The Exercise Itself Isn’t Important

Let’s say you want to get stronger in your lower half. You start banging out squats, front squats, deadlifts, pistol squats and every manner of leg exercise imaginable. You train heavy and hard, and see your number start to creep up towards a somewhat respectable number. Then someone with a keen eye for technical expertise like me walks by and says something along the lines of “Dude, stop doing that, my eyes are bleeding just watching that atrocious display.”

Up until that point, you had no idea anything was wrong. I mean, you show up, grab the bar and heave that shiz-nit all over the place. Isn’t that what you’re supposed to do? Now I love training heavy just as much as anyone, but when you’re moving ungodly amounts of weight, it becomes even more apparent that optimal technical execution is required in order to not only prevent injury, but to get the absolute most efficient use of your muscles so you don’t make your deadlifts look like a bent over row or have your squats look like Patrick Roy throwing down some butterfly in goal.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common limiting factors in some of the popular lifts, and see if there’s a way you can develop a killer instinct without making everyone laugh at you in the gym.

Hips: The Power Center

It’s not uncommon for someone to be able to back squat their body weight or more but not be able to do a proper glute hip bridge without over-recruiting their hamstrings or lower back, or perform a forward bend to touch their toes without first hinging at their lumbar spine instead of from the hips. We see this on deadlifts as well, as evident by Chotchy shown earlier throwing down some of the best lumbar extensor isolated deadlifts I’ve ever seen (sarcasm is awesome, isn’t it??). Standing on one foot is another way to tell if the hips aren’t doing their job, as the person will hike up over the stance leg instead of standing tall and strong, or flail around like thy’re doing some type of interpretive dance to unheard music

To be honest, when I see anyone come in for training, I’ll take them through a movement analysis and I’m typically not surprised to find a lot of people have no hip strength or single leg stability whatsoever. So then when I ask someone to show me a deadlift, even if they’ve been lifting for years, I wind up correcting pretty much every aspect of their setup and pull, beginning with getting them moving through their hips and figuring out how to stand without rocking up to their toes or falling back on their heels. Even a basic overhead squat can become a real issue without weight.

If the hips are weak or unstable, they will rob from another part of the body to get the requisite mobility or stability needed to get through the movement in the most efficient and pain-free manner possible, while masking the lack of functionality. This is why knee issues and low back issues can crop up from weakness in the hips. The knee has to bear more weight and the spine has to create more of the motion, leading to breakdown through repetitive overuse.

Since the tendency is to move away from the hips as much as possible when doing anything, a corrective exercise has to be done specifically and technically perfect to not allow any cheating to occur. Otherwise it’s not correcting anything, and it’s only going to re-enforce the problem by grooving a new dysfunctional pattern. Simply performing the exercise is meaningless without technical precision.

For any corrective exercise to work, it has to correct something, and keep it corrected. You could say that any exercise is in essence corrective by nature, which means the best form of corrective exercise is to put the person in the goal movement and make sure they do it perfectly. This means helping them get the right pelvic tilt, centration over or under the weight, foot placement, spinal alignment, head position, shoulder position, and breathing patterns. If you’re getting all of this down, the movement itself will correct a lot of the problems being shown.

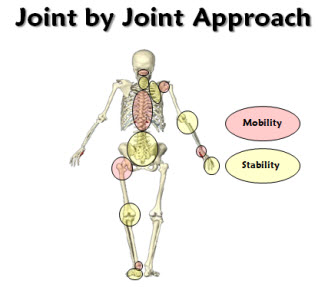

One way to tell if the person needs a corrective exercise or not is to simply compare their passive mobility to their active mobility. If they can go through a full range of motion without any load on their body, but lock up when you have them do any active movements, they have a stability issue and should have stability exercises. If their range of motion is restricted without any loading on them, they would probably benefit from some mobility work. At that point it would be best to use something like the Joint by Joint approach, popularized by Gray Cook and Mike Boyle as a way of determining which areas of the body need more mobility and which need more stability.

To get more info on this approach, check out Gray Cook’s book Movement, or Mike Boyle’s book Advances in Functional Training.

To give you an example of how a lack of mobility in one area can create issues in another, I had a student shadowing me earlier this week, and during a short break he asked if I could look at his shoulder. I had him go through an overhead squat and found he had collapsed arches, knee valgus deviation, lumbar flexion, anterior head position and internally rotated shoulders. I did some corrective work with his hips to help him get deeper into his squat, which involved getting him to learn how to grip the floor with his feet, straighten up his back, and get his neck to stop turtling forward, and after about 5 reps of squats (with no arm involvement whatsoever) he said his shoulder hurt a lot less and his range of motion was noticeably better. Fixing the hips (or at least improving their functional ability) made sure that other areas weren’t compensating, and essentially took off the e-brake that was holding them back.

Some people won’t have the right mechanics to squat or deadlift effectively, which means you need to have someone in your back pocket to help you out when it comes to people who have pain or really screwed up patterns. Every trainer should have a network of health professionals that can help with soft tissue work, diagnosis, and therapeutic treatments as needed. Occasionally, if someone comes in with severe osteoarthritis, squats are the very last thing I’ll get them doing, as their structural mechanics aren’t optimal and performing any movement where they push into pain will cause more degradation than benefit.

Thoracic Spine: The Director

If the his are the driver of performance, the thoracic spine is what tells the body where to aim that power. If you didn’t read my 3-part series on the thoracic spine from last week, check out Part1, Part 2 and Part 3. I guarantee it will make your mind explode with sheer awesomeness, or your money back.

The thoracic spine has the ability to produce almost 4 times the rotation as the lumbar spine, but only if the spine is placed in either a neutral or slightly extended position. If the spine is flexed outside of neutral, the rotational capacity drops to about half of normal, and in order to pick up this additional rotation it steals it from the lumbar and cervical spine, meaning a lot of head and neck issues will also come from the thoracic spine. On top of that, if the t-spine is flexed and you’re asked to go through extension, the main area that gets the job done is the junction between the thoracic spine and the lumbar spine, which tends to result in a lot of shear force and probably some damage to this site. You can see this in a lot of poor overhead press movements.

One thing that’s always kind of made me laugh is if someone has a lack of thoracic extension, and you give them a cue to raise their chest, they wind up extending their neck and looking up and keeping the chest in the exact same spot.

Performing a movement like a deadlift or a squat, and even something like a bench press or even a pullup requires a good degree of thoracic extension. This allows the scapula to glide and rotate to shorten the length of the lever arm along the spine and increases the co-contraction of spinal muscles and lats to make the spine a locked and solid piece of twisted steel that won’t have any kind of of shear forces or deformation going on. It’s the essence of the phrase “spinal stability,” the ability of the spine to resist deformation in the presence of changing forces.

If you sit with a chronically flexed T-spine, you’ll probably fall into the trap of doing self-myofascial release to areas like the pec minor, rhomboids, neck, lower thoracic extensors, yadda yadda yadda, and when I tell you to stand up tall you wind up looking like someone ready to ring the bells and yell “De plane boss!! De plane!!” Sure, SMR work is important, but it’s not something that MUST be done all the time and with little change from one session to the next. If you’re improving your posture and muscle balance, you should be able to do less and have more strength, power and stability due to the muscles not holding tension for extended periods of time, and they’ll actually be able to let go once in a while.

I know I’ve talked about the benefits of SMR work in the past and how it’s really important, and it is, but it’s something that is similar to a chiropractic adjustment: it unlocks areas of the body that can restrict movement, and then the movements should be trained to reinforce the new length and tension to prevent the return to abnormal. It has its’ role, but it’s not the end-all be-all cure to everything.

Let’s look at something like a plank. Ideally your spine should be in relatively the same position when horizontal as when vertical, with small alterations to adjust to the variance in gravitational loading from axial to transverse. If your idea of a plank is to resemble a camel with a massive thoracic hump, you’re doing it wrong. If your lumbar spine dips lower than Christina Milian (remember her?? Me neither), you’re doing it wrong.

Posture becomes everything, and positioning becomes the root of what makes a corrective exercise something that can actually correct a dysfunction. Simply going through the motions does less to fix the problem than slapping a saw against a board does to cut it.

Rest periods should be as much for the trainer as they are for the client, as you should be so involved in the technical precision that you feel like you got hit by a truck and are mentally exhausted, and you need another 60-90 seconds before you start working with them on the next set so you can make sure they aren’t slacking off and screwing up their hard work. It’s one of the reasons not a lot of trainers will focus on corrective exercises, and one reason why the ones who do can charge a lot more than other trainers (Hint to trainers: if you want to make more money, re-read this post a few dozen times).

As another example, I have a client who has been dealing with a sore neck for years. She has an anterior head position, shrugs her shoulders to make her neck disappear (the no-neck look won’t be hot this spring, just sayin), and had a posterior tilt to her pelvis. After getting her to straighten up and work on simple postural exercises, her shoulder were hanging lower, her but was actually showing, her jaw looked like she wasn’t trying to bite through steel, and amazingly her neck pain had almost completely vanished.

It wasn’t exercises per se, but more working on positioning and bringing an awareness to her of what should be working and what shouldn’t be working. The next time she came in, we worked on similar things for about 5 minutes and she was good to go. We then went and lifted ridiculously heavy things and she’s never looked back (even though now she can because she can rotate her head without pain).