How Do You Program for That?

This past weekend Tony Gentilcore and I were teaching a 2 day workshop at The Third Space in London, UK to a great group of really switched on trainers. We covered the gambit from the basics of the squat and deadlift, to fixing wonky squat patterns, to breathing and how to implement it into a program, things like a turkish get up and swing, plus a bunch of stuff on assessments and the odd Superman & Game of Thrones reference thrown in for good measure.

We still have room for our Washington seminar in October, so you can register for that HERE, and we also just announced we’ll be heading to Los Angeles and will be fairly close to Disney Land. There may even be a few surprise “celebrity” appearances to that one, but you won’t know until you get there. Click HERE for more info on LA.

One question that came up during a couple points in the workshop was how to program all of the different things we were talking about. I mean, a sessions would be pretty cluttered if it were to involve a bunch of different mobility drills, breathing re-training, heavy strength work, loaded yoga, deadlifts on crack, and biceps curls until your face explodes in an homage to Raiders of the Lost Ark, right?

Maybe. It all depends on a bunch of factors.

First, I always say that before you look into how to program something for someone, you match the person to the exercise. I won’t get someone doing a barbell deadlift or kettlebell swing on day one if they’ve never touched a weight before, and definitely not if they have some form of mechanical low back pain. For them we may need to spend more time on low level core bracing training exercises, as well as some gentle hip stretches.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1wlGzAF” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/aj0wZeO9Nyk?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=aj0wZeO9Nyk&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep4772″ /]

Cogentally, this strategy may not be the most appropriate one to use for a football player looking to show up for training camp (and I realise the double meaning of football coming from North America and recently being in the UK, but they both have to show up for training camp, right?). As a result, no matter what exercise you are using, you have to consider the person who will be doing it, their state of training or possible injury risk, and what their goals are. If the exercise isn’t congruent with these facts, try something else.

So let’s say you have the average bloke who wants to gain some muscle, lose some body fat, “get fit” and get strong as an ox. He’s somewhat stiff all over and not terribly strong at all. How do you start? Funny enough, there are a lot of parallels to his type of programming as someone who is an elite level athlete in a multidirectional sport, as well as pretty much any other sport. Plus, it could feasibly parallel a geriatric client who is recovering from a hip replacement. The only difference would be the total loading, volume, accessory work, and relative intensity of the exercises used.

1. Preparation/Warm up

Everyone needs to get ready to train when they come into a gym or training facility. This could involve some light aerobic work, foam rolling, and movement prep, ideally all at the same time. There’s not really much of a point to increasing your heart rate only to have it come down with elongated rolling and slow ankle mobility drills followed by breathing on your back for 30 minutes, as that negates the heart rate response.

For someone who is a little more stiff and tight, they should start their workouts with some mobility work. Typically 5-10 minutes would be more than sufficient, focusing on the main joints and movements to be trained that day. For instance, if we were going to do deadlifts, we would want to work on hip mobility.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1wvV9Zf” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/iqiWCAidh20?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=iqiWCAidh20&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep6205″ /]

If we were training squats, I would focus more on the triple flexion movement through the ankles, knees and hips by using some progressive squat mobility drills.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1wvVxqA” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/2bcJNU8AuB0?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=2bcJNU8AuB0&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep2786″ /]

I’ve also found great success at increasing mobility with stability exercises.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1xOXeyr” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/it5HKA365gA?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=it5HKA365gA&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep9603″ /]

From there we could work on accessory mobility, like a thoracic spine movement.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1tqu59m” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/ImAGla9YQZE?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=ImAGla9YQZE&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep9031″ /]

Linking these kinds of exercises together with no rest between tends to keep the heart rate up from resting without being too intense for the individual. Using moderate reps (6-10 per exercise) can make the movements less than boring, and link together a couple of exercises(3-10 is usually sufficient) into a series to increase the time effectiveness of the entire thing. By the end the person should be lightly sweating, moving like Jagger, and mentally ready to dominate more plates than a dishwasher at Dennys.

2: Strength/Power

I always tend to put exercises in order of decreasing physical requirements. For instance, crunches or ab isolation exercises take very little mental energy, are very low demand for the central nervous system, and usually don’t require the person to be in a foaming frothing rage ready to wreak havoc and mayhem. As a result, they come last. The stuff that needs you to be jacked up and violent will come relatively early, such as heavy strength and power exercises.

These will always involve a slight build up in weight to get to the working sets. If you’re working on speed, the same idea applies, but with a gradual build up in velocity before ripping the space-time continuum with blazing distance over time.

For newbies in the gym, the volume and intensity will be relatively light. 3 sets of 6-10 reps would be very useful to help them learn a movement, get a training stress, and see some small adaptations. Their nervous system will need time to adapt to the new stress, so maxing out isn’t necessary at this point, and additionally they will need to allow their tendons and ligaments time to adapt as well. They tend to be very slow in comparison to muscle tissue, specifically because muscles have satellite cells that constantly put the muscle through regeneration whereas the ligaments and tendons don’t. For this reason, most guys who chase heavy strength have to take the occasional deload week where they cut back on the intensity and volume of their lifts, even if they feel awesome, so that their tendons and ligaments can play a little catch up with their muscles.

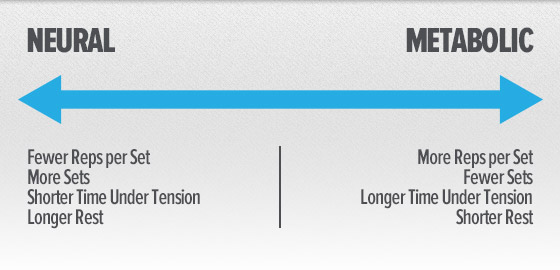

For more advanced trainees, they can tolerate loads closer to max and some increase in volume. there’s a big different between 3 sets of 8 reps and 8 sets of 3 reps in terms of the amount of weight you can lift and the effects on the body, plus the overall drain on the nervous system. This is why most people don’t get into the 8 sets of 3 type of training for at least a couple of years so that they can build up a tolerance to the stress of the heavier weights.

The movement is still the same, it’s just the approach and end outcome that differs. Master the movement first.

3. Accessory Work

In the decending order of workout importance, this would be the second goal after the strength work. Maybe it would be increasing upper back strength to help lock out deadlifts, or working on single leg work so that you could build some solid stability and leg strength following squats, or even work on balance and control or skill work for a specific sport. Whatever it is, the total demand on the system would be slightly less than the strength/speed work. Fatigue will play a small part here, so highly technical or mentally taxing work will have to be of somewhat limited volume. An example of this would be a front loaded skater squat.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1wvZ0Fy” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/XMqpXUtzkdU?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=XMqpXUtzkdU&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep5364″ /]

2 or 3 sets of 6-8 reps at this stage of the workout would be sufficient. If you wanted this to be of higher volume, placing it of higher importance in the workout would be recommended, so starting the main working sets following the workout with this kind of movement is a good idea.

Accessory work can also include some metabolic conditioning where movement competency is required. An example of this would be kettlebell swings, farmer carries, higher rep goblet squats, or any other number of exercises where a duration of a set would exceed 30 seconds. You could also work in short bout sprints, hill climbs, bikes, or any number of things where the relative effort to complete one rep is pretty low, but the accumulated fatigue doesn’t dramatically increase the risk of injury. This wouldn’t be the place to do high rep clean & jerks, not that there’s really any time to do them.

Following this would be anything else that you feel should be addressed that day. Maybe it would be additional core work, conditioning work, accumulated density (banging as many reps in a given time as possible), speed work with a compound lift using 50% of your usual load and working on fast contraction, or parasympathetically stimulating stuff like breathing or deep stretching drills. If the intensity is higher, the relative requirements of the movements should be almost idiot proof. This would be things like sled pushes, dragging, crawling patterns, or anything else that’s really hard to screw up.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1ww0aRB” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/Q5RJisj5sHs?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=Q5RJisj5sHs&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep1922″ /]

In anything you do, technical failure should come before muscular or metabolic failure. This means when the movement quality suffers or an ability to complete a rep without looking like a train wreck becomes impossible, the set is over, even if they only got 3 out of the 8 reps you wrote in your book. Adjust the weight, give them a pep talk and explain the goal of the exercise again, and re-coach them on how to do it better.

The number of reps a set can have before maxing out will also be an indicator of whether you have enough rest between sets or not. For instance, let’s say I’m being incredibly masochistic and want a client to do 3 sets of 20 reps of conventional deadlifts for movement training and metabolic conditioning. They get the first set of 20, rest a minute, swear at me inside their head (and maybe out loud), then hit up the second set but only get 17. If their volume drops off by more than 10%, they didn’t recover enough between sets and need more time before the next one. You can use this with speed as well. If it takes them longer to run the same distance, they aren’t recovered properly from the previous set.

This isn’t a hard and fast “law” of how to set up a program, but it does seem to pan out consistently, and with a lot of smart people using similar flows with small tweaks. For more information on how to program in a very highly effectively manner, I would recommend looking into Mark Rippetoe’s new book Starting Strength: 3rd Edition. It’s markedly different from the first 2 versions, and is well worth the investment.

Additionally, Mike Robertson and Joe Kenn put together a great video series outlining their programming methods in Elite Athlete Development Seminar.

In any case, when designing a program for someone, the exercise is the last thing to consider, and the main components are always the clients goals and what they are ready for today to make them better for tomorrow. It’s not hard, but it does take thought and planning, plus enough leeway for adjustments as needed. Not every training session is in the optimal physiological readiness, so changing things on the fly is sometimes necessary. Plus, occasionally you may have to deal with some jack bag doing curls in the squat rack and not throwing your face through a wall.