5 Things I’ve Been Wrong About and How I Updated my Thoughts on Them

One of the fun processes to moving is packing. And by fun I mean I want to take a rusty lawn rake and slowly exfoliate my eyeballs while listening to Justin Beiber sing a Tiny Tim song in falsetto. But during the process of packing and moving you tend to have to go through stuff to figure out if you want to keep it or toss it. In many instances, you find stuff you would rather have left forgotten and kept in a hidden box somewhere, or will simply get a memory and the thought of “what was I thinking” and a good chuckle.

Hey, there was a time when I had frosted tips in my hair. There was a time I had more hair and less five-head. For those who don’t know, that’s when the forehead is no longer a forehead and has grown a size.

But hey, everyone’s walked that line once in a while. Anyone who was over 15 years old during the 80’s likely has some questionable fashion sense and hair styles, so it’s not uncommon to change your minds on what looks good or how things work.

This updating process is something I feel is important to include with workouts as well. I remember a trainer I used to work with who would give everyone (repeat: EVERY SINGLE ONE) the exact same workout. Exercises, sets, reps, rest intervals, same, same, same. They left to go train in a different part of the world for about 5 years, then came back and still had everyone doing the exact same workouts, this time with new clients who didn’t know any better.

It’s great to keep working on the stuff that produces a benefit, but it’s also important to try to see if you can find something that works better. For instance, If I take a certain route to get to work, I can make it there in about 30 minutes, through pretty intense traffic. If I take a different way I can make it to work in about 25 minutes along multi-use trails with next to no traffic at all, so while I could stick to the heavy traffic route and not know any different, I could get better results with less likelihood of injury by taking the second way. That’s progress, yo.

Similarly, I look back on some of the programs I had clients and even myself go through back in the day and cringe a little. Not to say I was doing stupid stuff all the time, just some of the time. There was also a lot of stuff that didn’t show me any appreciable benefit or was somehow inferior to another way of training I’ve learned since then, and some stuff was just wasting time not doing anything but making a client breathe hard and sweat.

Because of this, I wanted to outline a couple of the big things I’ve switched my thinking about in the past few years, and also show what my newer thinking is in their regards. I’m sure I’ll change those down the road as well, but for now they seem to work.

#1: Instability Training

There was a time when I would have clients do a fair bit of labile surface training, or standing on one foot with different force vectors pushing or pulling on them. It was challenging, but in terms of getting them stronger or in better conditioning, it didn’t really do too much. By that I mean there was no measurable outcome that would show improvements in any dimension, other than balance. This is still an important consideration, especially if the person can’t stand on one foot on solid ground, but there’s definitely a point of diminishing returns when it comes to this stuff.

I mean, if you’re goal is to juggle chainsaws while slack lining across the grand canyon, go for it, but training for the Bosu Olympics won’t necessarily make you stronger than putting a barbell with a challenging weight in your hands and having you develop tension on solid ground. And in their marketing, claiming the balance tools train the “small stabilizer muscles” and that there isn’t any impact to the bigger muscles is like in the movie Blood Sport where JCVD had to break the bottom brick while leaving the top ones untouched. It’s not likely to happen.

There’s also considerably fewer falls and fear avoidance when it comes to the use of labile surfaces when you don’t use them, plus muscle contraction velocity, peak and average power, and co-contractile strength are all higher when on a stable footing, so there’s some limitations that would directly impact your training when using them.

#2: Not Everyone Should Deadlift

There was a point where I would try to have every client deadlift in some way or another. It’s a good intention, but in some cases misguided to think everyone should be able to do a movement. Now, I’ve regressed the movement consistently down to using a 5 lb dumbbell in a version of a sack lift off risers, but some people just couldn’t do that without pain.

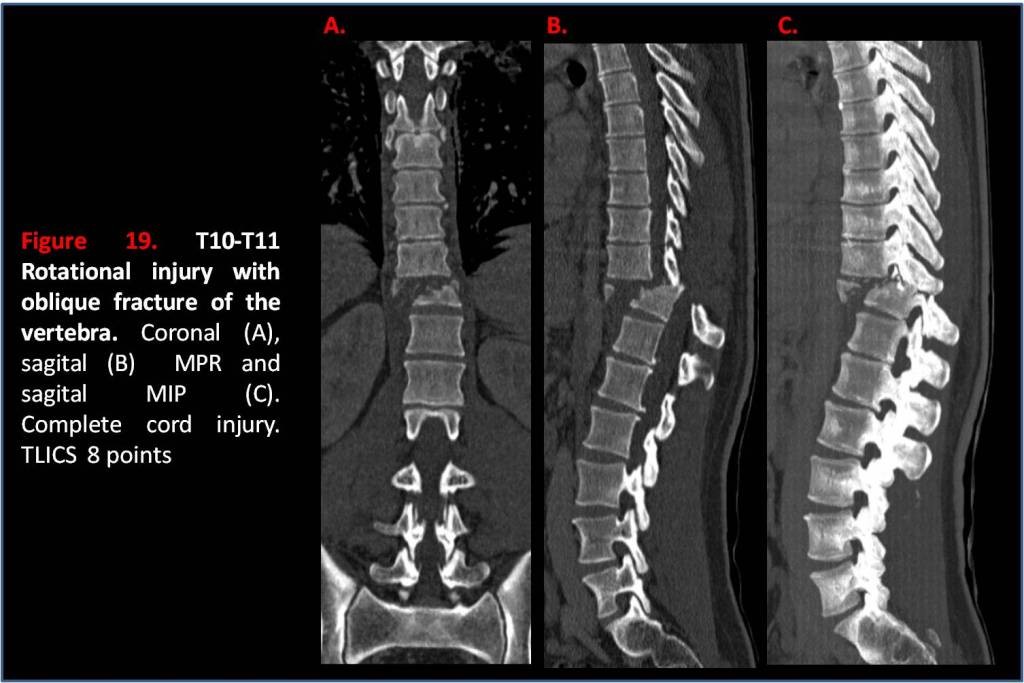

The thing about a deadlift is there’s more shear force on the spine at the bottom position than in most movements, and if the person has trouble controlling their spine in the presence of this shear, they’re going to have trouble with it. There’s also anatomical and physiological individual differences that could potentially limit an individuals’ ability to successfully lift stuff up and put it down.

This can commonly occur when someone has something like a pars fracture, spondylolisthesis, degenerative osteoarthritis, disc degneration, nerve irritation/compression, or even if they have some nerve entrapment coming through the sciatic arch.

So instead of focusing on using deadlifts, we can still train hip hinging with more of a transverse load instead of a saggital load. There’s also squat patterns that seem to be beneficial for a lot of people who can’t deadlift, and still allows them to see a training effect without pain or dysfunction.

The downside is usually you can’t tell who won’t respond well to deadlifts and who will until you actually do a few and see what happens. Some people the reaction will be immediate, in that they will say “this hurts my back,” whereas others won’t have any issues until they get out of bed the next morning, then say “those deadlifts hurt my back.” while immediate pain isn’t good, it’s a better feedback tool than delayed pain as you can adjust it pretty immediately, wheras day after pain sucks because it’s too late to adjust and you just have to recover. For those people, we can try a couple of times to see if it gets better or continues to make them hate my face, and if it gets better we just progress slowly. If it stay hating everything, we can regress and even remove without issue.

I’ve probably had about 8 clients in the last year or so who just couldn’t tolerate deadlifts. 1 of them came from surgical disc repair, and funny enough another client who had the same procedure from the same surgeon in the same month could deadlift his bodyweight within 6 months of surgery, whereas the other couldn’t tolerate an 8kg kettlebell. Everyone is different.

#3: You Probably Don’t Need More Mobility

For the majority of stuff you need to do in a days work and life, you likely have all the mobility you need. If you want to squat to the floor, get your arm into a layback position for throwing, or do some funky yoga contortionist stuff, you’d better hope you have the right structure for it.

As I’ve noted in the past, much of our mobility is going to be determined by joint structure. You can’t stretch bone into bone. If you try, you’re going to hurt. Period.

I didn’t always think this way. I used to believe many of a persons problems were because they needed more mobility. There was a time when I was stretching the hamstrings of a guy who had chronic low back pain and getting his foot almost behind his head. He said “Dean, do I really need to stretch more if I can get my foot this far back?” I didn’t really have a good answer that I could give, which meant I had to change how I thought.

Most injuries or performance limitations don’t come from a lack of joint range of motion, but more so from a lack of control through specific points in that range of motion. For example, let’s say a sprinter has repeated hamstring strains, can blast the doors off a 100 meter sprint and can deadlift a house. Odds are they don’t need to be able to touch their toes if their power is coming from the hamstrings contracting rapidly. But let’s say we have them do an end flexion contraction and they have 2 things happen:

- zero strength or control in that position, and

- Cramping like a mutha.

If the runner has stupid cramping in this little movement, the odds of them generating any power in their kick during sprinting is pretty minimal, and they’re likely to either overstride and reach, or they’re going to only develop tension through the initial half phase of their swing, which means they’re going to hit a brick wall at the end of their usable range. To go faster, they reach further forward instead of kick backward, and wind up tearing.

If they can touch their palms to the floor, not only do they not need more stretching, they’re probably also kind of slow. More stretching won’t make them explode off the ground and propel them down the track.

Stretching and mobility is fantastic when done properly, and while the body is controlling the range of motion it’s being put into. However, there’s often a disconnect in static or passive range of motion and active range of motion, or how much of that range you can actually use and do something with. In this instance, it doesn’t matter how much you have if you can’t access it. It’s like standing in front of an ATM and needing cash but only having $19 in your bank account.

Using stretching to either improve active range of motion, reduce pain or improve performance is unfortunately just scratching the surface of possibility, and would likely do more harm than good, or at bare minimum do very little at all.

#4: Higher Volume Plans only Benefit Beginners and Advanced Lifters

Beginners get a pass on anything, because they can simply walk by a weight room on a daily basis and see some kind of improvement. It’s prudent to start them off with less resistance and work on grooving a movement competency before loading weight on the bar.

For more experienced lifters looking for hypertrophy, it’s a good way of getting some gainz, based on some of the newer research coming out that shows hypertrophy improvements with 30+ rep sets. These undoubtedly suck to do, but oh well. If it works, shut up and do it.

For those who have been lifting for between 2-10 years and aren’t chasing maximum hypertrophy, it’s a good idea to have a few exercises that don’t go over 10 reps. Even for most non-accessory movements sub 5 rep sets would be a good idea. The main reason for this is to limit fatigue related breakdowns in technique and also to increase the stimulation of total-body adaptations to lifting, while also getting strong as fuark in the movement you’re training for. I won’t lie, there’s something satisfying about sliding more weight on the bar and tossing it around.

A sample breakdown for these intermediate lifters would be one or two power lifts of 3-5 reps, 5-6 sets, and then 4-6 accessory movements of either 10-15 or 20+ reps where they would want to see some hypertrophy or help out their power lifts, or simply work on areas they want to work on. Skill work would come first, meathead grinders coming last, and finishers when you want to not be able to feel your left arm any more.

Most power exercises will likely be trained in the saggital plane, which is fine, and many accessory movements would do well to train through non-saggital plane actions to help keep the body able to move through as much space as possible. Locking everything in to saggital will make someone strong as hell, but unlikely to carve up the dance floor, shoulder check, or even breathe while laying on their back.

Another caveat for the higher volume programs come for the rehab based plans where the person needs to build endurance but can’t tolerate the tissue strain from heavier loading. Instead of doing 30 rep sets, I would instead opt to do repeated 5-10 rep sets with a bit of resistance to give some rest time between sets and allow for a greater deformation capability, plus keep their strain loading limited, but that’s just me.

#5: The More Medical Limitations They Have, The More Cardio and Less Strength They Should Do.

While strength training is awesome, it does create systemic stress in people and while that stress is good and something to encourage adaptation, if someone has one or more medical complications, the stress level can be higher than they can manage effectively. This goes for anything from diabetes to heart conditions to endocrine dysfunctions. Essentially, cardio plays a huge beneficial role in almost any medical condition management, and strength training should take a back seat to it.

I would even say that as beginners, or even overweight clients, their initial impetus should be to include cardio based exercise above strength training. The main benefits for this is that circulatory health will help drive strength gains down the road, whereas strength gains may not have any appreciable benefits to circulatory health and function, especially if the individual isn’t hitting a caloric threshold from their exercise plan to see adaptive responses.

Many in the fitness community will deride cardio, calling it useless for fat loss, which may or may not be true depending on its application and nutritional status of the individual, but it can’t overshadow the health benefits of having a responsive cardiovascular system to improving health and also performance.

There’s lots of apps out there that can help track activity, and if you want to spend more money you can get heart rate monitors that track everything from calories burned to steps tacken, to biometric information that could be useless to most, but essentially, including some form of cardio is fantastic for most medical clients and beginners, and should be a main focus above strength training.

I used to have clients train with me 3 times a week and see minimal improvements in their numbers, depending on what their condition required measuring. I dropped many of them down to once a week and supplemented it with more steady state cardio for 20-40 minutes per session, depending on the person, and saw better improvements in their numbers. Me working with them less had a better effect than me working with them more, as long as they did their cardio.

So, there’s 5 things I’ve changed my mind about in the past few years. I’m sure I could do a lot more than this, but I want to keep up the facade that I know something here or there and I’m not just a total dullard.

15 Responses to 5 Things I’ve Been Wrong About and How I Updated my Thoughts on Them