropriate for a marathon runner looking to determine their training splits, but impossible for someone with COPD.

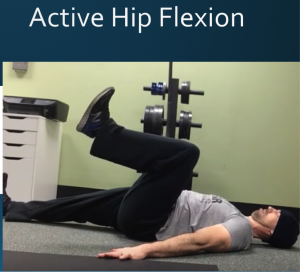

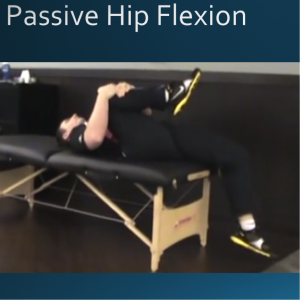

When looking at range of motion, it could be an important distinction to see whether the individual has the passive range of motion available to do the movement or skill, and also whether they have the active range of motion throughout that entire range as well.

If there’s a difference between a full passive range of motion to perform a specific task and their ability to actively move through that range of motion, it should be something you address with your training program. Here’s a live example from the L2 Fitness Summit video series:

A joint with the ability to go through the range of motion necessary to perform a specific task, as well as the strength and motor control to use that range effectively, is one of the first requirements to any training program. It’s tough to get white lights in a powerlifting meet if you can’t effectively squat to depth because your hip sockets don’t allow that much hip flexion, but it’s also tough to be a strong runner if you lack hip extension for a strong kick. Slow runners typically have zero hip extension, so to get any kind of kick, they’ll either have to have a higher cadence, or extend through their low back to get the necessary range, neither of which is a beneficial strategy long term.

Knowing whether the individual has the specific skills for their goalset comes down to having experience with that goal, coaching that would benefit them, and how to connect the dots between what they’re capable of and where they need to be. I’d love to say I’m skilled at everything, but there’s some things I have no experience with, and have to tag out to someone else who specializes in that area. I’ve never played baseball, so learning throwing mechanics is something outside of my experience, but I have done some olympic lifting myself, as well as taken a couple of coaching courses, so I’m comfortable working with entry level skillsets, but not quite olympic caliber competitors. Find someone with the skillset to make sure you can get the benefits you’re after.

Now we get to part 3, which is often unfortunately overlooked.

#3: Red Flags

I work with some medical populations where a workout that’s too intense could actually kill them. Others with specific injury histories could be significantly impaired by a workout that’s slightly beyond their comfort, so understanding where to draw the line becomes a pretty major thing for them. Others may not tolerate squats well but can lunge or deadlift like a mofo, so picking out what movements they excel at and movements that may require some medical attention can help me design a more effective program that doesn’t cause as much of a problem down the road.

A basic element that can help determine some red flags in an individual is a sub max cardio test looking for any potentially negative symptoms. A basic walk (or jog) and seeing if the individual gets any chest pain, wheezing breathing, change in color other than pink or red, or anything that could indicate they’re in distress can be simple to start and quick to end, and give a lot of info on whether a workout program is appropriate for them or not.

Along with this, looking at how their heart rate increases from rest with the addition of a workload and then how quickly it returns to resting after you finish the work can be indicative of health or dysfunction. When someone stops working, their heart rate should return back to close to resting within a minute or two. If it stays elevated for a long time, it could indicate they aren’t tolerating the workout well.

These concepts are outlined and expanded on in my new video series the L2 Fitness Summit, along with hypertrophy training concepts programming and nutrition with Dr. Mike Israetel. The entire series is on sale until December 10th at midnight for $50 off the regular price (only $97), and comes with 11 hours of professionally filmed and edited video, continuing education credits through the NSCA, and lifetime access through streaming instant video.

One Response to The 3 Main Goals of an Assessment