Do You Really Need an MRI?

I get a lot of emails, Facebook messages, and even the random text message from people hoping I can somehow diagnose their shoulder, knee, back, or even the odd leaky bladder issue from across teh interwebz. While I normally can get a good idea if someone gives me all the pertinent info, the answer always comes back to “get it diagnosed by someone who can see and test you in person, and preferably someone who is a doctor, physical therapist, chiropractor, or voodoo shaman.”

I’m flattered that people think I can help them out through digital communication mediums, but getting the odd message like this is always a little strange and perplexing:

Hey Dean! My knee hurts. What kind of squats should I do to fix it?

People wonder why doctors retort to stuff like this by saying “keep off it,” but when you give so little information, you’ll get a very vague and general answer, Bubba.

Even more perplexing is when people ask if they should get an MRI on their injury to see what’s going on. First, I can’t prescribe them. That’s up to a doctor. Second, even if you get the MRI done, what will it tell you, and what will you do with that information?

Let’s say you’re one of the estimated 80% of North Americans who develop low back pain. You pop a few pain killers, struggle through your days, and can’t get relief in any position you try. You bite the bullet and decide to go to the doctor to see what’s going on. The doc will then go through a differential diagnosis to try to see if there’s some immediate need to take care of, like heart disease, tumours, or something that will actually kill you. Once they’ve cleared those, they know you’re not going to die, so the immediate need to send you for imaging to confirm or refute the possibilities of a structural issue aren’t there, so they’re going to go through some manual orthopedic testing, which cost the medical system considerably less than having you or your health care provider pony up a grand to pay for a scan as well as the technician running the machine, and the radiologist reading the scan.

If they’ve gone through an assessment and determined whether a scan is necessary due to some red flags in your testing (bone pain, provocation testing that’s showing signs of some structural issue like discs, etc), they may send you for a scan to confirm whether or not you have a disc issue or something like that which could cause paralysis or need surgery to correct.

In most cases, this isn’t necessary, so they’ll refer you to a physical therapist or in some cases to a guy like me to help you get stronger and show you ways to move and manage the symptoms while healing as best as possible. Most disc issues do tend to self modulate, but they suck the life out of you while they do. It could take 6 months or more to heal, and in the mean time you feel like a bowl of hot buttered fail.

Let’s say you’re not satisfied with this course of action and decide to get the MRI on your own. The scan comes back and shows a small bulge at L3-4 and L4-5. Nothing too crazy, no indication for surgery, nada. You’re in the same boat as if you hadn’t gotten the scan (going through physio and not a surgical candidate) but now you have $1000 less to play with.

A paper published in 1998 by Weishaupt et al showed that disc bulges occur in about 42% of the asymptomatic population. A study by Hollingsworth et al showed that patients in pain had no consistent scans related to disc herniations and cause of pain, and those who had neural compression actually reported BETTER quality of life than those who didn’t. In their own words, “There was little relation between the extent of disc abnormality and quality of life.”

A study published this year by Willems showed that the prognostic benefits of an MRI prior to spinal fusion surgery didn’t necessarily predict a successful outcome based on reduction of pain and improvement of symptoms or quality of life. A study by Mainka et al showed that facet joint swelling was present in 86% of patients with low back pain, but still 75% of those without back pain. They found that only the combination of provocation testing AND positive findings of joint effusion on scans correlated to low back pain. The scan on its own wasn’t good enough to pick up the issue.

A study from the University of Alberta and University of Calgary showed that low back MRIs were considered inappropriate in 50% of patients, due to a lack of findings that would indicate the need for the scan in the first place. This means that while they can rule out things like fractures, disc issues, and tumours, there’s probably a better method to do this, like a manual or orthopedic assessment by a qualified practitioner.

What all this means is the typical MRI will only tell you about the structure in question, and doesn’t have a lot of consistency in dictating whether that structure is the source of the pain or secondary to it. You could have the cleanest MRI in history and have crippling pain, or a scan that looks like a walking train wreck, and have just finished a max deadlift PR that morning without any issue.

In other words, they only tell you what they see, not why you may have pain, especially if it’s not directly related to structural issues.

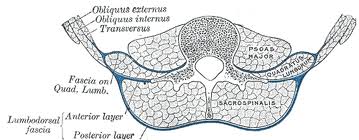

One type of MRI that does have a higher correlation in low back pain is looking through a transverse section and checking the relative symmetry of the paraspinals. When one side is dramatically thicker and more well developed than the other, there’s a higher correlation to a potential link to low back pain.

A study by Battie et al showed the segment-specific multifidus muscles around a disc herniation had a significantly smaller cross sectional area compared to the unaffected levels above and below the herniations, and that there was a stronger correlation to low back pain and asymmetrical cross sectional area compared to asymptomatic controls.

So what does all this mean? Should you get an MRI?

I always ask people a simple question: If you get the MRI done and it comes back showing you have a disc issue, you’re like a lot of other people who have no pain. Would you get a surgery to fix it, knowing you would have to go through the same rehab afterwards and probably have the same chances of not having pain than if you hadn’t had the surgery?

If the answer is no, then there’s no need to get one. However, let’s say you’re getting a loss of function, numbness and tingling through your legs, and you can’t sleep at night. It may be worth talking to your doctor to see if a scan would be at all beneficial to qualify you for surgery or not, and in most cases unless you’re admitted to the ER, you’ll have to wait a few months to get an appointment.

What about for a knee issue? To be blunt, if you can walk, squat and lunge on your knee, the odds of something needing the diagnostics of an MRI are pretty low. If you can’t walk, weight bear, or if you notice it’s swollen to twice its normal size, it could be recommended, but an X-ray would be a simpler bet unless it’s an ACL tear or meniscus tear. Even then, some MRI’s don’t pick them up, and they need arthroscopic surgery to diagnose and treat effectively.

What about the shoulder? Sure, an MRI can tell you if you have a tear to your supraspinatus tendon, but Sher et al found 34% of asymptomatic folks had tears to their rotator cuffs, and that number jumped to 54% when they were over 60, which means you’re like the other guys who have tears, but they aren’t complaining about it or needing surgery. If you’re planning on playing baseball, you might want to get a surgical repair to keep your shoulder from exploding every time you throw the ball, but if you mine the office cubicle farms, you may not benefit from it that much.

Let’s cut to the long and dirty of the discussion:

- most people don’t need an MRI, because most of the findings aren’t indicative of what the major problem actually is, nor is it confirmed with a high degree in some cases.

- MRIs can’t tell you where postural strain or inflammation (beyond joint or tissue effusion) lie, which means most chronic injuries or repetitive strain issues aren’t detectable.

- They CAN tell you if you have a fracture, break, rupture, or some other structural issue, but then the course of treatment may not be any different versus not knowing

- If you lose function through an area, talk to a doctor, not a trainer over the internet, and hopefully give them more symptoms than “it hurts.”

- Pain is more than structure and biomechanics. Matthew Danzinger wrote a great guest post HERE detailing some of the more prevalent info about it. In many cases, MRIs can’t touch the source of pain, nor can they tell you anything about how to fix it.

- Surgical procedures have their own risks and recovery timelines, so if you want to go that road, be prepared for the rehab, as well as the chance that it may not fix the problem in the first place.

MRIs have helped save the lives, quality of life, and overall function of a lot of people, and are probably one of the most significant advances in medical science of the past century, but with as great as they are, they are only limited in their ability to assist. They are a tool for the medical professional to use, and in most cases aren’t going to be helpful, or will be minimally helpful to simply confirm a suspicion and make some recommendations based on what’s seen. Do you need one? For most people, I would say no, unless you had a traumatic injury, lost function, have trouble doing activities you enjoy, or have gone through an orthopedic assessment and had some red flags come up that warranted further testing.

Talk to your doctor, physical therapist or chiropractor and see if they would recommend one. Then, get a second opinion from a different practitioner, and if they both say the same thing, follow their directions.

Was I in line or completely off base? Drop a comment below and let me know what you think.

25 Responses to Do You Really Need an MRI?