How to Not Overwhelm a Strength Training Program

I can remember back when I was in university and taking an advanced program design course. The final project was putting together a 4 month program for a recreational rower who was also an accountant, trying to balance their workouts around income tax season and working 60-70 hours a week in some spurts. It was one of those instances where you had to look at every conceivable angle, figure out what would be the best way to periodize the workouts around their abilities and schedules, and hope that everything would go well.

After working on this program for 2 months, I was finally ready to present it and get feedback on how it looked. It followed all the rules set out through concepts like specificity, periodization, balanced physiological stress, and energy system training plus trying to reduce the stress of a unidirectional movement pattern like rowing by involving “unwinding” kinds of exercises, sort of like a golfer swinging a club the other way after a tournament.

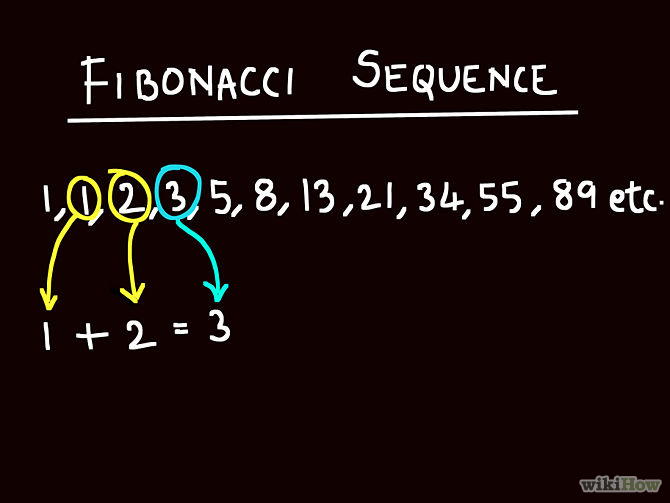

It was glorious. It was a Machiavellian work of art. The set and rep ranges looked like some sort of masterful Fibonacci sequence, and everything about it screamed excellence.

It would never work.

When I finished school and started working as a trainer in a commercial facility, I started to have to write programs for clients, and tried to replicate the same effect from my program design course with highly specific and complex programming so specific and finite that NASA would look at it and say “Damn, that’s a lot of attention to detail.” Some programs would take me upwards of 4-5 days to write, which was a quantum leap forward from the 2 months in program design class, but still unrealistic in terms of writing programs for multiple clients as needed.

Then I would give these programs to my clients. They were like looking at a vision of the “Coronation of Napoleon” and seeing all of the background stories involved, the artists renderings of the false reality and propaganda, and the secondary images that had been covered up and edited as needed. The downside to this is my clients were the equivalent of a Bermuda-shorts-wearing tourist at the Louvre just interested in seeing the Mona Lisa and getting a selfie with the statue of David. It was like Sheldon Cooper trying to explain string theory to Penny on the Big Bang Theory.

They didn’t get it, and as a result the program wasn’t working for them. It’s not that the workouts were bad, but when tasked to do them on their own, they didn’t understand things like “prone bent knee hip IR to ER w/ abdominal brace & cervical retraction,” like that’s hard to figure out at all. They would also do things like go to a work event the night before a training session and have a couple of adult beverages, then come in feeling less than stellar, completely screwing up my periodization. Occasionally they would have to cancel or reschedule a session, or didn’t show up, and that would just completely throw everything out the window.

What I learned from all this, and essentially what allowed me to continue working in fitness and not losing all of my clients or my mind, was the realization that the most perfect program would fall flat on its face in the real world where confounding variables are always competing for attention and resources. There was also the realization that the vast majority of people would benefit from focusing on becoming somewhat more skilled at the basics, such as doing a squat, lunge, hip hinge, push and pull. What it came right down to was hacking away at the unnecessary to find what was truly needed.

In time, my programs started to focus on less while trying to deliver more. I would include fewer exercises in total, but involve small variations on the common theme from one day to the next. Sure, 1 leg squats on a bosu while curling a dumbbell, pressing an elastic and singing “In a Gadda Da Vida” while involving eye tracking to stimulate cerebellular cortex action is awesome, and makes geeks like me want to wet themselves with excitement, but I would venture to say that teaching someone how to stand on one foot and not fall over while on solid ground would be easier for them to replicate on their own, and much easier to set up and progress or regress, and probably more beneficial in the long run to that client.

[embedplusvideo height=”367″ width=”600″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1v1kYzI” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/rfnQTHABk44?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=rfnQTHABk44&width=600&height=367&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep2660″ /]

Simplifying the exercise to involve fewer variables, fewer steps, and more concise and clear communication as to what should be done has had a tremendous impact on getting clients to know how to do the movements I’m looking for, and be able to replicate them on their own without much prompting or explanation. Doing this cut my program writing time down to more along the lines of 10-15 minutes per program, which is massive especially if you have more than 3 clients to work with. 30 clients and you’re desperate for any time-savings methods possible when it comes to programs.

The basics are necessary, and should have a lot of time spent working on them with less time spent working on more flashy or unnecessary elements. Basketball players always have to work on shot mechanics, ball handling, and body positioning on defence. Hockey players always have to work on skating, puck handling and positioning on defence. Golfers are always working on swing mechanics, which will dictate length off the tee more than absolute power, especially if they don’t want to slice it into the bushes.

A basic strength training program could have a couple different outlines, depending on what the goal is. Let’s say you have someone looking to lose bodyfat and gain some strength and they’re brand new to the gym. A very basic outline would look like this:

1. Squat

2. Push

3. Hip hinge

4. Pull

5. Lunge

6. Core Stabilization

So for the example of a beginner, let’s say they have no significant injuries or muscle imbalances, a simple variation of these exercises could be something like this:

1. Bodyweight squat or goblet squat with a dumbbell

2. Pushups off a bench or floor

3. Deadlift, either with a kettlebell to learn the movement or with a barbell if they can tolerate it.

4. Hanging pullup off a smith machine or TRX, or chin ups

5. Stepback lunge, hands either by the sides or behind the head in a prisoner position.

6. front plank or farmer walk with two dumbbells.

You could do a straight circuit of these exercises or pair them up in twos or threes, and even run through them twice with a different set of variables attached to make them somewhat different yet similar.

This is a simple outline that can be given to almost anyone and get them results. The specifics of weight used, speed, sets and reps, position of weight and other fun things like that can be adjusted to the individuals tolerances and what they’re working towards, but the schema can remain relatively the same. This stupid-simple process makes it easier to write out programs, give to clients, have them understand, and do as needed either on their own or with minimal guidance.

A simple, repeatable and scalable program template can make a massive difference in a trainers life, and having similar systematized aspects of life can help non-trainers get through their daily struggles a lot easier, plus leave more room for putting energy towards max weight squatting, which is ALWAYS a good thing.

Keeping to this concept, you should check out Mike Robertson and Joe Kenn’s new video workshop Elite Athlete Development Seminar. It’s a 15 hour video series, and they’ve also included a live Q & A session for anyone who buys the series by tomorrow at midnight est, and also now have 1.4 NSCA continuing education credits.

Mike simplifies things with his R7 approach, and Joe outlines the finer points of the Tier System, the combination of both methods will essentially show you the guts of every program you would ever need to write or go through on your own.

Mike simplifies things with his R7 approach, and Joe outlines the finer points of the Tier System, the combination of both methods will essentially show you the guts of every program you would ever need to write or go through on your own.

You can save $150 on the entire package if you order by midnight Friday evening, August 22nd, so get on that now.

===> Get EASD NOW!!! <===

If you don’t get their series, at least try to keep your programs as simple as possible, but no simpler. You could always spend some time working on the basics and compound movements, regardless of what you’re training for. You can never be too good at the fundamentals.

3 Responses to How to Not Overwhelm a Strength Training Program