5 Coaching Cues to Immediately Improve Basic Movements

There’s always a fine line between doing an exercise well and doing it to make everyone in the gym think you’re trying to do a version of the Humpty Dance mixed with a grand maul seizures for time. I mean it would be easy to be a technique nazi about every single thing people do, but there’s some simple things that can help clear up a lot of basic movements so people can reap the best rewards with less effort and less mental stress as well.

Basic exercises are like specific skills in any sport, like dribbling or shooting a free throw in basketball. There’s not really much need to make them more challenging for the most part, but just to rehearse the skill to keep them somewhat fine tuned so that they’re almost automatic when needed. I could think of no greater travesty than someone who could only squat if they had double body weight on their back, which would account for all of 0.15% of the time they would likely need to be able to squat down in the rest of their life outside of the gym. It’s still necessary to have strength, but it’s also necessary to not need to use all of it all the time.

So with that said, let’s look at 5 basic exercises and a couple of simple cues I use to help people get the most out of them. These are cues I use all the time with my clients, and when all else fails thy seem to be the ones most clients respond well to.

#1: With Rows, Keep the head behind your chest

Many rowing movements involve the use of scapular retraction and depression to get the lats to move the weight. This movement typically requires thoracic extension to occur, as flexion doesn’t let the shoulder blades retract very well. Try it on your own. Sit up tall and extend your chest like you have something to be proud about and try to make your shoulder blades kiss. Pretty easy, right? Now slump like the weight of the world is slowly crushing your body, spirit and dreams and then try to get your shoulder blades to touch. Not happening.

When doing a row, thoracic extension is necessary to get everything moving well, and it becomes very difficult to get that extension with your head forward. Often a forward head posture on a row winds up with the shoulders being retracted through elevation instead of depression, which is great if your main goal is to have shoulders that look like they are a part of your ears and that you have no neck, but that’s not a hot look for the fall fashion season.

While I’m sure the concept of developing scoliosis AMRAP is appealing to some, by thinking of keeping your head behind your chest you wind up getting a bit more thoracic extension, and by default wind up getting your shoulders to retract and depress in a much easier manner.

#2: Make your chest the first thing to touch the ground with a pushup.

Pushups are kind of a weird exercise. I mean, you’re over the floor, pushing yourself up, and then for some reason lowering back down again. Most of the time if you’re face down on the floor, good things aren’t going to happen or haven’t happened to put you there, so getting off the floor and not returning is likely your best option, so doing an exercise where you repeatedly and voluntarily get into a somewhat vulnerable position seems fairly paradoxical.

Kidding aside, the pushup is fantastic for building upper body strength and endurance while also involving some degree of core stability with a stable spine that doesn’t resemble a lava lamp during the movement. That said, some people do a pushup with no regard to getting their pecs to work and simply bob along with their necks looking like they won’t be able to shoulder check for a week after each set, or do something like this guy.

I mean, if your goal is to rock out on Saturday night like no one has ever seen before, this might be right up your alley, but my guess is his upper body isn’t getting anywhere. Neither are his chances of landing a date from this group class.

So a simple fix that gets a lot of people into the right habit is to think of the chest as being the first thing to hit the floor. If you’re driving the work through your neck, your nose/chin will hit the floor way sooner than your chest, unless your name is Dolly Parton. If you have zero core stability and do more of a slinky pushup with hips and shoulders moving in separate rhythms, you’ll wind up with your hips hitting the floor first. Thinking chest will help to correct this, but will also be way more challenging as it requires more core strength to achieve.

#3: Aim your butt at your heels with squats

If you have trouble getting deeper into your squats, you might have some anatomical limitations at play, or could just be moving in a less than favourable direction. Many people squat like a version of a hip hinge, where their torso is folded over and their shins are so vertical they could double as flag poles.

Others might squat with so much spinal extension that their butts could double as a ski jump, or at the very least they could become a model for Insta-disc-delamination.

As a public service announcement, if your low back always hurts with lower body movements, you’re doing it wrong (or you have an injury you need to get resolved). If you get your fitness advice from someone who is only known to have a body part, look elsewhere.

A common denominator in either situation is a lack of knee or ankle flexion. It’s easy enough to consider a squat a triple flexion-extension movement (requiring flexion from ankles, knees and hips to lower down, and extension from all three to stand up), so using only one joint predominantly during the movement comes at the expense of the others, and will typically either limit your total range of motion, cause some pain somewhere, or both.

A typical cue I use to get people to understand where things should be going is to think of sitting your butt down onto your heels. This helps them think of not just the hips moving, but also that they need to lower their butt into the movement versus just pushing it back. A squat involves your butt lowering, a hip hinge involves sticking it out and snapping it shut.

While cueing this, as well as saying to keep the feet flat on the floor, full depth is usually much more of a possibility, as long as their hips allow it, but even then they’re going to have a better chance of using every inch they have available versus leaving it high and Instagram-worthy.

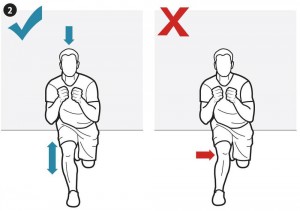

#4: For single leg work, grip the floor and think vertical line from ankle, knee and hip

Single leg work like lunges, step ups, or single leg balance work of any kind is typically more challenging for frontal plane stability than anything else for most people, so figuring out a way to improve balance plays a massive role in successfully not going shiny side down in the middle of a packed gym.

A big role in maintaining balance is controlling pronation and valgus collapse of the knee. For those who don’t know the fancy words I just used, that’s when your knee rolls towards your midline versus staying in a strong line and not collapsing towards your midline.

Valgus collapse is commonly believed to be a result of weak glutes which would help create more of an external rotation force to help control the knee from dropping into internal rotation, but equally important is having a foot actively involved in resisting pronation to help prevent the tibia from driving into internal rotation as well. This can be accomplished by cueing to grip the floor with the entire foot, so you actively try to keep the arch supportive versus falling faster than a soccer player tapped lightly while trying to draw a foul.

Keeping a strong foot means the ground impulse that would cause the initial pronation is controlled to a greater extent, meaning the knee is less likely to drive into valgus than simply trying to steer the ship with the glutes and a weak foot. From there, using some form of visual feedback like a mirror or simply looking down at your knee, try to keep a vertical line from the foot through the knee and hip. If you can visualize this line, it’s likely occurring and the amount of valgus is likely minimal. It could still be happening, but much less.

Another way to coach this is to use an external force that would push the knee further into valgus without active involvement from the individual. An RNT squat using an elastic would help in this regard.

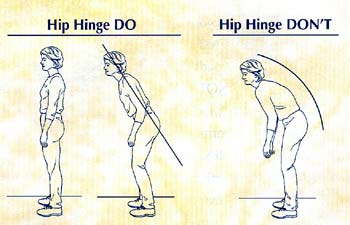

#5: Reach your butt to the wall behind you for the hip hinge

This is probably the most times I’ve referenced butts in a post. I’m starting to feel like Bret Contreras.

Hip hinge movements like a deadlift typically have people thinking of lowering their shoulders down to pick something up, essentially forgetting that their hips should be doing the movement instead of their spine. The hip hinge is essentially just that: moving from the hips and very little else.

Using a cue like “stick your butt out” typically only involves a seltering Instagram-like pose like the one shown earlier by the girl in pink, where the hips reach back but the spine arches almost painfully. Saying to reach back with your butt tends to get people to keep their spine a little more linear while also getting some horizontal displacement of the badonka donk. Essentially, with the exception of a very little bend in the knees, the hip hinge is all in the hips.

If an individual cant figure this out in free space, having them line up about 2 feet away from a wall and reaching back until they make contact helps a lot as well. They can’t round their back and expect to hit the surface of the drywall, and they can’t overbend the knees or they won’t touch either. It’s somewhat dummy-proof that way.

These 5 simple yet effective cues can help you get better results with the basic exercises you’ll use on a daily basis, while also making you have less to think about to get there. If you can make the movements more automatic, the less energy you will have to spend thinking through the mechanics and the more you can devote to the performance outcomes of each. Enjoy!!

4 Responses to 5 Coaching Cues to Immediately Improve Basic Movements