3 Fitness Myths and Preconceptions Destroyed

So I was teaching a course this weekend on Post-Rehab for Personal Trainers, and wound up getting into some good heated discussions about a few of the big points I was raising with everyone. A few of the trainers in the class thought I was off my rocker, until I was able to show them why, from a biomechanical, adaptive and research-backed perspective, my thought process held up against the conventional wisdom. Here’s a sample of some of the questions I was asked:

Why do you say overhead pressing is bad for your shoulders? I do it all the time and nothing’s happened!!

How can my abs look so strong and be so unstable, and what does that mean to my back??

Why are you teaching without your shirt on again, and how did you get your arms so big?

Okay, maybe I made that last one up, but still, they are impressive.

So today I want to go through the top three argument starters that brought up some ire in the class. Trust me, this will be both fun, and annoying if you still hold any of these preconceptions as true.

Misconception #1: Pressing Movements Matter

For the Average Johnny Benchpress out there who will bang out 30 sets and then wonder why their shoulder hurts, this is going to come like a slap in the face. The argument is that pressing is a functional movement that needs to be trained in order to keep the body strong and stable.

Agreed.

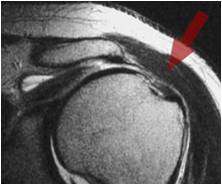

But here’s the kicker. Pressing will only make you strong at pressing, not stronger overall. The pressing movement, specifically bench press, puts your humerus into an internally rotated position, with abduction and horizontal flexion, which is the movement pattern that causes the greatest amount of compression on the subacromial space that leads to rotator cuff issues. This is also commonly called impingement, sub-acromial bursitis, whatever. The main point is that the shoulder will hurt. Additionally, the humerus begins to sit in the glenoid fossa somewhat differently (typically in anteversion, or forward in the glenoid instead of centered nicely), which alters the mechanics of the rotation of the humerus and can lead to issues down the road.

Add this to the fact that Sher et al (1995) took MRIs of asymptomatic subjects, found rotator cuff tears in 34%, and up to 54% in the sub-population older than 60 years, and we have a situation where weaker and possibly damaged rotator cuffs are now being led to the slaughter because we believe how much ya bench is a valid question.

Even worse than bench press is overhead press. Easy there, Cross-fitters. Pull down the compression tights for a minute and listen up.

Let’s look at the common posture of most people out there, which is unfortunately a slouchy version of kyphosis. The first thing to think about kyphosis is that it alters how your shoulder-blade can rotate and glide along your rib cage. Don’t believe me? Slouch like it’s going out of style, then try to raise your hands over your head. Didn’t work, did it? Now sit up tall and strong, and bring your arms over head. My guess is that you managed to get them a lot higher. You’re welcome.

So we have an altered posture that limits out ability to move our arms and get them overhead. On top of that, we also tend to have a forward head posture, which alters the mechanics of the cervical spine. The shoulders pretty much hang off the C-spine, which means it has to work absolutely flawlessly to support the weight overhead, especially since we already know the mechanics of the T-spine are probably less than ideal.

Now not to say that this is the case in everyone, but the vast majority of people exhibit these movement impairments. On top of that, we have coaches saying to jut your neck forward to stabilize the shoulder because people have less than ideal mechanics. Let’s be honest here, who looks like they’re doing the movement better and is going to lift a hell of a lot more weight without blowing out their sphincter…

This, or this?

What’s the solution? Pulling. It’s always funny to hear someone say they can bench press 300 pounds at 190 pounds body weight, but can’t perform a single bodyweight pull up. If we think about strength ratios, that works out to a roughly 3:2 ratio of pressing to pulling, where the two should be closer to 1:1, which means that 190 pounder should be able to do a chin up with 100 pounds strapped to their build. With sore shoulders, it should probably be closer to 2:3 pressing to pulling.

Pulling helps to work as a synergist to the rotator cuff function of pulling the humerus into and down in the glenoid fossa, which helps to increase the stability of the shoulder. It also forces the T-spine to move through extension, and gets the shoulder blade to retract and depress, a position where it has the best chance of being solid against any forces imparted on it.

The thought that pressing is important for sports is without a doubt, however I think the common thought process of how to train pressing is somewhat detrimental. Living in a winter city, I’m used to pushing a few cars out of snowbanks, and I can assure you, my legs were usually working waaaay harder with each push than my triceps or anterior deltoids.

Most athletic movements involve the entire body, with the legs driving the weight and the arms guiding it.Which means using a bench press is a segmented version of a pressing movement that takes out the drivers, and overhead pressing, with the exception of a jerk press, do the same, and in a more injury-prone position.

Misconception #2: Knee Pain is From Knee Issues

This was a big head-scratcher for a lot of people, because they think “well the knee is sore so I should do stuff to the knee to make it better.”

In any case except acute trauma, this isn’t actually the case, as the knee tends to follow what the hip and foot tell it to do. This is one reason why myself and a lot of others call the knee a “stupid joint,” because it won’t think for itself!

Lets say you’re one of the many many people with weak bums. This makes your knees have to do more of the work in triple extension when performing squats, lunges, stepups, etc, which makes the knees have to take more force, and eventually leads to some sort of ouchie. Likewise, let’s say you have some restriction in your ankle to go through dorsiflexion, where your knee goes over your toes. If your ankle doesn’t move well, the knee has to pick up the slack to perform the movement. Again, too much of anything isn’t a good thing, unless it’s a bikini tan judging contest, in which case the more the merrier!!

What does all this mean? Instead of focusing on simply knee-dominant exercises like squats and lunges, the achy knee should focus on hip-dominant exercises as well as ankle and hip mobilizing exercises.

By getting the hip and ankle to work properly and produce strength, the knee will usually take care of itself.

Misconception #3: Core Stability is All About the Abs

Saying that core stability is all about the abs is like saying that Luongo is the only reason the Canucks are going to win the Stanley Cup this week (There’s also two Sedins and a guy named Kessler). Core stability involves co-contraction of not only the abs, but also the erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, pelvic floor, diaphragm, as well as the pelvic and thoracic stabilizing muscles.

The term stability in this instance essentially means “resistance to change,” which means that if you’re doing something with your arms or legs (or both, whatever floats you’re boat), the core is contracting to resist spinal flexion, extension or rotation. Essentially, the core works as an anti-movement zone to transfer power from the lower body to the upper body and vice versa.

So true core stability has very little to do with the rectus abdominis itself, and more to do with a global sense of stability through the lumbar spine into the pelvis and thoracic spine. This is why when someone asks whether an exercise targets the obliques it makes me want to throw my face into an axe.

So hopefully your worlds are still intact and your minds haven’t been blown completely after reading this, and that I didn’t piss you off as much as a few of the trainers in my class this past week. I’m more than willing to debate these thoughts, so feel free to comment on them below. Just remember, I will always win an argument, so bring your “A” game!

![doyle_overhead_squat[1]](https://deansomerset.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/doyle_overhead_squat1.jpg)

13 Responses to 3 Fitness Myths and Preconceptions Destroyed