The Best exercises You Could Ever Do: Quad Activation Progressions

It seems to be that time of year again, where everyone and their dog is getting a knee injury or something that is causing knee pain (seriously, one client’s dog had to have ACL reconstruction surgery, so it’s not even just a saying. The little guy is doing fine now, thanks for asking). Now I would love to go on a rant about how most of the knee problems in the history of the world are due to piss-poor mechanics and technical faults (insert point about the Portland Trailbazers S&C coach needing to be bludgeoned with his own foam rollers), but unfortunately, just as many are from freak accidents, slips and falls.

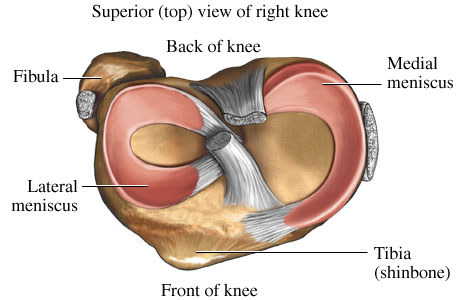

Regardless of the cause, we have to look at getting the knee back into shape. One injury I’ve been seeing more and more is meniscus injuries. For those who aren’t as street smart as I am in the ways of the knee, I’ll break it down for you. The meniscus is the cartilage discs in between your thigh bone (humerus) and shin bone (tibia), and act as shock absorbers, friction reducers, and kinetic springs for the knee joint.

Normally these little guys are pretty resiliant, but when you put a torque into the knee, like a sharp cutting movement, twisting, or lateral bending, the meniscus can take a beating and actually tear. As a result of the tear, there may be a flap of cartilage that gets stuck in the normal mechanics of the knee flexing and extending, and make the knee feel like its’ locking or giving way. Think of a time when you had a small cut that produced a flap of skin that got caught on everything. Anytime something caught it, it hurt like hell, and the only thing you could do was to cut off the excess. Well, most of the time, surgery is needed to trim back the flap, repair the tear, and make the meniscus work as best as possible. The downside is that the meniscus is very slow to heal and susceptible to reinjury, and the loss of any meniscus material just speeds up the process of developing osteoarthritis, which is as much fun as it sounds.

Normally these little guys are pretty resiliant, but when you put a torque into the knee, like a sharp cutting movement, twisting, or lateral bending, the meniscus can take a beating and actually tear. As a result of the tear, there may be a flap of cartilage that gets stuck in the normal mechanics of the knee flexing and extending, and make the knee feel like its’ locking or giving way. Think of a time when you had a small cut that produced a flap of skin that got caught on everything. Anytime something caught it, it hurt like hell, and the only thing you could do was to cut off the excess. Well, most of the time, surgery is needed to trim back the flap, repair the tear, and make the meniscus work as best as possible. The downside is that the meniscus is very slow to heal and susceptible to reinjury, and the loss of any meniscus material just speeds up the process of developing osteoarthritis, which is as much fun as it sounds.

Now the really fun thing is that when the knee gets injured, the first thing that typically happens is the nerve innervating the quads tends to shut down and reduce the amount of impulse it’s providing to them, making it sort of like a dimmer switch on low setting. The muscle becomes weaker, begins to atrophy, and creates a happy little muscle imbalance. The downside to all of this is that with the reduced internal stability of the knee from the injury, coupled with the reduced external stability from the quad de-activation, there is a very high likelihood of a re-injury or at least a reaggravation, which in istelf can be aggravating. Strengthening of the quad muscles has to occur to get the muscle imbalances reduced, while also providing some external stability.

But Dean!!! If I start loading a bunch of weight on the squat bar, won’t that cause some problems for a meniscus??

Yes, yes it will. Axial loading and impact are the enemy of the meniscus injury, so performing typical squats, lunges and deadlifts aren’t gonna work here, junior. On top of that, using a leg extension will just grind the hell out of the knee, make you look like a loser, and make your client want to spin-kick you in the face Chuck Norris-style.

The downside is that they can’t because their knee is pooched. Oooohh, the conundrum!!!!

So how do you get quad activation from adequate loading without adding axial weights and compression?? Enter the elastic resisted knee extension.

By tying an elastic above the knee and pushing back into it as shown in the video sequence below, the quads still have to work to extend the knee, but save the meniscus from compression by having a transverse force instead of an axial force.

Once this exercise becomes too easy, you can progress into body weight squats with a limited range of motion and then into full squats.

Let’s say you’re not injured and want to blast your quads even more? Well, the second progression is for you!!! By applying the transverse resistance during a one-legged squat, you get that much more quad for your dollar. To build leg strength with hip stability against internal rotation, we have variation numero three. This is a progression on Gray Cook’s neural reactive training, by performing it with a one leg squat instead of a lunge.

There’s lots of ways to increase loads on any given joint by simply changing the direction of force application, which is one of the best reasons to work out with elastics, tubing and cables systems. Of course, you can’t look nearly as badass using some tubing as you can lifting 5 plates aside.

In some cases, you can look like the worst trainer ever.

5 Responses to The Best exercises You Could Ever Do: Quad Activation Progressions