How to Develop Killer Speed

First, this is not an article about a run-away bus with Keanu Reeves trying to save the day. It’s about making you rediculously, time-bendingly, brain-meltingly fast. I have a lot of endurance athletes and wanna-be endurance athletes training with me right now, trying to get faster after trying it on their own and not getting anywhere. When they begin training with me, I follow a pretty simple yet completely different route than many coaches or trainers take: I make them run fast, then I make them run faster, then I shorten the distance and make them run faster, then I lengthen the distance and make them run faster still. Want to know the secret? Here it is.

The basic formula for speed is as follows:

Speed = stride frequency x Stride length

Having a long stride can sometimes make up for a slower stride frequency, but this is more

Take a look at Usain Bolt running, but forget about the German announcer.

He covered the distance in 33 steps, which is an average of 3 metres per stride and a rate 207 strides per minute. Consider his next closest opponent, Tyson Gay, who ran a personal best in this race, did it in 42 strides, averaging 2.38 metres per stride and a stride rate of 261 strides per minute. Who won? The guy who got to the line first, WHO DO YOU THINK???

Comparing this to endurance runners or your average distance runner, and their stride frequency drops to between 150-160 strides per minute, and a stride length of anywhere from 0.75 metres to 1.2 metres. When I’ve done video analysis on run clients, I’ve seen that beginners tend to increase their stride length more with increases in velocity and maintain a fairly consistent stride frequency, whereas more elite and trained runners will increase their stride frequency first, then increase their stride length.

Now that we’ve talked about the basic science, let’s look at muscle action. We all know triple-extension of the ankle, knee and hip propels the body through space on our way to a personal best and amazing glutes.

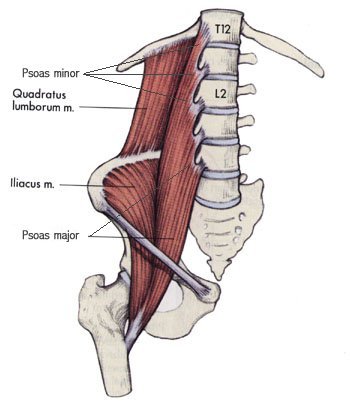

However, that only works for the stride length. If we want to work on increasing the stride frequency and we’re only focusing on how much power we put into the ground on every stride, we’re forgetting the point that getting the leg back into position to strike the ground again is just as important and being able to push the ground in the first place. The swing or recovery phase of the run stride involves bringing the foot back into the front of the body by way of the hip flexors and abdominal muscles. In order for the hip flexors to do this properly, the spine has to be solid to act as an anchor for the psoas to pull against it to create the maximal amount of torque. If the spine is unstable, the psoas will either not recruit enough strength, or it will pull the spine into injury, either way it impairs performance.

When the hip goes into extension, like pushing yourself forward in a run stride, the hip flexors become stretched much like an elastic. The springier the elastic, the greater the ability of the hip flexor to explode from full extension back into hip flexion where it can reload and prepare for the next strike. Not only that, but it helps to carve out that amazing “V” shape at the bottom of the abs. You know what they say, the arrow points to the treasure!! Yeah!!!

Take a look at an amateur runner and look at his stride length. Look at how the leg recovers in the stride and how it doesn’t really spring into flexion.

Most of your basic runners will have a run form like this. Quite honestly, it makes me laugh. They run and run and run and never get anywhere!!! Now take a look at an elite runner and how their leg is almost thrown from the back of the stride into flexion.

See how they almost kick their own butts, bringing their heels really close to shorten that lever arm length, which allows them to bring their hips forward easier and faster, while simultaneously driving their knees forward to create that elastic recoil from one leg to another.

In order to train this ability, doing squats, deadlifts, power cleans, and what have you will be useless, as the movement is a triple flexion movement, not triple extension. Don’t get me wrong, I have a bit of a creepy fascination triple extension, and think it should be used in any run program, but we should also work on the opposing directions as well, making sure there’s sufficient work to increase the speed and strength of contraction of the hip flexors bringing the knee forward to prepare for the next strike. Increasing extension power can increase stride length, whereas increasing flexion power and speed can increase stride frequency. We could therefore rewrite that original equation like this:

Speed = Triple flexion acceleration x triple extension acceleration

If you’re running, try to increase your stride frequency, and work on bringing your heels closer to your but when you have the full extension, that way you can have a faster recovery and be able to hit the ground sooner, which will propel you along faster.

If you’re in the gym, try to avoid slow hip flexion activities in favor of fast ballistic movements that increase contraction velocity. Definitely make sure you have a tightly contracted core before doing this, pretend like someone is coming to punch you in the stomach and your gonna flex hard, hoping to break their hand, or at least make them fear for their lives that they dared touch your abs. By contracting the core, you can increase spinal stability and prevent the psoas from pulling on the lumbar spine and causing some damage. Tuck jumps are a great example of a coupled exercise that pairs triple extension with triple flexion in one movement.

One Response to How to Develop Killer Speed