Overhead Motions in Hockey Players: Should You Even Go There?

I’ve had the fortune to work with a bunch of hockey players of different levels through my career: many in one-on-one scenarios, a few junior teams and even a chance to assess a pro team. It’s a unique sport where much of the game is played in a hunched over position, they ride around on knives and use a stick to push a puck of rubber across the ice they’re riding their knives on, all while hitting each other and pushing the puck across a line guarded by a heavily armoured gladiator, who at one point in time didn’t wear a mask or even much padding at all.

Plus, every now and then a couple guys decide to punch each other.

Because of the uniqueness of the sport, there’s also some unique adaptations a lot of the players have to deal with as a result of playing their sport, and in some ways you could consider those adaptations to be necessary to excel at their sport.

Ankle mobility tends to be limited as they spend most of their time in solid formed skates where ankles tend to not move much at all.

Glutes tend to be very strong as this is the major propulsive muscle and movement of the skating stride. Associated with this is a high incidence of groin pulls.

Shoulder mobility tends to be very limited, especially in overhead motion. With the stick on the ice, players rarely bring their arms over their head, meaning that movement is rarely used.

Looking at shoulders, they’re a particularly vulnerable joint for injury, especially for the demands of the sport. Looking at the incidence of injury, Touminen et al showed that in 10 years of World Junior ice hockey championships, the shoulder was the most injured joint of the body, second only in absolute injuries to lacerations with 2.0 injuries to the shoulder per 1000 games played by all athletes. In a separate study, the same authors showed injury rates among female players was somewhat different, with upper body injuries resulting in 1.4 upper body injuries per 1000 games. MacCormick et al compared all research on hockey injury rates between men and women and found that men had a much higher rate of shoulder injuries than women, and attributed it to the increased contact involved in checking, which isn’t present in many if not all women’s divisions.

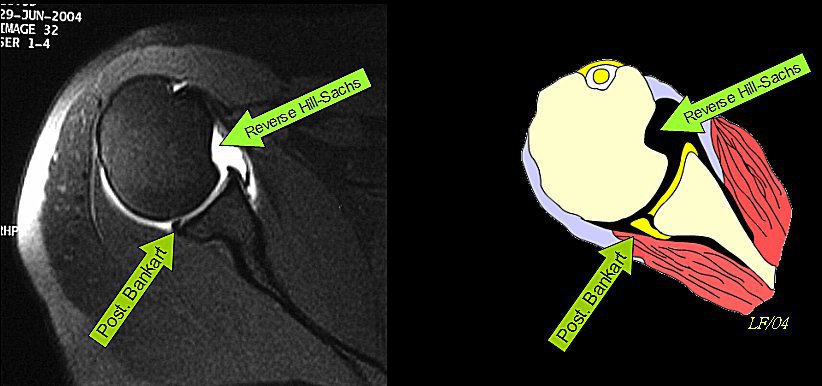

Dwyer et al showed that the two most common shoulder injuries hockey players have based on MRI results are bankart lesions, an anterior inferior labral tear, and a hills sach lesion, a cortical depression on the posterior humeral head. Essentially, these two injuries only really develop via slipping of the humerus in the glenoid fossa and significant reductions in stability of the shoulder.

Anecdotally, in the players I’ve worked with who have seen significant ice time, they all seem to have bilateral AC joint separations that have either calcified over or are mildly springy. This is typically an injury that occurs with lateral impact to the shoulder, which is essentially the entire mechanism of being checked into the boards by an opponent.

Some estimates put AC joint injuries at 40-50% of all shoulder injuries among contact sports, putting it at odds for the bankart and hills sachs lesions, but meaning shoulder injuries of any type are still a significant source of concern for coaches and trainers who work with hockey players.

Now interestingly, these changes can be seen bilaterally, but the sport itself tends to produce a lot of unilateral asymmetries in terms of structural and neurological adaptations, depending on which hand the athlete is dominant with. Kevin Neeld did a fantastic write up on these asymmetries and it is definitely something everyone should read if they work with hockey players.

Sean Skahan, a strength coach with a number of NHL teams, talked about his use of the FMS screen to identify issues and asymmetries that commonly occurred with his athletes, which included notable thoracic kyphosis and restricted shoulder mobility, especially in their new players either through draft or trade. I’m sure he’s updated his screening and corrective process since this was written in 2011, but the concepts are still consistently occurring.

Hockey players tend to have limited shoulder mobility in overhead movement, and also little sport specific need to keep or regain that movement to improve performance in their sport. Considering if a player raises their arms with their stick to a position above their shoulders it’s a high sticking penalty, likely 99% of game time is played with the arms below 90 degrees of flexion.

One time where the arm may wind up over the head is on the backswing of a slap shot, but the specific position of this movement is more of a lateral shoulder flexion than anterior shoulder flexion, meaning it’s a movement that more resembles a dumbbell fly than an overhead raise.

In addition to this, many hockey players tend to exist in a very high tension manner, essentially flexing all the time to protect against hits and stay sharp. Because hockey is such a high output sport with fast shifts and quick recovery, stimulant use is very common, which tends to make muscles more fired up, but also considerably more tensed and tight when taken over the span of a couple of years. These stimulants are commonly just energy drinks like Monster or Red Bull, but could also be more powerful. It’s worth noting this isn’t all hockey players, but a trend has emerged with a lot of players.

So we have a combination of factors that all feed into reduced shoulder mobility for overhead movement:

- reduced thoracic extension mobility

- reduced AC joint mobility

- potential bankart or hills sachs lesions

- high incidence of head and neck injuries, which directly affects shoulder motion

- high sympathetic activity

- chronic pattern of flexion postures, limited overhead movement, and padding to resist overhead movement. The only time players arms go overhead is during goal celebrations

So because of these factors, we have to ask the question: Is a reduction in shoulder motion a positive adaptation to help improve the stability of the shoulder to handle the contact of the game, or is it a negative adaptation that hurts the athlete long term?

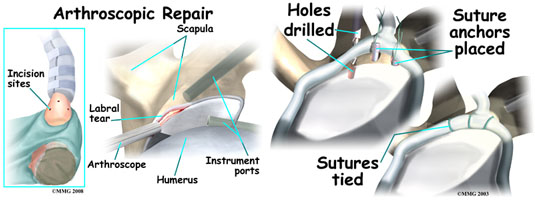

A lot could be said for the benefits of reduced mobility and increased stiffness of the shoulder in terms of improving stability and reducing the likelihood of instability injuries. In many instances once hockey players have surgical repair to torn labrums or shoulder separations, the mobility of the shoulder is significantly reduced, and the shoulder becomes considerably more stable, with the athlete not having further problems in the area in many cases. If a more conservative treatment is taken where the shoulder isn’t repaired as”tightly” the athlete tends to have recurring issues at a higher frequency. This is purely anecdotal based on working with about 20 athletes with various shoulder surgery procedures and gauging their outcomes. I could very well be wrong in this assessment.

Another component that tends to lead into incidence of re-injury is when in the season the injury occurs. If the shoulder is injured at the start of a season and the team tries to get the athlete back on the ice before the end of the season, rehab is commonly rushed, whereas if the injury occurs in the later stages of the season, there’s considerably more time to recover before the athlete has to compete again at the beginning of the following season, meaning instead of a 6-12 week recovery, they have the ability to have an 18-24 week recovery, allowing much more healing and strength & stability recovery before testing with impact again.

So we know that a lot of hockey players have a lot of things holding their overhead mobility back, and may not ever have the structure to get overhead without compensations if they’ve had an aggressive repair to a structural injury. Should they involve overhead exercises?

I would say no, if the exercises are loaded, such as military press or full hang or kipping pullups. If they don’t have the ability to get to a full overhead position without load, adding load or velocity won’t be beneficial at all. The benefit to movements like a back squat or even front squat may be minimal if they can’t get the shoulder mobility to get into position or if their AC joints are too tender to have the bar resting on them, which means straight bar variations may have to be nixed in favour of GCB bars, safety squat bars, or Buffalo bars.

Should shoulder mobility work be incorporated? Absolutely, but it’s going to need to be adjusted to the individuals’ ability, and take into account all of the factors that lead into shoulder mobility:

Breathing mechanics –> thoracic mobility –> scapular mobility –> glenohumeral mobility –> elbow & wrist mobility.

Starting with shoulder mobility before addressing the other prerequisites is like trying to learn how to drift in a car before you take it out of park.

So a simple outline to address shoulder mobility in hockey players could be something like the following:

- soft tissue work to reduce resting neural tone

- breathing work to help pump the mechanical system driving thoracic motion and reduce tone further

- thoracic mobility into extension with control to not hinge from the low back.

- scapular motion working on retraction and depression specifically, as well as upward rotation

- glenohumeral motion through internal and external rotation in varying positions of anterior flexion

- Any further elbow & wrist work that needs addressing.

This series would look something like this:

For strength work, pressing isn’t a direct problem, as long as most of it is not directly overhead. Most landmine presses, even bench press variations are okay, and football bar presses would be even better, and cable presses would be fantastic. Horizontal pulling, and slightly less than full vertical pulling would be awesome. One thing to watch for is to limit anterior humeral glide during any press or pull movement.

For long-term health, working on maintaining mobility is definitely important, but there’s always a cost of doing business. A more mobile shoulder may also be a more unstable shoulder, and might not be able to manage the impact of the game as well as a tighter shoulder. This isn’t an absolute, but it’s something to consider when working on creating absolute range of motion or active range of motion. As long as the athlete can achieve that range and control it, it should be maintained. If they’re significantly reduced because of previous injury, surgery, or structural limitations, their personal limits have to be respected.