Recovery and Adaptation: The Missing Piece to Most Training Programs

Today’s post is from Eric Bach, a strength coach from the Denver, Colorado area. The ideas presented about recovery are very important to consider for everyone, not just athletes, but also to those A-type folks who think the laws of training don’t seem to apply to them and the only way to train is full blown all the time. I’ll let him take it the rest of the way from here.

Yea, we’ve all been there. Two dudes in cut-off smedium t-shirts screaming while a third quivers under an overloaded barbell. “Awesome Bro!” is yelled across the gym while confused on-lookers shake their heads and chuckle. [Note from Dean: I prefer my shirt size as extra-medium, as smedium is slightly too tight for this guy. There’s a point I won’t cross.]

While improper form and the “broisms” are the brunt of jokes, they do have something right—effort. Rather than gliding along on the recumbent bike, or trying to stand on a stability ball, they’re pushing their bodies beyond homeostasis. Stimulation is the first step to improving performance and building a strong, shredded, and athletic body.

The next phase is equally vital: recovery. Training creates a stressful response to the body that over-time, can to become too great to recover from. Without emphasizing recovery training adaptations can’t take place. Here’s how to maximize your gym efforts.

Adaptation: How It Works

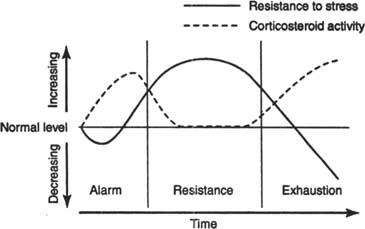

The manner in which we respond to stress is best described by Hans Selye with the General Adaption Syndrome (GAS).

GAS states that the body goes through a specific set of responses (short term) and adaptations (longer term) after being exposed by an external stressor. The theory holds that the body goes through three stages, two that contribute to survival and a third that involves a failure to adapt to the stressor resulting in DEATH.

Okay, you won’t die, but you’ll reach a state of overtraining.

The goal of training is keep the body adapting to new stimulus and recovering while avoiding the exhaustion phase with proper programming and deload periods.

According to Practical Programming for Strength Training by Mark Rippetoe and Lon Kilgore, here are the stages of GAS and their relation to training:

Stage 1: Alarm or shock. Alarm or shock is the immediate response to stress and can include feeling flat, soreness, and stiffness. A slight reduction in performance occurs at this phase. The more advanced the athlete, the greater the stress needed to induce the shock phase.

Stage 2: Adaptation or resistance. Adaptation occurs as the body responds to the training and attempts to equip itself with the tools to survive exposures to stress. In training this can include hormonal adaptations, nervous system adaptations, and tissue building. Adaptation is unique to each individual and varies due to training age and work tolerance in proximity to the genetic ceiling. A gym newbie may recover from this quickly – within 24 hours – while an advanced trainee may require months to disrupt homeostasis and adapt to higher training levels.

Stage 3: Exhaustion. Simply put, is overtraining. This occurs when the stimulus is too great for the body to adapt. This is most applicable to moderate-to-advanced athletes, and signals that excessive high magnitude, frequency, and duration exercise should be avoided.

In training the goal is to maximize adaptation, while avoiding exhausting. When recovery is maximized in the resistance phase neurological, muscular, and mechanical changes lead to increased performance in the process of super compensation. This is the ultimate goal. (Baechle & Earle, 2008)

Simply put, gains are maximized when stress from training disrupts homeostasis, but doesn’t overwhelm the body. Once sufficient stress is applied, recovery comes in to drive progress forward.

The Role of Recovery

Training hard is rarely the missing piece for progress. That title goes to recovery, the vital component that most athletes neglect. Intense exercise causes tons of stress: joint & ligament stress, muscular damage, neural fatigue, and hormone disruption are all factors that must be taken into account and is highly individualized to each athlete. Beginners may be able to go for months without backing down; however, advancing athletes require individually specialized programs to maximize training gains.

How to we Maximize recovery?

Proper periodization and implementation of the deload: a time period of training with lower volume, intensity, or both to enhance recovery and the subsequent training response.

Properly planned deload weeks provide the rest and recovery to aid in the recovery of joint & ligaments, muscles, the mind, the nervous system, and re-optimize hormone ratios. Deloading promotes healing of stressed tissues to optimize adaptation and prepares the athlete to continue training at a skin-splitting intensity.

How to Deload

Deload weeks are simple–just back things off to a lower intensity every few weeks of training. I recommend the three-on-one-off and five-on-one-off cycles for athletes. Work out on consistent days to maintain a schedule during deloading, as this maintains focus and discipline. Schedule your deload weeks in advance and have a plan of action. Focus on your important movement patterns combined with engaging low-intensity activities to provide a mental and physical break from training.

Deloading requirements depend numerous factors: training age, sport, training goal, frequency and intensity of the workout, and season of sport. There is an inverse relationship between intensity (1RM) and the number of reps per set. For this reason, varying intensity and volume through workouts is best for recovery and max effort training. Below is sample four week micro-cycle a deload week during the forth week.

Volumes and intensities listed are for a compound exercise such as a deadlift or bench press for a moderate athlete training to improve maximum strength.

Week 1: High Intensity/Low-Moderate Volume, 4×3, 85-92.5% 1RM

- Week 2: Moderate Intensity/Moderate-High Volume, 5×5, 75-85% 1RM

- Week 3: Very High Intensity/Low Volume, 4×3, then 2,2,1,

- 85-100% 1RM

- Week 4: Low Intensity/Low-Moderate Volume, 3×5, 50-60% 1RM

**Other activities including high-intensity movement sessions such as speed, plyometrics, and agility work must be taken into account and should be performed in a non-fatigued state due to their large neural requirements. This could fatigue the athlete and require greater downtime before moving to strength training or using less intense training loads.

Using the same training intensities weeks one and two and three and four can be switched, improving recovery before the very-high intensity week. This works better with more advanced athletes.

- Week 1: Moderate Intensity/Moderate-High Volume, 5×5, 75-85% 1RM

- Week 2: High Intensity/Low-Moderate Volume, 4×3, 85-92.5% 1RM

- Week 3: Low Intensity/Low-Moderate Volume, 3×5, 50-60% 1RM

- Week 4: Very High Intensity/Low Volume, 4×3, then 2,2,1, 85-100% 1RM

On deload weeks, training similar movement patterns is imperative to preserving the neuromuscular pathways of training without breaking down the body. This can be as simple as changing bar position on a back squat, moving from a power clean to a hang clean, or performing pulls from blocks instead of the ground. This works well for maintaining form and speed work to preserve form and muscle mass. Cool, eh?

Considerations

Rather than complete rest it’s important to focus on active recovery. During a seven-day deload, aim for three or four complete rest days and three or four active recovery session.

Active recovery workouts should include: Submaximal technique work (<65%), low intensity activity performed to improve recovery, mobility and flexibility training, and some soft tissue work.

Listen to the body. If you feel stale after the warm up and main lift, it’s fine to pack it in, hit some light active recovery, and end the session.

Nutrition

Leave the Crunch-Wrap Supreme and Baconators along. A deload on training intensity isn’t permission to slack of on your diet. Doing so will provide you with a spare tire filled with shame and gluttony. A lower training stimulus provides additional recovery resources to the body — choose your diet wisely.

Remember, it’s repair time.

It’s essential to provide the body with fuel to complete the repair. Recovery is not just the absence of training. Recovery is the combination of rest, nutrition, and care for your body.

Wrap Up

Elite status in any athletic endeavor requires long-term training. Proper recovery is the key to long-term training and improved performance. A focus on recovery will decrease incidence of injury, increased athletic performance, and increase motivation for subsequent training. After a deload your body is primed and ready achieve higher levels of performance –Take advantage of the opportunity.

In Pursuit of Strong, Shredded, Athletic,

Eric

Eric Bach, BS- Kinesiology, CSCS, and PN1 is a sought after trainer in Denver, Colorado. Eric coaches at the renowned Steadman Hawkins Sports Performance and runs Bach Performance, an online coaching community and blog. Eric works relentless to fine tune the best methods helping clients get strong, shredded, and athletic. Please contact Eric at http://bachperformance.com, Facebook or Twitter for all inquiries and consultations.

- Rippetoe, Mark, and Lon Kilgore. Practical Programming for Strength Training. Wichita Falls TX : The Aasgaard Company; 2nd edition , 2009.

- Baechle, Thomas, and Roger Earle. Essentials of Strength and Conditioning. 3rd. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics , 2008. 382-384. Print.