When Training Can't Help

Every now and then I wind up meeting with someone who I literally shouldn’t be working with. I had a consult like that a few weeks ago, the person had severe knee pain, swelling, and limited passive range of motion. She had a noticable limp and was taking a lot of OTC pain medication to get through the day. Her friend had trained with me and seen some great results following an ACL reconstruction, so she wanted to meet with me to see what I could do.

I gave her the card of a physiotherapist I trusted and said to go work with her until she gave clearance to come back and begin training.

That’s really all I could do for her. She was in pain, and upon a basic assessment I couldn’t get passive range of motion without pain, so there would be no way I would risk trying to do any active stuff with her and cause serious damage. She wasn’t ready, and I wasn’t about to try to push water up hill.

Let’s face it, as much as I like to pretend I know everything on this website, even if I’m completely joking and overstating the obviousness of me NOT knowing everything, I’m pretty good at knowing my limitations and not over-stepping them. The last thing I want to do is hurt someone, as I know how much being in pain sucks. It’s no different than someone who is a plumber trying to say they can be an electrician. I like to take people who are ready to train and turn them into absolute beasts who want to deadlift copious weights and give fist pumps and high fives all over the place while crushing protein shakes and eating the equivalent of a cow each and every day.

For the most part, I never work with someone who is in direct pain and who has limited function in and around the area of their pain. For example, if someone has shoulder pain and they can’t raise their arm overhead, they get an immediate referral out. If someone can raise their arm overhead, I’ll try to map out which movements they have full ability, partial ability, or some form of pain and typically refer them out to get a second opinion, sending my assessment results along with them. We’ll probably begin working together quickly once they get a clinical assessment and plan of action, but I always want to be sure.

Having physiotherapists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and physicians I can send people to who I’ve worked with and trust the quality of their work makes my job as a trainer a lot easier. A second set of eyes with different training and experience can help me see things differently, and help make me a better trainer as a result.

Sometimes a referral isn’t going to give me any additional information. This comes up when someone has either moderate or severe degeneration in a joint that doesn’t present with isolated movement patterns producing pain. Sure, I’ll still get them to go to a physio or a chiro just to make sure, but most of the pain is coming from the degeneration and altered structure of the joint, something that may not be correctable through exercise or conventional treatments.

Even though this is something I can still work with, I always have to go into it knowing that any progress we can make is going to be minimal or more of a “improving what can be improved” basis than hoping for a cure.

I’ll give you an example. I have a client with a severely degenerated left knee whom I’ve been training for the past 6 years. In that time he’s made some great progress in strength, balance, stability, and overall functional capacity. The downside is that his knee has not improved, and has actually regressed over time.

He was kind enough to allow me to share some of his information to illustrate this point. Take this video of him walking on a treadmill last April:

Notice the pivot shift in his left knee when walking.

Now here’s a video I shot over our last session this weekend:

The knee is snapping out a lot further than before, and the tibia is rotating to a greater extent than in the previous year.

He recently had an appointment with an orthopaedic surgeon regarding getting a knee replacement in the future, which is pretty much the only way he is going to get any substantial relief. There aren’t any exercises, stretches, or soft tissue work that will correct that problem.

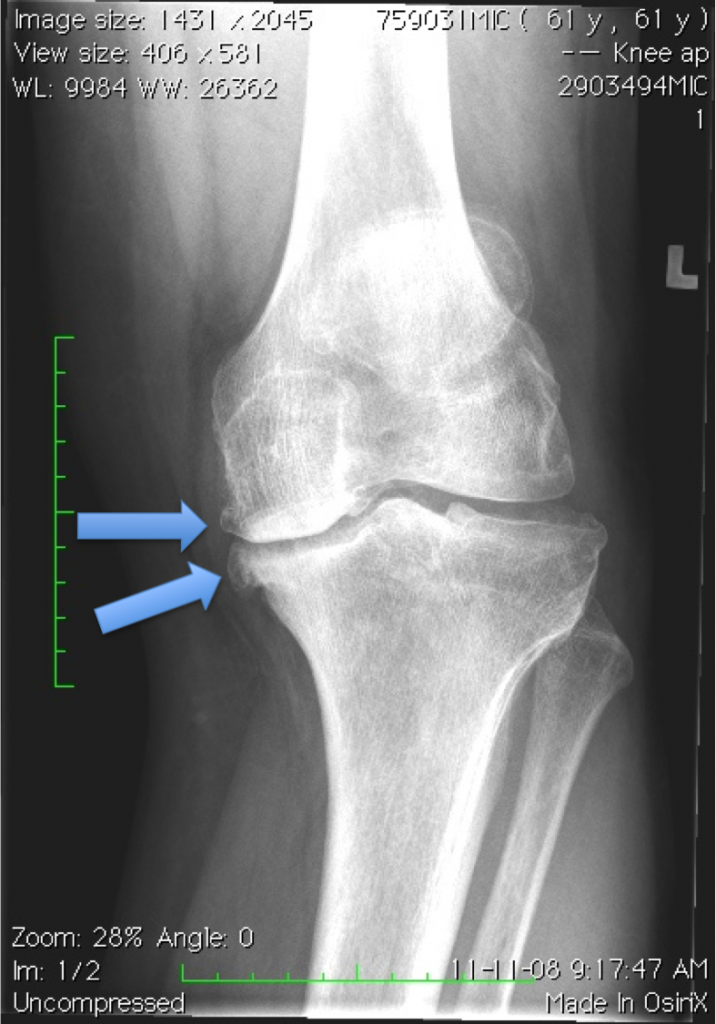

To reinforce this fact, check out the X-ray of his left knee.

The arrows are pointing to osteophytes developing on the medial aspect of the femur and tibia. Also note how the medial meniscus has completely collapsed and he’s almost rubbing bone on bone. The lateral meniscus has compressed as well.

We can’t stretch this out, bro.

Most training program design courses teach based on the assumption of a normal structural anatomy, assuming that the only alterations that need to occur are through the musculotendinous and cardiopulmonary systems. The simple fact that probably 99% of everyone over the age of forty has some structural abnormalities and degeneration that creates a physical limitation or potential risk factor to exercise means that most of these courses aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on.

Occasionally we’re going to get someone who is in a situation that can’t be fixed with an exercise program, and will need more intensive treatments and potentially even surgery. As much as I believe we have a knee-jerk reaction as a population to believing that surgery is required for everything and that there are a lot of unnecessary surgeries that don’t fix the problem, there are still a lot of situations, like Fred here, where it is definitely warranted.

I had a client who had gone through three surgical repairs to the cartilage underneath their knee cap to reduce her pain and help her continue running, but the bigger issue was her glutes weren’t firing and she was running with a hard heel strike with a flexed hip on contact. Altering her run technique and getting her glutes going helped to keep her out of surgery for a fourth time and kept her out of an 8 week rehab stint following the procedure. A surgeon wouldn’t pick up on that because they don’t look at the movement capacity of the individual, much as I don’t look at the type of wires used to fixate an ACL graft or the thickness of the annulus remaining following a disc herniation repair.

I’ve worked with a few dozen clients who were in preparation to get a knee replacement as well as following their surgery, and the difference is dramatic. Immediate pain relief, increased strength and increased range of motion means they can now climb stairs, walk, and do almost everything they want to do once again.

Fred will be fine once he gets his knee replaced, and we’ll be able to make some serious headway in his health and fitness once he can manage pain-free activity once again. Until then he’s working on maintaining what he has, soft tissue work to reduce pain and stiffness of the supporting muscles, and keeping a positive mindset.

The whole point to this post was to show that trainers aren’t always going to have all the answers, and we have to understand what our limitations may be. We can do a lot to making someone stronger, more flexible, lose weight and get some better cardio, which has a huge benefit across the board for their health and recovery, plus giving them enough confidence to feel like they’re the reincarnation of the Incredible Hulk, but as with any profession, we work best when we allow ourselves to be fallable.

6 Responses to When Training Can't Help